In order to conceptualize materials used in pair-work activities from a sociomaterialist perspective, this study examined the moment-by-moment unfolding of 67 pair-work interactions in beginner- level Japanese-as-a-foreign-language classrooms. The types of pair-work materials used in the focal classrooms—either textbook or teacher-designed activities—were highly controlled with specific sequences of turns that learners were expected to follow. My analysis revealed that each phase of pair work—opening, main, and closing—entailed 2 concurrent layers of orientation to the ongoing event, namely, a ‘pedagogical-activity layer’ and ‘normative-interaction layer.’ The pedagogical-activity layer, in which students followed the prescribed turns, was constructed as private and individualistic, whereas the normative-interaction layer, in which students used normal interactional procedures, point to its collaborative, contingent, and remedial or corrective nature. The examination of pair-work cases with these layers helps us better understand the intricacy and subtlety involved in the use of learning materials, as well as the conflicting capabilities of the materials, pointing to a sociomaterial concept of human and nonhuman intra-action. This article also discusses implications for task design, as well as for the theorization of task in second language acquisition research.

Keywords: pair work; conversation analysis (CA); task-in-process; Japanese; intra-action

IN CURRENT LANGUAGE PEDAGOGY, PAIR work has been frequently exploited as a popular mode of instructional activity (Sato & Ballinger, 2016; Storch & Aldosari, 2013). In pair work, learners are assigned to engage with some kind of problem, or ‘task,’ with specific procedures and goals in hand (Breen, 1987). Instructional materials inscribed with the procedures and goals of activities, such as handouts, textbooks, PowerPoint slides, and whiteboard writing, are of- ten presented to learners, who then make use of such materials to accomplish the set objectives of the lesson. In many cases, learners are expected to initiate, carry on, and bring to closure task-induced interaction without the direct presence of teachers. This mode of inter- action, compared with the teacher-fronted for- mat, gives learners more flexibility and options, with each participant constructing unique, and of- ten unintended, activities (e.g., Coughlan & Duff, 1994; Mori, 2002; Roebuck, 2000). In beginner-level language classes, we often see activities that are highly structured and controlled by design so that learners maintain their focus on certain pedagogical targets—such as new vocabulary, grammar, or formulaic expressions—rather than being thrown into uncontrolled free conversations, which would likely pose challenges to many beginner learners with few linguistic resources available to them. Accordingly, writ- ten prompts used for pair work at this level also tend to be highly structured and controlled by specific content and the expected sequence of turns. As such, this pedagogical setup raises several important empirical questions for the investigation of learning as mediated by instruc- tional materials:

RQ1. What recognizable practices structure learner participation in pair work?

RQ2. What orientations do the learners dis- play in such practices?

RQ3. What roles do activity prompts play in pair work?

Unlike ordinary conversations where there is no external ‘control’ wielded over participants, the presence of physical materials that prescribe sequences of turns would inevitably alter the ways in which learners organize their participation in interaction. Altered participation, then, will shed light on different kinds of learning opportunities generated and made available for the learners.

This study sets out to answer these questions by investigating how pair-work materials are actually used by learners in beginner-level Japanese-as-a- foreign-language (JFL) classrooms. Through the examination of 67 pair-work cases, I discuss both convergent and divergent learner orientations to interaction and explain various roles played by pair-work materials. Based on the microanalysis of pair-work interaction, I conceptualize materials and materials use from a sociomaterialist perspective (Fenwick, 2015 Fenwick, Edwards, & Sawchuk, 2011; Guerrettaz, Engman, & Matsumoto, 2021, this issue). My collection of pair-work cases—with highly controlled and structured activity prompts—provide aspects of instructional context frequently found in the beginner-level language classroom. I argue that such activity prompts generate two overlaying learner orientations to the ongoing event, namely, ‘pedagogical-activity layer’ and ‘normative- interaction layer,’ which are concurrently present and oriented to while learners grapple with the semiscripted sequences of turns. These two layers intricately surface in various phases of pair work through participants’ verbal and nonverbal or nonvocal conduct vis-à-vis materials. The goal of this article, hence, is to delineate the complex and subtle picture of pair work, involving stu- dents, teachers and task designers, materials, and so on.

BACKGROUND

Pair work is a mode of instructional activity that is frequently used in many language class- rooms. In second language acquisition (SLA) literature, pair work is often associated with the concept of ‘task’ (Richards & Rodgers, 2001). The utility of task has been investigated enthusiastically by cognitively oriented SLA researchers (e.g., Doughty & Williams, 1998; Ellis, 2000, 2003, 2006; Long & Crookes, 1992; Pica, Kanagy, & Falodun, 1993), all of whom have endorsed task-based language teaching (TBLT) as a researched pedagogy (Samuda, van den Branden, & Bygate, 2018). While TBLT has been well received by practitioners as well (Ellis, 2018), the concept of task has been discussed diversely among researchers and practitioners in various contexts, which has resulted in a confusion of definitions, as well as controversies and disagreements over the construct (van den Branden, 2006). For example, Breen (1987) defined task as “any structural language leaning endeavor which has a particular objective, appropriate content, a specified working procedure, and a range of outcomes for those who undertake the task” (p. 23). Nunan (1989) endorsed a narrower definition: “a piece of classroom work which involves learners in comprehending, manipulating, producing, or interacting in the tar- get language while their attention is principally focused on meaning rather than form” (p. 10). For Ellis (2003), the label of task should be reserved for a meaning-oriented type, which should be contrasted with an exercise that has a focus on linguistic forms. In these narrower definitions, a clear contrast was drawn between meaning-focused and form-focused activities, to which learners’ attentions are directed.

These contrastive views of task are not sim- ply the problem of labeling, but they also reflect different epistemological standpoints. For example, borrowing Breen’s (1987, 1989) conceptual distinction of task-as-workplan and task- in-process, Seedhouse (2005) discussed how task- as-workplan, conceptualized as the pedagogical blueprint created by the teacher or task designer, is never identical to how task-in-process—viewed as participants’ actual operationalizing of the blueprint—is done in peer interaction. In other words, the teacher’s control embedded in a task- as-workplan does not necessarily transmit to actual learner operations during task-in-process. Essentially, task-as-workplan subsumes orderly and predictable learner actions, while task-in-process entails disorderliness and unpredictability as well. Indeed, a sizable body of previous research has shown how task-as-workplan is variously interpreted and performed by students according to circumstantial contingencies, including students’ learning histories and interpersonal relationships (e.g., Bannink, 2002; Coughlan & Duff, 1994; Hasegawa, 2010, 2018; Kumaravadivelu, 1991; Mori, 2002; Roebuck, 2000). For Seedhouse, it is task-in-process that needs to be highlighted in pedagogy in order to understand the actual learn- ing process. For Ellis (2000, 2003), in contrast, task should be characterized from the designers’ perspectives because “one of the goals of task- based research is to establish whether the predictions made by designers are actually borne out” (Ellis, 2003, p. 5). The differences in view are apparently tied to their epistemological standings (e.g., social constructionism, essentialism), and as such, it is perhaps unreasonable to determine the conceptual primacy between task-as-workplan and task-in-process. Fundamentally, my stance aligns with the viewpoints of Seedhouse and Breen in placing emphasis on task-in-process. I believe that our focus should be primarily directed at how task-in-process is constructed vis-à-vis various elements of the surrounding context, which include physical materials that they make use of, their co- present partners, and even their shared histories. This view also accords with the epistemological lineage of sociomaterialism (Fenwick, 2015; Fen- wick et al., 2011), which underscores the exami- nation of “the constitutive entanglement of the social and the material in everyday life” (Orlikowski, 2007, p. 1,435).

TBLT is often contrasted with the traditional instructional strategy called the present–practice– produce (PPP) model (Ellis & Shintani, 2014). The pedagogical context of this study (i.e., beginner-level JFL classes) is also recognized as having close affinity with the PPP model (Fujita, 1997; Hasegawa, 2018; Mori, 2005; Ohta, 2001). Therefore, when pair work is assigned to students in the practice or production phase of PPP-based lessons, targets of pair work—in terms of focal expressions, pragmatic functions, or interactional sequences—are normally known to students. As such, pair work is used asa means to practice and produce those discrete targets in a supposedly interactive format. Specific goals of pair work are also communicated through physical materials, which lay out some procedural elements, such as scenarios and roles of interaction (e.g., roleplay), questions (e.g., Q&A), pictorial cues (e.g., information gap), and linguistic cues (e.g., controlled conversation, model dialogue). On the one hand, such activity prompts are expected to exert control over learner behavior in their use of specific linguistic forms, communicative functions, or specific turn types that the teacher chooses. In this respect, activity prompts may be seen as the physical manifestation of task-as-workplan. On the other hand, as we will see in this article, these physical artifacts can also be treated variously by learners, leading to distinct patterns of participatory configurations.

The pair-work materials used in this study were highly controlled with semiscripted sequences of turns laid out for the learners to follow. Some turns were completely written out while other turns were bracketed to be filled with learners’ own utterances. Some cues were provided in words while others were shown in pictorial or visual forms. As such, the degrees of prescriptiveness and ‘incompleteness’ (cf. Hazel & Mortensen, 2019) were various. This arrangement was aimed at eliciting focal grammar items in a pedagogically efficient manner and in a conversation-like format. Although this description may give an impression of nonauthentic, old- fashioned, and drill-like design, in my own estimation, this type of prompt is found ubiquitously in commercially available beginner-level textbooks for various languages.

In fact, Hazel and Mortensen (2019) discussed a similar type of materials use in their study of ‘designedly incomplete objects.’ They examined how inscribed objects (e.g., handouts, whiteboards) with a section of text left blank or incomplete, combined with various interactional resources, were used to elicit particular types of contributions from the learners. Their conception of designedly incomplete objects was motivated by Koshik’s (2002) research on ‘designedly incomplete utterances.’ Koshik discussed how teachers elicited error corrections from students by marking their utterances as incomplete, thus inviting students to display their knowledge. Apparently, ‘incompleteness’ designed by teachers—orally in talk or written on objects—can be regarded as a common instructional strategy to facilitate learner involvement. Similarly, the pair-work prompts I analyze in this article have incomplete elements that learners are expected to fill in when they engage in pair work. In this study, I discuss how such incompleteness is oriented to by learners and the kinds of roles that pair-work materials serve or do not serve in this instructional context.

THE STUDY

The analyses of pair-work cases presented in this article are drawn from a larger project (Hasegawa, 2010). In that project, I employed conversation analysis (CA) as a main framework and closely examined 67 cases of pair-work activities that were video-recorded in second-semester Japanese language classrooms at a North American university. The main goal of the original project was to illustrate how learner practices, orientations, and resources demonstrated various aspects of task-in-process in the focal classrooms. In particular, I wanted to examine how learners organized their participation through activity prompts made available for them. In this article, I present cases that are particularly illuminative of materials use and discuss how various roles of activity prompts emerge in this instructional context and what implications can be drawn for materials design through the lens of sociomaterialism. I will draw particularly on the sociomaterial notion of ‘intra-action’ (Barad, 2007), conceptualized as the emerging entanglements of “heterogeneous elements of nature, technologies, humanity and materials of all kinds” (Fenwick, 2015, p. 87). Intra-action subsumes the holistic and complex nature of human and nonhuman relations. From the sociomaterialist perspective, this study aims to illuminate the intricacy and subtlety involved in the use of learning materials.

Data

Six different sections of the same course were involved in this research. These classes, taught by graduate teaching assistants, shared the same syllabus and lesson schedule, as well as the overall pedagogical approach based on proficiency-oriented teaching (Hadley, 2001). The second volume of the textbook series, Genki (Banno et al., 1999), was used as the main course material. This widely used JFL textbook is primarily organized around a grammar syllabus with some additional layers of topics and functions. Thus, typical lessons focused on a presentation of discrete grammar points and vocabulary, followed by practice of those items, sequenced from con- trolled to less controlled. As such, it is plausible to regard these lessons as employing the PPP model. Pair-work activities were assigned after the introduction of new grammar and vocabulary items. Before each session of pair work, activity prompts were introduced in a teacher- fronted format, and one or two items on the prompt were practiced together. After each pair- work activity, the whole class was called back, and a post-pair-work answer-check session usually ensued.

The researcher video-recorded the entire class session from the beginning to the end, including the teacher-fronted interaction. At least one— and often more than one—pair-work activity was assigned in each class session. I video-recorded pairs of learners who gave consent in advance to capture procedural details of their pair-work interaction. A wireless microphone was placed between the students in order to secure the quality of audio, but the camera was placed remotely so that their interaction would be minimally affected by the presence of the camera. The total number of pair-work cases video-recorded was 160, carried out by 59 students. Of these cases, 67 cases that made use of written activity prompts were chosen to constitute the database for the present study. These prompts were based on the textbook or created by the teachers, and they were usu- ally shown on the front screen by an overhead projector.

Analytical Procedure

The video-recorded interactions were transcribed, using the Jeffersonian transcription system (Jefferson, 2004; see the Appendix). Japanese utterances were captioned by approximate English translations beneath the original utterances. All translations were done by the researcher, who is fluent in both Japanese and English. Glosses for grammatical terms were explained in the main text whenever appropriate but not included in the transcripts in order to keep the readability of the transcripts. In addition, screenshot images from the videos are shown to illuminate the bodily conduct pertaining to the present analysis.

In the original project (Hasegawa, 2010), I employed CA as the main analytical framework. As an offspring of ethnomethodology, CA is known to be agnostic to exogenous theories beyond what is observable in the data because its epistemology lies in ‘members’ methods’ (Garfinkel, 1967) rather than abstract concepts conceived by theorists. Such a strictly data-driven, participant-relevant approach adds tremendous insights to our understanding of task-induced interaction, but it may also limit its interpretive scope. For the current purpose, I believe that the sociomaterialist perspective will further enhance our understanding of materials and materials use. In particular, while CA excels at the investigation of microconduct in interaction, sociomaterialism is committed to a holistic understanding of social and material intra-actions (Barad, 2007), which may encompass micro, meso, and macro levels (Fenwick, 2015; Fenwick et al., 2011). As such, sociomaterialism brings in broader implications to the findings of CA analyses. I would like to reinterpret and recapitulate the original CA analyses from the project in the light of task design and learning opportunities (i.e., participation in instructional activities).

OVERALL PARTICIPATORY CONFIGURATIONS OF PAIR WORK

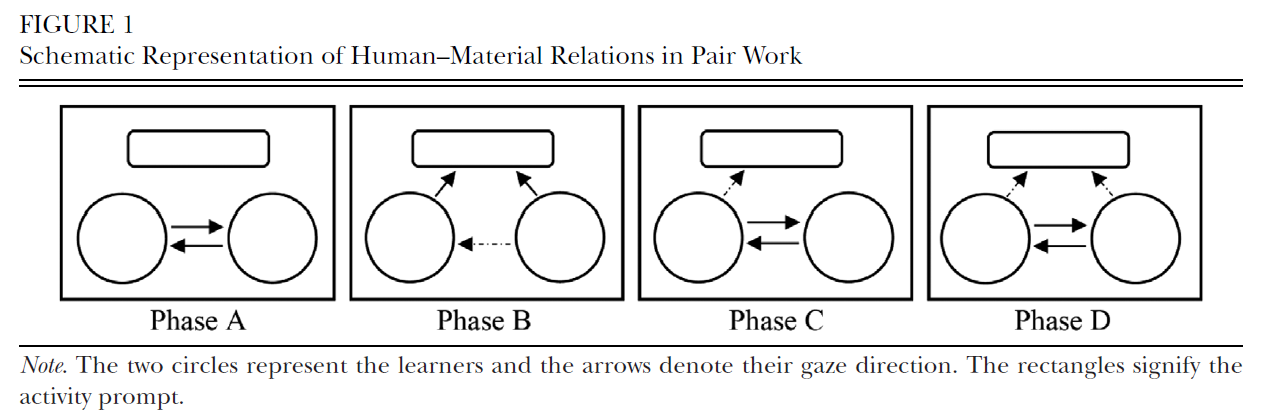

In scrutinizing the database, a noticeable pattern of participatory configurations (cf. Goffman, 1981) was observed among learners and activity prompts. Changes in participation were signaled largely by bodily postures and gaze directions (e.g., Goodwin, 2000), and they corresponded to the distinctive phases of pair work (cf. Hellermann, 2008) and the particular actions that learners were undertaking. Figure 1 illustrates this pattern schematically. The two circles in each phase indicate the learners who are engaged in pair work while the rectangles above those circles signify the activity prompt being made use of. These prompts may be located at the front of the classroom, where transparency sheets are displayed, or located in front of each person when textbook activities are used. The arrows denote gaze directions of each learner, showing different configurations. In short, these diagrams represent the social (i.e., learners) and material (i.e., activity prompts, textbooks, overhead transparencies) elements of pair work.

A typical pair-work session proceeds from Phase A to Phase D. Phase A is observed at the opening, where learners mark an activity boundary from teacher-fronted interaction to peer interaction and negotiate the first-turn allocation (cf. Hellermann, 2008). The learners look at each other and establish a mutual orientation to initiate a pair-work session. Although this phase shows a co-constructive and interactive aspect of the occasion through mutual gaze, it does not mean that pair-work prompts do not have any place here. As we will see in the next section, the intra-action of human–materials elements is already emergent in this phase.

In Phase B, the learners—usually both of them but occasionally only a single speaker— look at the prompt as they try to retrieve in- formation. When the speaker signals some kind of production trouble through speech perturbations (e.g., silence, sound stretch, hesitation marker), or in the case that some unexpected event may arise (e.g., nonunderstanding, laughter), the other learner—the hearer—shifts their gaze toward the speaker in anticipation of a potential intervention or assistance. This phase is concerned with the completion of the prescribed sequence of turns. Their gaze is largely directed at the prompt, but there is also constant attention to each other’s conduct, maintaining some degree of co-orientation and interactivity of the occasion.

When production trouble becomes visible in interaction, Phase C is occasioned. This phase is regarded as fully interactive as learners try solving the trouble collaboratively through various re-medial or corrective activities, such as repair and word search. The speaker may keep their eyes on the prompt, or they may look at their partner in the hope of soliciting help. Most likely, the hearer of the trouble continues gazing at the speaker. Troubles are usually shared between the learners, who jointly engage in solving them.

When the solution is reached, the learners resume Phase B or transition to Phase D, depending on the specific design features of the prompt. That is, when the turns with a large part of the utterance left blank or to be completed by learners, such as ‘follow-up’ or ‘comments,’ are present, the recipient of such turns tends to show orientation to the speaker, as is often seen in ordinary conversations. Yet, if the turns involve less of such incompleteness, the learners resume Phase B as they need to retrieve information from the prompt. The final turn tends to be a sequence-closing third (Schegloff, 2007), that is, an additional turn after an adjacency pair (e.g., question–answer), such as acknowledgment and assessment, whereby a sequence is expected to close. In such a case, the human–material relations look similar to Phase D. Learners show orientation to each other in an attempt to determine next actions here. The next action may be an ex- tension of the current sequence or the beginning of the next round or some other topical talk. Otherwise, the learners may simply end the pair-work session completely and disengage from interaction. They need to negotiate these options at this sequential position. In this regard, this is a place where the systematicity of activity prompts and the unpredictability of social interaction intersect (cf. Guerrettaz et al., 2021, this issue).

These four phases of participatory configurations summarize—albeit roughly—the recurrent patterns observed in my collection of pair-work cases. In the light of sociomaterialism, these diagrams give a peek into aspects of intra-action present in the apparatus of classroom instruction. The notion of intra-action subsumes the under- standing that what appears to be heterogeneous elements are not separate and discrete but are all entangled and constitute an assemblage (Fen- wick et al., 2011). This means that learners’ actions cannot be understood apart from the ways in which the materials act in pair work. Over- all, we see somewhat limited functions and roles served by the pair-work materials in this con- text. The main role of these prompts is to feed linguistic and sequential cues1 to learners, who then retrieve or read the information in Phase B. In addition, the prompts often lead the learners into utterance-production troubles, which trigger their more interactive engagement. Production troubles are often occasioned in places where in- completeness is marked on the prompt and where learners are oriented to the construction of ab- sent items. Note that the incomplete parts are of- ten tied with the pedagogical targets devised by the teacher or task designer. Such elements may include single lexical items, verb conjugations, and some kind of morphological manipulations, formulaic phrases, or even the entire turn. These pedagogical foci are not only made relevant for this activity per se, but they are also visible in various other places—through the textbook contents and layout; in the organization of the daily lesson plan; on the course schedule handed out to the students; and so forth. For example, the learners are acclimated into the current pedagogical target through a series of lessons leading to the current event. Therefore, pedagogical targets em- bodied in prompts in the form of incompleteness transcend the physical terrain of the materials per se, comprising multitemporal phenomena (i.e., spanning across multiple times and events). It is this multitemporal nature that plays a big part in understanding the intra-action that pair-work prompts are part of. In the next section, I will delve into actual pair-work cases and describe how such complex workings of intra-action are observable in interaction.

TWO LAYERS OF ORIENTATION IN PAIR-WORK INTERACTION

As illustrated in the previous section, the presence of activity prompts changes the ways in which the learners orient to the business of interaction as opposed to when they would interact with- out such materials. The learners’ visible conduct in my database indexes two overlaying orientations to this instructional activity. That is, while there is a clearly individualistic orientation toward the completion of the prescribed sequence con- trolled by the activity prompt, on the one hand, there is also a normative–interactive aspect of this activity, on the other, both of which constitute task-in-process. The former, the pedagogical- activity layer, is concerned with the production of a string of turns prescribed on the activity prompt. In a sense, the pedagogical-activity layer, which is largely concerned with the completion of the prescribed sequence, involves reading and reciting the information written on the prompt, which by itself alludes to the individualistic and private nature of the activity. The focus on the production of semiscripted utterances corresponds to what Seedhouse (2004, 2019) called ‘form- and-accuracy contexts’ in his conceptualization of classroom microcontexts. According to Seed- house, in form-and-accuracy contexts, a focus is placed on “the learners’ production of specific strings of linguistic forms” (2004, p. 144), which do not call for “personal or real-world meanings” (2004, p. 143). Similarly, this layer is also analogous to Walsh’s (2003) ‘materials mode,’ in which the teacher elicits learner responses in relation to the material. While Seedhouse and Walsh were both concerned with teacher-fronted formats of interaction (not pair work), similar characteristics are observed in my pair-work cases.

On the other hand, the other layer, the normative-interaction layer, surfaces if and when- ever some irregularities or uncertainties—such as production trouble, turn-taking, and action formation—arise. The normative-interaction layer points to the interactional procedure found in ordinary conversations. In the current pedagogical context, the normative-interaction layer becomes visible when contingencies of interaction, such as repair and search activities, are occasioned. In this respect, the normative- interaction layer also brings up the relevance of the form-and-accuracy context (Seedhouse, 2004, 2019), where a primary focus is directed at the accurate production of linguistic forms. Learners, nonetheless, occasionally show orientation to something beyond the typical form-and-accuracy context as well (e.g., laughables). In this section, I present particularly remarkable examples in which these layers become visible. These examples involve idiosyncratic interactional procedures—in the sense of deviant cases (Seedhouse, 2019)—which highlight normative orientations shared among participants and reflexively construct the particularity of the current context.

Negotiation of First-Turn Allocation

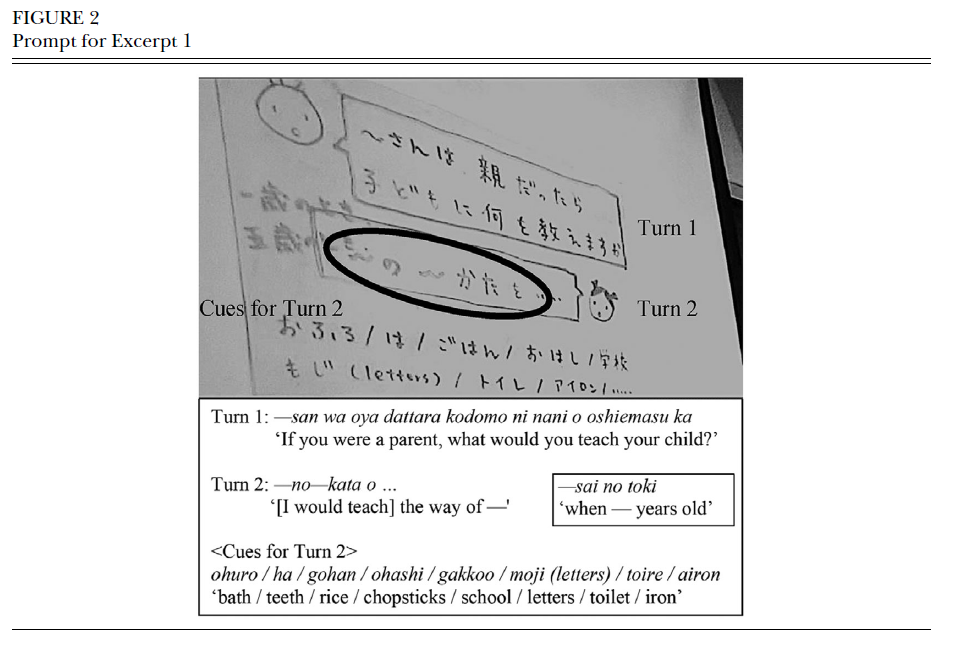

As described earlier, pair-work opening (Phase A) is usually brief yet interactive, where the normative-interaction layer surfaces and becomes visible. However, this is also precisely where learners’ orientation to the two layers of pair work is clearly evident. The following excerpt shows one of the two instances in which learners explicitly negotiate the allocation of the first turn in the opening phase of pair work. In Excerpt 1, the teacher (T) asks a question to the entire class, which prompts two learners (Mark and Luis) to start their pair work.

After the teacher asks the entire class to start working in pairs, at line 6, Mark takes a turn and utters “after you:,” by which he yields the first turn of the prescribed sequence to his partner, Luis. In return, at line 7, Luis starts uttering the first turn. A similar pattern is observed in Excerpt 2: After the teacher gives instruction and prompts the class to work on textbook exercises, at line 6, Henry takes a turn to claim the second turn—the answer turn—which simultaneously assigns the question turn to Brad.

In both cases, a student self-selects to take the turn but explicitly indicates his preference of going after his partner in the prescribed sequence. This seemingly idiosyncratic practice—of taking a turn in order to yield the first turn of the prescribed sequence—shows precisely how these learners are orienting to two separate layers of turn-taking organization generated by the prompt. In a sense, this is a combination of two turn-allocation techniques described by Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson (1974): self-selection by noncurrent speaker and current-speaker- selects-next. At this very first position in a new turn-exchange system (i.e., peer interaction), there is no ‘current’ speaker among the students. Self-selection is the only possible turn-allocation technique to be used in this occasion, and either student can self-select to take the turn.

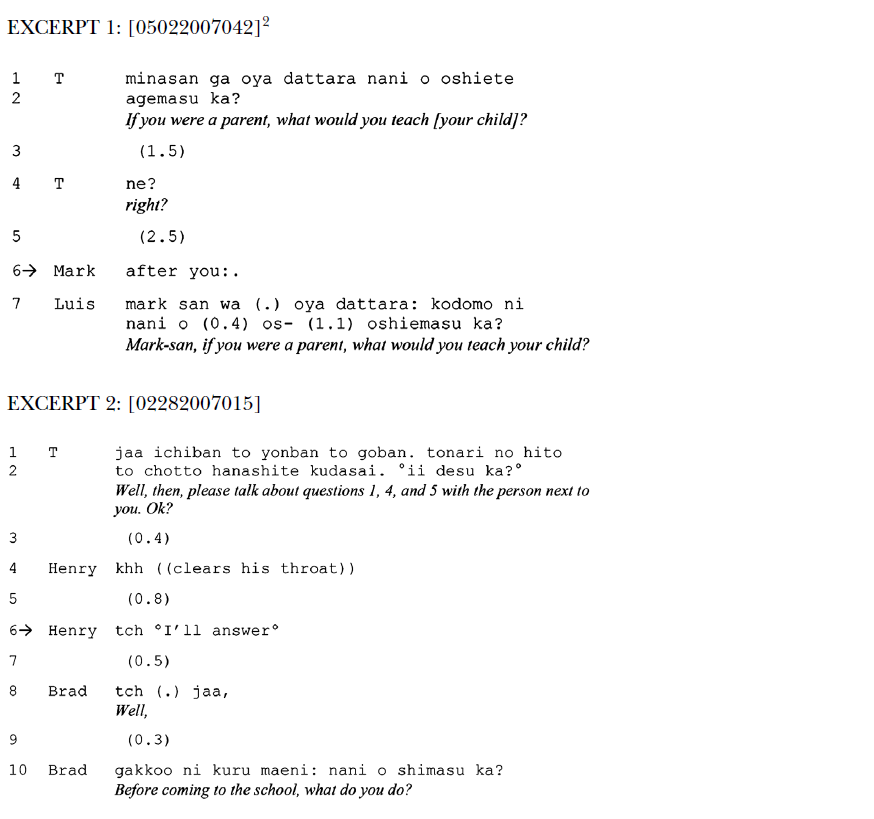

Note that these two cases (Excerpts 1 and 2) are the only instances in which explicit verbal negotiation of turn-taking is observed in my database. In both cases, the self-selected speaker claims to go after his partner. In neither case did the self- selected first speaker ask to go first. This can be accounted for by the fact that the self-selected first speaker always initiates the prescribed sequence by taking the first turn without negotiation, in which case the two layers of turn-taking are apparently converged. While there could be numerous reasons why the learners ask to take the second turn in the prescribed sequence, one likely reason is concerning the design of the prompts used for these activities. In these cases, the second turn involves a fill-in-the-blank element (i.e., an answer turn of the question–answer sequence). As a case in point, Figure 2 presents the prompt used for Excerpt 1.

The layout of this prompt places an emphasis on the incompleteness created in the second turn, where students need to provide answers to the question with the provided linguistic cues. Given that this pair work was assigned after the presentation of the focal grammar point in the second turn (X-no-kata ‘how to do X’), the incompleteness of the prompt coincides with the focus of the lesson. In fact, the focal grammar is also highlighted in red on the original prompt (the corresponding part is circled in Figure 2) whereas other parts of the sequence are in black. Hence, the design features of the prompt, the organization of the day’s lesson plan in which this pair work is situated, the learner’s self-nomination for the second turn, and other elements, are all aligned here pointing to the pedagogical target.

Furthermore, the physical presence of this prompt also allows the learners to see the entirety of the prescribed sequence, including the turn order, turn types, turn length, and even the content of the utterance in each turn. In other words, they can always anticipate various elements of interaction, which are typically variable in ordinary conversations (Sacks et al., 1974). The fixed nature of turns engenders the individualistic orientation of the pedagogical-activity layer. It also increases ‘maneuverability’ within interaction— that is, learners can read the script irrespective of the ongoing talk, which may serve as a resource for the learners to accomplish some activities that would otherwise not be possible. In the next section, I will present cases that illuminate such an aspect of the prompt.

Forward Reading of the Forthcoming Turn

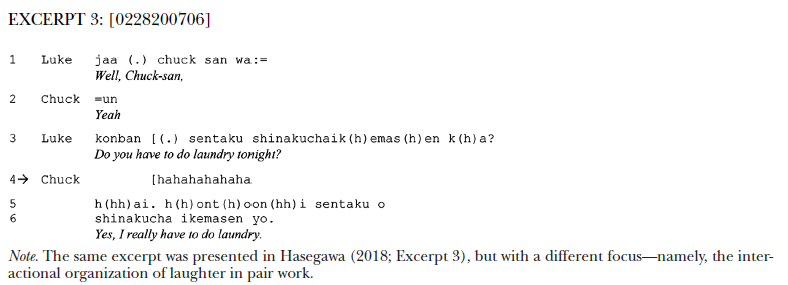

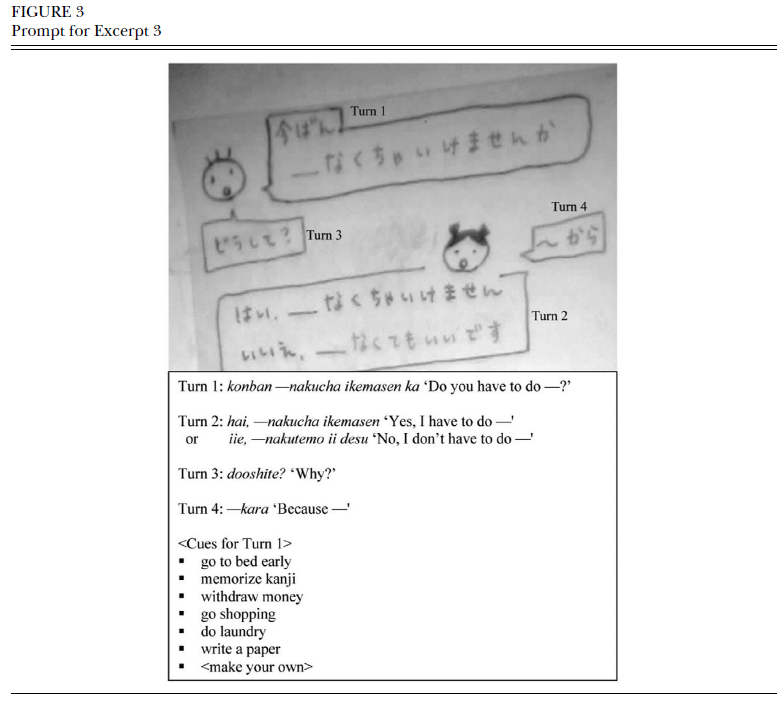

The individualistic orientation of the pedagogical-activity layer is observable especially when the learners are engaged with the exchange of turns that have little incompleteness. Via prompts, not only the speaker but also the recipient can get the same information independently. Excerpt 3 shows an instance where forward reading of the turn content—before it is actually uttered by the speaker—results in an early detection of a laughable item by the recipient of the turn. The prompt used for this pair work is shown in Figure 3.

In line 1, Luke starts his utterance, a large part of which is written on the prompt. In addition to the sentence structure to be used in each turn, the ideas for the question are provided as linguistic cues on the prompt (not included in the screen-shot image). Therefore, the speaker is expected to create a question using those cues along with the sentence structure (such as “go to bed early,” “memorize kanji” ). Excerpt 3 presents the fifth round of this sequence, in which Luke asks Chuck whether he has to do laundry tonight. However, even before Luke gets into the main content of his question (i.e., do laundry), Chuck starts laughing extensively in line 4. Chuck’s laughter is responsive to the content of Luke’s forthcoming utterance. Chuck starts laughing before Luke actually produces it in his turn, and this is made possible because Chuck reads ahead the information on the prompt. Up until this point, the learners are taking turns to proceed through the list of cues shown on the prompt. Therefore, it is clear that they can anticipate what comes up next on the list. Chuck’s gaze directions show this early detection of a laughable on the prompt (see Figures 4–6).

Chuck’s gaze is secured at the prompt be- fore (Figure 4), during (Figures 5, 6), and after his laughter, which indicates that the locus of the laughable can be found somewhere on the prompt. Luke responds to this laughter by reciprocating the same orientation (Figure 6). What is remarkable here is the learners’ simultaneous orientation to the prompt and the co-participant. On the one hand, the learners are reading the prompt independently and privately, displaying little visible attention to each other. This appears to correspond to the individualistic orientation of the pedagogical-activity layer. On the other hand, the exchange of laughter between the learners clearly shows they are indeed attending to each other’s conduct, which brings up the relevance of the normative-interaction layer.

The forward reading of the turn content is enabled by the physical presence of the prompt, but it is also foregrounded by the assumption that Chuck—as the speaker of the second turn—is expected to be filling in the answer slot with his own situational variable. Therefore, his laughter is not only responsive to the content of the prompt but also to his institutional role of an answerer and the imminent need to formulate his response to the question. Meanwhile, Luke is orienting to the completion of his utterance first by not responding to this laughter immediately. He continues his utterance past sentaku shinakucha ‘have to do laundry,’ at which point he produces laughter tokens and reciprocates the laughable orientation.

In short, despite being the recipient of Luke’s question, Chuck retrieves the information before the speaker, who later catches up with the recipient and reciprocates laughter toward the end of his turn. Luke is not necessarily providing information to Chuck because the prompt directly feeds Chuck the information. In this sense, the prompt is transforming the interactional roles of speaker and recipient into something different; both learners are apparently recipients of the in- formation fed by the prompt. Nonetheless, it is also important to note that their responses (e.g., both learners treated the question as laughable) are emergent and interactive in nature. Here, an interesting intersection of the pedagogical-activity layer and the normative-interaction layer—duality of learner orientation—is observable. As I will discuss later, this duality can be seen as what constitutes the simultaneous systematicity and unpredictability of human–material intra-action.

Early Provision of Trouble Solution

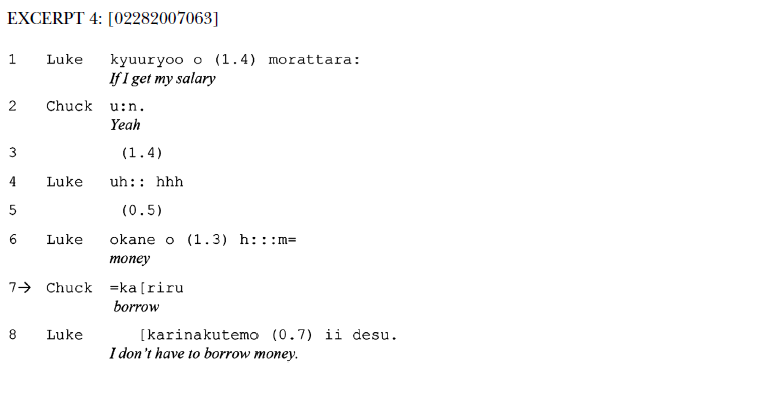

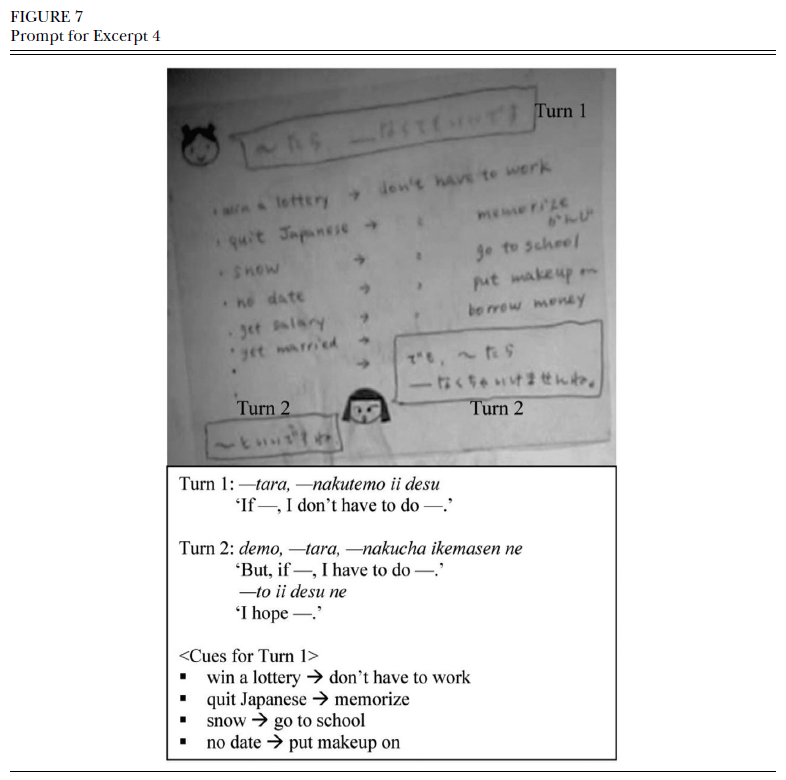

The forward reading of prompts may help detect the ongoing production trouble, which then leads to the early provision of trouble solution. Excerpt 4 presents such an example. Figure 7 shows the prompt used for this pair work.

This is a sentence-making practice. Students are expected to construct the first turn with the focal grammar item, nakutemo ii desu ‘don’t have to.’ Because the cues are provided in English, the learners’ task involves translating them into Japanese. In Excerpt 4, Luke is trying to say, “I don’t have to borrow money if I get my salary.” He indicates a production trouble from the onset, but he manages to proceed with his utterance up to okane o ‘money + direct object particle’ in line 6. However, he pauses there for 1.3 seconds and produces a hesitation marker “h:::m.” This indicates that some kind of search activity is underway. Although Luke is not seeking help from his partner, Chuck produces ka[riru ‘to borrow’ in line 7. This unsolicited assistance may look like a form of anticipatory completion (cf. Lerner, 1991, 1996), which is normally done by way of prosodic, syntactic, and pragmatic projection. Note that this verb is not a new word introduced in the current chapter and, hence, not highlighted as a focus of this activity, either. In fact, the proactive provision of the searched-for item is enabled by the prompt, from which he anticipates the next item that Luke is trying to utter. Interestingly, Chuck produces the verb in the dictionary form rather than using nakutemo ii desu ‘don’t have to’—the target grammar. By providing the verb in the dictionary form, Chuck is preserving Luke’s opportunity to practice the target grammar. In this sense, his assistance, deliberately or accidently, conforms to the pedagogical arrangement of this pair work.

Production troubles trigger the normative-interaction layer to surface as learners collaboratively work at solving them, but the pedagogical- activity layer is also made relevant because the individualistic orientation to the script enabled the proactive provision of the searched-for item. The early detection of production troubles contributes both to the completion of the prescribed sequence (i.e., task) and to the flow of inter- action. In this respect, this case can be seen as congruent working of the two layers. It shows how the two layers may not need to be in competition but can work congruently toward similar goals. Nonetheless, such examples are not common in my database. The pedagogical-activity layer and the normative-interaction layers are usually oriented to different goals, as will be shown next.

Let Trouble Pass (and Return Later)

While the previous examples present the ‘for- ward’ nature of pair-work prompts, learners may also go ‘backward’ in the prescribed sequence, which also points to the intricate intersection of the two layers. As I explained previously, production troubles often trigger the interactive orientation of the normative-interaction layer, but troubles can be manifested when mutual understanding is at stake. In ordinary conversations, nonunderstanding can be displayed through other-initiation of repair (OI). As Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks (1977) discussed, OIs predominantly occur in one sequential position, “the turn just subsequent to the trouble-source turn” (p. 367). In other words, nonunderstanding is indicated by the recipient as early as possible. However, in my database, there were some cases in which a public display of nonunderstanding is delayed past the canonical position (cf. ‘delayed OI’ in Wong, 2000).

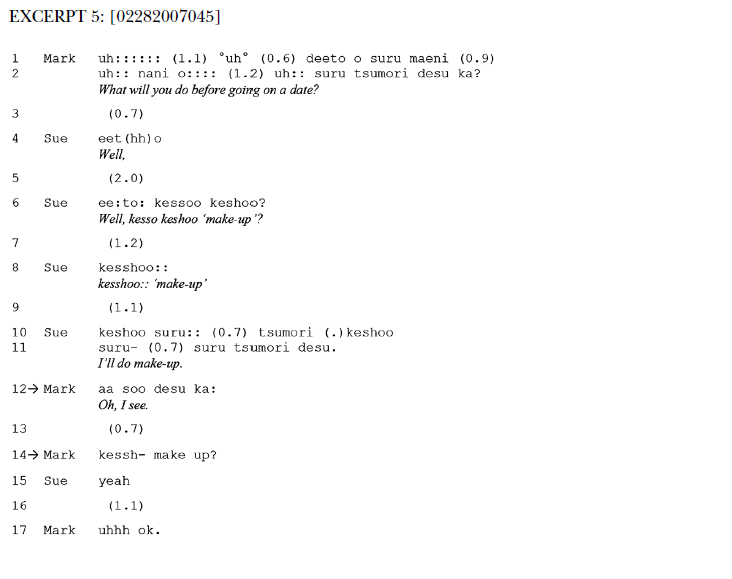

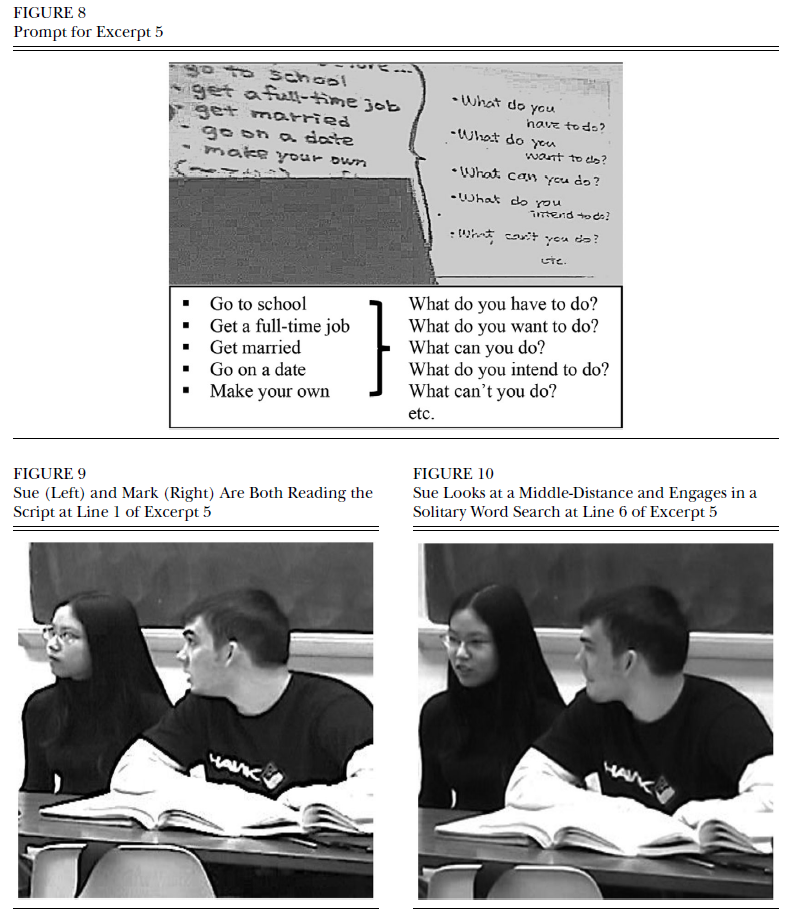

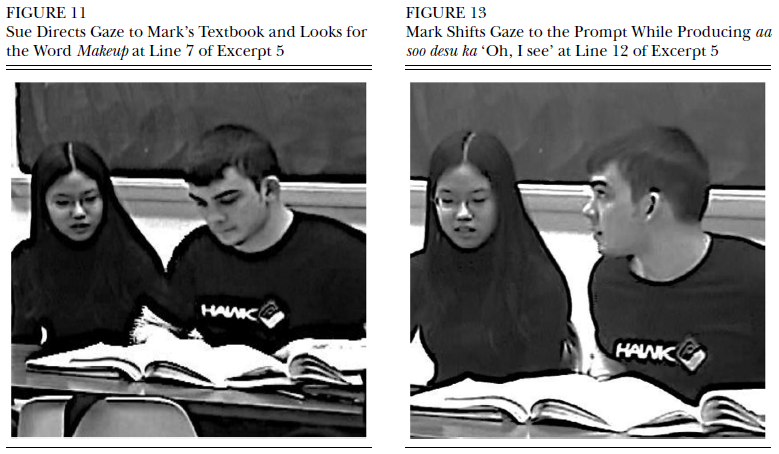

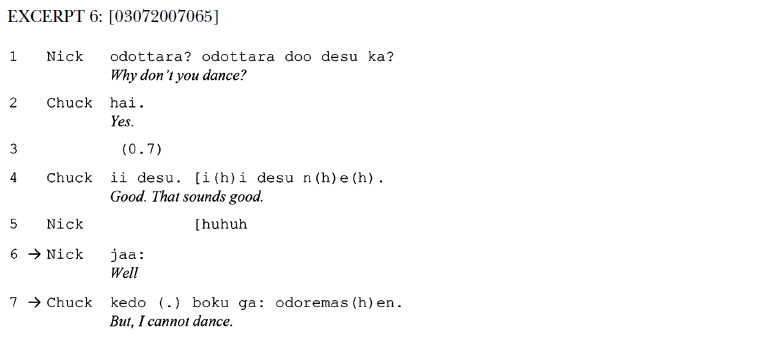

In Excerpt 5, Mark and Sue are working on a question–answer sequence prescribed in the activity prompt (Figure 8). In this pair work, the students are expected to ask questions using the grammar construction of maeni ‘before’ or tekara ‘after,’ along with the linguistic cues provided in English. For example, a question like What do you want to do before you get married? can be created by combining before, get married, and what do you want to do? In line 1, Mark asks a question, deeto o suru maeni nani o suru tsumori desu ka? ‘what do you plan to do before you go on a date?’ In her answer, Sue shows a production trouble with the word keshoo ‘makeup.’ The trouble is indicated through multiple occurrences of self-repair, try-marking (i.e., rising intonation), as well as gaze shifts (see Figures 9–12).

As soon as Sue starts her utterance, she shifts her gaze to a middle-distance (Figure 10), which indicates a solitary word search in progress (e.g., Goodwin, 1987). Sue try-marks her utterance with a rising intonation, keshoo? in line 6, which does not get any response from Mark. Sue then shifts her gaze toward the textbook located in front of Mark, from which she reads out the word kesshoo (Figure 11). Judging from the way she obtains the word, it is apparent that the vocabulary page of the textbook is open (cf. Mori & Hasegawa, 2009). In lines 10–11, Sue completes her utterance and directs her gaze toward the prompt (Figure 12). Up until this moment, Mark’s nonunderstanding of the word keshoo has not been displayed, but this is precisely the moment where an OI is normally occasioned if understanding is at stake. Instead of initiating a repair, Mark utters an acknowledgment token, aa soo desu ka: ‘oh, I see,’ while looking at the front screen (Figure 13). However, Mark then initiates an OI in line 14, which is seemingly displaced from its canonical position.

Several important observations can be made for this excerpt. First, Mark’s acknowledgment token is not written on the prompt. Rather, it was included as part of the sequence when the activity prompt was presented by the teacher and prac- ticed by the whole class right before this pair-work session. Interestingly, Mark shifts his gaze to the prompt when producing this acknowledgment token, displaying his orientation to the prescribed sequence (Figure 13). This indicates that the control of the prompt actually goes beyond its current physical presence to encompass its us- age from the preceding events, including the prepair-work teacher-fronted interaction where the prompt was first introduced and practiced with the whole class. As such, the materials use is better conceptualized as spanning over multiple events and times (i.e., multitemporality), rather than being captured at a single point in time.

Second, Mark’s OI is delayed past the canonical placement due to the provision of this acknowledgment token. Wong (2000) argued that nonnative speakers occasionally delay their OIs due to the lateness of analysis or “not-yet-mature understanding” (p. 261). However, by the time Mark produced an acknowledgment token in line 12, keshoo had already been brought into light as a trouble-indicative item through Sue’s engage- ment in a solitary word search. As Goodwin (1987) noted, a “speaker’s display of uncertainty draws the material so marked into heightened promi- nence” (p. 116), which would not be made so otherwise. As such, Wong’s observation does not seem to apply to the current case. To be more precise, rather than the lateness of analysis, it is the insertion of the acknowledgment token—clearly oriented to by Mark as part of the prescribed sequence—that delayed the OI.

It is interesting to note that Mark let the trouble pass first and returned to the trouble after closing the sequence. Here, we see two competing orientations—toward the completion of the sequence (pedagogical-activity layer) and the solution of nonunderstanding (normative-interaction layer). The incongruent working of the two layers is evident here, which points to different kinds of intersubjectivity made relevant in this context. Intersubjectivity presupposes the reciprocity of perspectives between participants as fundamental in dealing with the indexicality of social activities (cf. Zaner, 1961). On the one hand, resolving nonunderstanding and achieving understanding in social interaction is aimed at the defense of fundamental intersubjectivity (e.g., Schegloff, 1992). On the other hand, an impetus for the completion of the prescribed sequence (i.e., the acknowledgment token in line 12) while violating the normal procedural orientation to the remedy of nonunderstanding (i.e., delayed OI in line 14) also reflects the learners’ shared understanding of this particular context. That is, they understand the primary goal of this pair work to be the completion of the assigned script rather than engaging in a naturalistic conversation. As such, the primacy of task completion (i.e., prescribed sequence) is seemingly sanctioned and mutually oriented to by the learners. Divergent orientations such as those seen here appear to surface most vividly when the pedagogical control embedded in the materials ceases toward the end of the prescribed sequence, which will be examined next.

Negotiation of Next Possible Actions

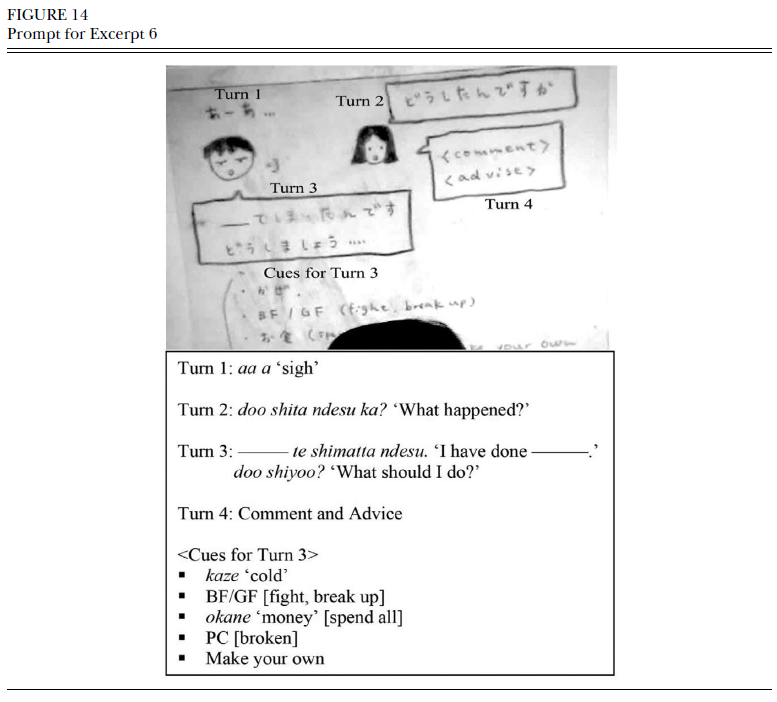

When prescribed sequences come to an end or a closure-relevant position (Phase D), learners have multiple options with regard to next possible actions. This multiplicity makes this position a frequent place where divergent orientations to the two layers may be observed. The next example shows such an instance (Excerpt 6). The prompt presents four turns (Figure 14). The focal segment shows the final turn of the prescribed sequence. Prior to this segment, Chuck has said gaaruhurendo to kenka shite wakarete shimatta ndesu ‘I had a fight with my girlfriend and broke up with her’ for the third turn slot.

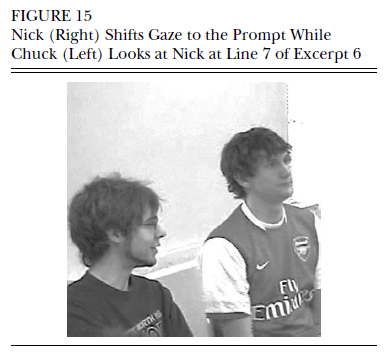

In line 1, Nick provides his advice to Chuck, which Nick receives with hai ‘yes.’ By this receipt token, the sequence is apparently complete, but after a 0.7-second silence, Chuck adds an assessment, ii desu ne ‘that sounds good,’ in line 4. Note this additional utterance is produced in a nonserious manner with laugh particles inserted (i.e., denoted with “(h)”). This orientation is shared by Nick, who also produces laughter in line 5. At this moment, several possibilities open up as a relevant next action. One possibility is to continue the shared laughter sequence by extending the laughter or renewing a laughable (e.g., Glenn, 2003). Another possibility is to continue this conversation but without laughter (i.e., topical talk). Moreover, the learners may move on to the next round of the scripted sequence or end this session completely. As shown in lines 6 and 7, Nick and Chuck are showing divergent orientations. Nick apparently tries starting another round of the scripted sequence, which is demonstrated by his gaze shift to the prompt (Figure 15), along with jaa: ‘well.’ Chuck, however, looks at his partner and continues with the shared laughter sequence by renewing a laughable in line 7.

Their divergent orientations are occasioned at the sequential boundary created by the prompt. Nick orients to the completion of the task while Chuck engages in unscripted spontaneous talk. It appears that both the pedagogical-activity layer and the normative-interaction layer are made relevant—although incongruently by the two learners—at this sequential position. It should also be noted that their competing orientations are demonstrated sequentially rather than con- currently. Nick first shows his orientation to resume the sequence, and Chuck recognizes this as he sees Nick’s gaze direction (Figure 15). Nonetheless, he still adds his laughable utterance to override Nick’s upcoming action. In examining similar cases, Hasegawa (2018) previously dis- cussed how laughter could trigger and promote a spontaneous exchange of utterances in a successive way. Chuck’s orientation to the extension of the shared laughter is similarly evident in this case.

DISCUSSION

With the sample cases of pair work, I have demonstrated how two overlaying orientations are displayed as learners engaged with prescribed sequences specified on pair-work prompts. I used the concept of layers to analyze the intricacy and the subtlety involved in the use of learning materials, as well as the conflicting capabilities of the materials. In a sociomaterialist sense, the examination of these layers helps us better understand the “dynamism [of. . .] sociomaterial intra-actions” emerging in this context (Guerrettaz et al., 2021, p. 8). The pedagogical-activity layer largely points to the systematicity while the normative-interaction layer is occasioned with the unpredictability of interaction. As such, the two layers allow us to examine the simultaneous systematicity and unpredictability of materials use.

On the one hand, the pedagogical-activity layer calls for the individualistic procedure of completing the prescribed sequence, which clearly deviates from the normative interactional procedure found in ordinary conversations. The materials (i.e., prompts) used for pair work in my database largely serve as an information feeder to the learners. In this sense, these prompts may be seen as the extended presence of the teacher, who is remotely intervening as the third participant of pair work. In other words, the power and agency of teacher or task designer are displaced and distributed through the physical prompt presented to the learners (McGregor, 2014). Importantly, moreover, how a prompt is used appears to be linked not only with its current physical presence but also with its past usages. Mark’s treatment of an acknowledgment token as part of the prescribed sequence, for example, is apparently derived from the pre-pair-work instruction and practice with the whole class. Hence, it is not sufficient to focus merely on the design features of materials, but the multitemporality of materials use (i.e., how materials are used across times and events) should also be considered. In fact, the multitemporality allows ‘patterns’ in materials use to emerge.

On the other hand, the normative-interaction layer surfaces when learners are working through some kind of contingency, as often found in the defense of intersubjectivity and the remedial or corrective actions undertaken, such as repair and search activities. Such contingencies may include production trouble, nonunderstanding, and negotiation of next actions in a closure-relevant position. From a pedagogical viewpoint, these contingencies appear to be full of learning opportunities because learners may engage in various interactional practices. Especially if learning is conceptualized as increasingly diversified repertoires of interactional procedures (e.g., Hall, 2018; Pekarek Doehler, 2019), contingencies that arise while grappling with the semiscripted sequence may contribute to development in this regard. It is important to note that although these contingencies may appear random and disorderly, the troubles and the resulting remedial actions identified in this article are largely responsive to the incompleteness designed by the teacher or task designer (cf. Hazel & Mortensen, 2019). Particular design features—placement, size, and type of incompleteness embedded in the prescribed sequence—have much to do with the ways in which these layers emerge in interaction.

Furthermore, while the pedagogical-activity layer and the normative-interaction layer may work toward similar goals (e.g., Excerpt 4), they may compete against each other for different goals (e.g., Excerpts 5 and 6). The incongruent working of two layers may be observed sequentially within individuals (Excerpt 5) or across different learners (Excerpt 6). As for the former, for example, we have seen Mark’s conflicting orientations to the completion of the prescribed sequence, on the one hand, and the solution of nonunderstanding, on the other, as examined in Excerpt 5. As for the latter, the sequential ambiguity generated toward the end of the prescribed sequence appears to be accountable for leading Chuck and Nick into negotiating options for the next possible actions, as seen in Excerpt 6.

To summarize various functions served by the pair-work prompts examined in this study, the following three are evident: (a) information feeder, (b) linguistic-features elicitor, and (c) spontaneous-talk instigator. The role of prompts as an information feeder encourages learners to read and recite the content of the material individually, which may not necessitate the normal interactional procedure, such as turn taking and turn projection. The prompts also work to elicit specific linguistic features that are pedagogically intended and embodied as incomplete elements. This function often leads learners into production troubles or other contingencies that require corrections or remedial actions, such as repair and word search. Sequential ambiguity created at the end of the scripted sequences generates opportunities for learners to negotiate possible next actions, which enables them to engage in talk beyond what is controlled by the teacher or task designer. This last function relies on learners’ varying understandings of the ongoing context. Some students try to stick with the prescribed sequence while others may try to extend the conversation further. It is especially interesting to see how the learners may construct talk beyond what is prescribed in the prompt at this sequential position because it allows for various forms of participation (van Lier, 1996; Waring, 2016). Bannink (2002) reported on a case of spontaneous talk initiated after the official task ended. Similarly, I found re- current occurrences of additional talk starting after prescribed sequences were completed. Again, these examples are indicative of the paradoxical coexistence of unpredictability and systematicity in teaching and learning (Fenwick et al., 2011). If our goal is to maintain a fine balance between creating planned and controlled pedagogical foci and simultaneously encouraging spontaneous ex- changes of turns between learners, we certainly need a fuller understanding of various facets of pair work.

In closing, I would like to return to the conflicting notions of task-as-workplan and task- in-process introduced in the beginning of this article. As I explained in the beginning, this study set out to closely examine task-in-process by focusing on the actual learner interactions during pair work. My analysis has shown some idiosyncratic (deviant) cases whereby the underlying normative orientations as well as context-specific orientations to the ongoing event became visible. By making use of the sociomaterial concepts, intra-action in particular, my interpretive scope has broadened to encompass how human and nonhuman relations are intricately configured. While ‘inter-action’ places a conceptual emphasis on human–human (agency–agency) relations and exchanges, ‘intra-action’ evokes more explicit attention to nonhuman elements (e.g., materials). This added emphasis on nonhuman elements that constitute a part of the complex whole may dissolute the epistemological divide between task-as-workplan and task-in-process discussed in the past SLA research. That is to say, the investigation of pair work may most benefit by involving the close analysis of task-in-process—in which not only learner–learner interaction is the focus but also intra-actions of various aspects surrounding materials are examined. More future research on classroom materials use from this viewpoint are earnestly expected.

注:本文选自The Modern Language Journal 105(2021)65-85。由于篇幅所限,注释和参考文献已省略。