Abstract

In light of the growing agreement on the critical impact that materials can have on teaching and learning, classroom-based research on materials use in natural educational contexts has become increasingly urgent. This study aims to explore language teachers’ use of instructional materials in classroom settings. Drawing on the analysis of materials, interviews, and lesson observations from cases of three Chinese English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers and their six students, this study identified six interactive processes of materials use, based on which teachers’ pedagogical reasoning that enabled each process of materials use was unpacked. Through the theoretical lens of Keller and Keller’s anthropology of knowledge and Wartofsky’s categorization of artifacts, this article unraveled the relationship between teacher knowledge and practice in materials use and disentangled the multilayered roles of curriculum materials. The findings not only contribute to the conceptualization of materials use in language education but also suggest effective ways of enhancing the inservice professional development through materials use and development in natural educational contexts.

Keywords

language teachers, materials use, pedagogical reasoning, teacher knowledge

Introduction

In language education, the pivotal role of materials, (i.e., all the resources that are developed and used for teaching and learning either by organizations or individuals) in terms of defining the content of teaching has been well documented (Littlejohn, 2011; Tarone, 2014). Prior studies have provided convincing evidence that textbooks alone represent the written curriculum in language classrooms across the world (Guerrettaz & Johnston, 2013; Karvonen et al., 2018; Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2018). What we teach matters to how we teach and thereby how students learn (Steiner, 2018). Thus, exploring how and why teachers used the materials at classroom settings has become increasingly urgent in mainstream education in general (Remillard, 2018) and language education in particular (Jakonen, 2015). This study examines language teachers’ enactment of instruction through the use of materials. It particularly focuses on university EFL teachers’ use of a prescribed textbook to enact instruction in higher education in China, a nationalized curriculum context with the largest population of foreign language learners in the world. It is of relevance to other educational contexts in the world due to the expanding number of Chinese students who pursue further study globally.

How they were taught, and particularly, in different ways of curriculum enactment in China, would be valuable information to university instructors and researchers of higher education across contexts. Furthermore, a more nuanced picture of class- room-based curriculum enactment could advance our concep- tual understanding of material use, an ostensibly straightforward yet multifaceted teaching practice.

With the above aims in mind, we conducted a qualitative case study, involving three Chinese EFL teachers and six students at one university in China, to address the following three research questions:

Research Question 1 (RQ1): How did Chinese EFL teachers use mandatory textbooks to enact instruction in classroom settings?

Research Question 2 (RQ2): What is the relation between teacher knowledge and materials use?

Research Question 3 (RQ3): What are the roles of text- books in materials use?

Literature Review

Materials use refers to “the ways that participants in language learning environments actually employ and interact with materials” (Guerrettaz et al., 2018, p. 38). Despite the constant endeavor to the development and evaluation of language materials at the level of the page (Harwood, 2017), classroom-based research focusing on materials use has been scarce (Matsumoto, 2019). In the past few years, more and more linguistic scholars have noticed the importance of shifting the research focus of materials development from merely on analyzing materials to exploring the actual usage of these materials in natural educational environments (see, for example, Harwood, 2017; Tomlinson, 2012). Furthermore, these turned materials use into a burgeoning research area in language education, particularly in applied linguistics (Jakonen, 2015). Responding to Harwood’s (2017) recent call to learn from materials research in mainstream education both methodologically and theoretically, we systematically reviewed the research foci and theoretical underpinnings of main- stream educational studies concerning materials use to shed light on the current study.

In comparison to such paucity of research of materials use in applied linguistics, some notable studies have been under- taken in mathematics, science, and history at primary and secondary schools in the United States and Europe (Brown, 2009; Choppin, 2011; Gueudet & Trouche, 2012; Pepin et al., 2013; Reisman & Fogo, 2016; Remillard, 2005, 2009; Sherin & Drake, 2009). Studies in mainstream education sought to understand how and why teachers adapted materials by mainly drawing on lesson observations and the solicitation of teachers’ perceptions. They focused on teachers’ divergent ways of attending to curriculum materials (Brown, 2009; Sherin & Drake, 2009), influencing factors (Remillard, 2005), and the educative function of curriculum materials on the part of teachers (Choppin, 2011; Davis & Krajcik, 2005; Reisman & Fogo, 2016).

Among them, two seminal works are relevant to the current study. In his qualitative study on three secondary science teachers’ use of an inquiry-based textbook in the United States, Brown (2009) regarded curriculum materials as artifacts and defined teachers’ pedagogical design capacity in using curriculum materials, that is, a competence that enables teachers to leverage all resources to craft classroom instruction. Rooted in the same sociocultural theory on the tool- mediated human activity (e.g., Cole & Engeström, 1997; Vygotsky, 1978), Remillard’s (2005) participatory perspective regarded the relationship between teachers an curriculum as interactive along with a range of influencing factors including teachers’ resources and features of curriculum materials which will jointly affect the outcome of classroom instruction.

Scholars in language education have long recognized teachers’ expertise in using materials (e.g., Grossman, 1990; Richards, 2010; Tomlinson, 2012). However, the “funds of knowledge” (Seargeant & Erling, 2011) that teachers deployed to enact curriculum is recently identified in four domains, namely, the curriculum materials (Remillard & Kim, 2017), disciplines (Brown, 2009; Remillard, 2018), students (Gueudet & Trouche, 2012), and contexts (Choppin, 2009). Based on Shulman’s (1986) categorization of teacher knowledge, Remillard and Kim (2017) termed knowledge of curriculum embedded mathematics to define what mathematics teachers need to activate to design instruction through the use of curriculum materials. This knowledge was at both content and pedagogic levels. Similarly, Choppin (2009) proposed curriculum-context knowledge, a subdomain of teachers’ curricular knowledge, that appeared in mathematics teachers’ enactment of curriculum materials to engage students in a certain context. He noticed the growth of teachers’ curriculum-context knowledge through the repetitive usage of the same materials. Gueudet and Trouche (2012) incorporated students’ responses into teachers’ professional growth system owing to teachers’ refinement of instruction based on their reflections on students’ responses. More recently, Remillard (2018) unraveled the nature of mathe- matics teachers’ pedagogical design capacity, that is, a capacity to mobilize personal and curricular resources to construct instructional episodes (Brown, 2009), and high- lighted the importance of both teachers’ interpretive capaci- ties and the comprehensibility of teachers’ guides in the whole process of transforming curricular tools into instruments (Gueudet & Trouche, 2012). All these studies unveiled the possible knowledge landscapes that teachers might traverse to enact curriculum materials in mainstream education.

Influenced by these seminal works, researchers started to discern materials use in the lens of sociocultural theories (e.g., Li & Harfitt, 2017, 2018; Mesa & Griffiths, 2012). As distinct from a static view of materials development research in language education, sociocultural theories highlighted the dynamic nature of materials use by focusing on two forms of agency. One is exercised by teachers when drawing on curriculum materials to enact instruction. The other originates from the curriculum materials, which provided both affordances and constraints to teachers’ enactment of curriculum. In other words, curriculum materials are shaped by and have the potential to influence classroom teaching (Wartofsky, 1979; Wertsch, 1998).The theoretical lens here advanced our knowledge on materials use in terms of portraying a fuller picture of this ubiquitous yet under-specified area of teach- ing (Remillard, 2018).

Theoretical Perspectives

This study employs the anthropology of knowledge by Keller and Keller (1996) to unpack teachers’ pedagogical reasoning behind their use of materials and builds on Wartofsky’s (1979) categorization of artifacts to unravel the multilayered meanings of curriculum materials. Using materials for teaching is analogous to human’s use of tools for creative production (Brown, 2009). According to Keller and Keller (1996), producing a creative product entails three cognitive processes, that is, drawing on a stock of knowledge, following an umbrella plan composed of a series of designs, and formulating a constellation that enables the accomplishment of each step of the plan. These processes evolve until the anticipated goal is reached. The constructs of the stock of knowledge, umbrella plans, and constellations that are proposed to conceptualize the human cognition situated in tool use (Keller & Keller, 1996) are appropriate to capture teachers’ cognitive processes of materials use, and thus used as the theoretical framework for the present study (cf. Li, 2020).

Curriculum materials are regarded as artifacts with both materials characteristics and cultural meaning (Edward, 2014; Wertsch, 1998). Miettenen (2001) pinpointed that “artefacts carry intentions and norms of cognition and form part of the agency of the activity” (p. 301). In other words, artifacts are the bearers of the designers’ intentions, which will function through affordances and constraints (Norman, 2013). Van Lier (2004) emphasized the interpretive relation- ship between humans and artifacts. Humans perceive the affordances of artifacts to capture the possible meaning and action deposited in the artifacts. Wartofsky (1979) classified artifacts based on the modes of representation at three levels, namely, primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. These three levels are not discrete or hierarchical. Any activity could entail all three modes of representations (Habib & Wittek, 2007). The primary artifact refers to its material dimension, which constitutes the physical, visual, and substantive forms of the artifacts. The secondary artifact consists of the representation of the primary artifacts, such as the design intentions, the potential meanings and actions (Van Lier, 2004), which give hints to human beings to interpret. The tertiary artifact is imaginative, which stands for the imagined or possible worlds that may exist in the artifacts. Through this theoretical lens, multilayered interactions between actors and artifacts will be analyzed.

Method

Background of the Study

This classroom-based study examining EFL teachers’ use of mandatory textbooks was positioned in College English courses of English language education in China. Currently, more than 27 million students are enrolling in higher education in China (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2018).

College English course is the compulsory course for all majors other than English for at least one academic year (Wang, 2007). New College English textbooks are compiled by a government-appointed panel of experts and are disseminated to all universities and colleges to support newly implemented national curriculum reform (Wang, 2007). The target textbook series (New Standard College English Series) is adopted by more than 200 universities, meaning nearly 2 million students are using the same textbooks in China (Huang, 2011). Since 2011, the target university has prescribed the textbook series. It was chosen as the research base due to its social status and ranking in higher education as enlisted as part of the “Double First-Class” project (i.e., the Chinese government’s initiative with funding support on selected research fields of studies on a 5-year cycle to expand the number of highly ranked universities by 2050) in China.

Participants

There were three female teacher participants (Alice, Betty, and Cathy, all pseudonyms). They ranged in teaching experiences from 2 to 23 years and were of three nonnative English speakers with master’s degrees in the areas of applied linguistics, Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL), and English literature. All of them had 1 to 2 years of overseas experience (e.g., Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom) with one holding a master’s degree in the United Kingdom (Alice). Following the intensity sampling principle (Patton, 2005), the teacher participants were chosen due to the teachers’ willingness and interest to elaborate on their use of materials. All of the teachers were using the same materials and teaching students at the intermediate language proficiency level at the same university. Six students with two from each teacher’s class volunteered to participate in this study. All of them are majoring in non-English subjects.

Data Collection

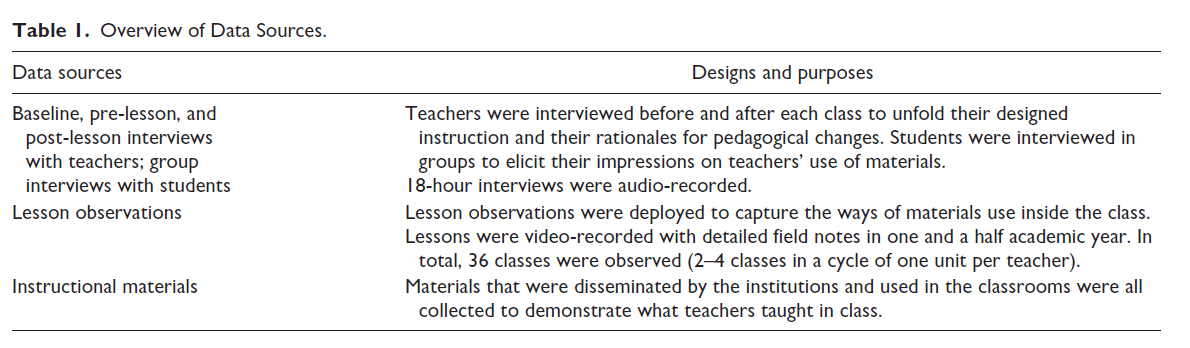

The data sources for this study include semi-structured interviews, classroom observations, and documents. The baseline, pre-lesson, and post-lesson interviews were designed to elicit teachers’ perceptions on the curriculum materials, their use of materials before and during the lessons, and their rationales. Lesson observations were video- recorded by the first author. The documents consist of all the teaching materials that were used by the teachers, including the target textbook series (i.e., Student’s Book, Teacher’s Guide, and auxiliary PowerPoint slides) and teacher-prepared materials in all sorts of modalities. Students were interviewed collectively to elicit their impression on teachers’ use of materials, which were used to triangulate the data from teachers. Table 1 shows the design and purposes of each research instrument.

Data Analysis

We transcribed all the interviews verbatim and coded them by following Corbin and Strauss’ (2015) scheme of open, axial, and selective coding. Through recursive discussions, we looked for commonalities and differences in teachers’ use of materials before and during the class. We resolved the discrepancies in our initial coding through rounds of negotiation, and we finally agreed on the coding falling into five general categories: identifying, assessing, adapting, improvising, and reconceiving. The lesson observations in the form of classroom discourse were also transcribed verbatim to capture teachers’ enacted instruction in class. The analysis of documents involved detailed descriptions of the pedagogical objectives, and how and what these materials communicated with teachers and students. The purposes of presenting and analyzing these documents are twofold: (a) to provide readers with the background of what teachers and students are working with and (2) to provide a sound basis for com- paring and contrasting with enacted instruction and the intended one. All transcriptions were given to participants for member checking.

Findings

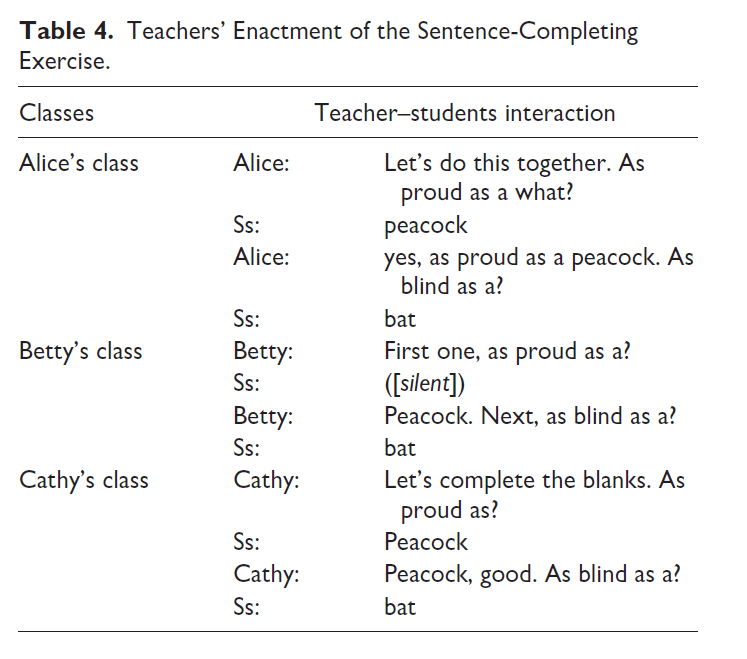

Teachers’ use of materials mainly demonstrated in six inter-active processes, namely identifying, evaluating, adapting, improvising, reflecting, and reconceiving. Each process will be presented with supporting evidence to unveil the rationales for teachers’ decision-making as follows.

Identifying

The most prominent process of materials use was to turn the text into the lived instruction. Before enacting each unit, all teacher participants acknowledged that they would identify essential knowledge and skills from the texts, as the excerpts show:

Make sure what background information needs to be supplemented; which key phrases and words students need to master; get a general sense of the structure of the passage. (Betty’s pre-lesson interview)

I’ll think about what the salient points are and what can be extracted from the unit in the process of reading the passages and doing the exercises. (Alice’s pre-lesson interview)

I’ll try to understand the topic and just think about some related activities or exercises to introduce this topic to the students. (Cathy’s pre-lesson interview)

The identification of salient knowledge and skills was influ- enced by teachers’ perceptions of the pedagogical focuses. For instance, when doing an activity of chronological order- ing events in the passage, Alice emphasized the usage of tense and was aware that there is pedagogical knowledge deposited in the materials, as the excerpt illustrates:

For example, the usage of tense in unit 7 . . . The knowledge like this, if teachers could extract it from the passage, explain it to students, and apply this into other similar scenarios, for instance, let them read a passage with similar language features, then the teaching must be more productive. (Alice’s post-lesson interview)

By contrast, while carrying out the same activity, Cathy talked about a totally different teaching point, as her lesson observation shows:

If you think you still have trouble understanding the time sequence in the passage, you’d better spend more time reading the passage. It is not difficult to comprehend the passage, but the time sequence of it, particularly the use of flashback. Flashback is embedded with a flashback. So it is very difficult to sort out the exact time sequence. You’d better spend more time on the time sequence of the passage after class. (Cathy’s lesson observation)

After analyzing the given instruction of the task (i.e., number the events in the order in which they happen), we found that the linguistic, grammatical, and pedagogical knowledge required for carrying out this task was completely absent in the Student’s Book and Teacher’s Guide. To actualize this given instruction with no explicit pedagogical knowledge into an activity, teachers’ knowledge of teaching strategies, learning strategies, and the awareness of students’ under- standing were all prerequisite.

Teachers’ perception of the potential pedagogical knowledge represented in the materials might not be in line with the original intention of the designer. For instance, Betty asked her students to refer vocabulary book while doing a vocabulary exercise which was particularly designed to train students to guess the meaning from the context. The process of identifying indicates that the relationship between teachers and textbooks is interpretive and dynamic.

Evaluating the Appropriacy of the Materials

Teachers also need to evaluate the appropriacy of teaching materials through assessing students’ performances, responses, and reactions. Students’ unsatisfactory performances could trigger teachers to adapt the original instruction or improvise a new one. For instance, upon seeing that her students failed to complete a reading comprehension exercise—that is, the chronological ordering of events in the passage—Alice instructed on the usage of tense in the pas- sage, as this excerpt demonstrates:

Pay attention to the tense. “Had done” is indicating things happened in the past of the past. (Alice’s lesson observation)

She further explained that highlighting this instruction was due to her evaluation of the content of materials and students’ performances, as this excerpt shows:

At first, I didn’t expect my students to meet such great trouble in reordering the happenings. I didn’t expect the exercise was that difficult for them. I then attributed it to the cause of tense. They didn’t catch the tense, so they ordered in a mess. They believed they should order the events according to the original passage. (Alice’s post-lesson interview)

Although students’ responses played a determining role in teachers’ adaptation of their planned instruction, the embedded pedagogical knowledge also had a say in the effectiveness of enacting the materials. As mentioned earlier, teachers need to identify the pedagogical focuses of the text before transforming them into real teaching practice. The explicitness of the editor’s pedagogical intention deposited in each text became crucial in determining how the teachers would fully discern these materials:

I think the editor must have chosen the texts for some reasons based on thorough thinking, which must be scientific and systematic. Then I hope to find out what he wants to say (the editor’s intention). But I didn’t find it out in the Teachers’ Book. It didn’t tell you, or sometimes it told you something that you didn’t think was particularly important. So this is very demanding for teachers. (Alice’s pre-lesson interview)

Due to the opacity of the editor’s intentions, teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge was badly required. In this case, Alice’s knowledge of how the passage was structured (i.e., knowledge about the text), knowledge about the English language, and evaluative knowledge of students’ mistakes facilitated her improvisation of the more appropriate instruction to reach her pedagogical goals.

Adapting

Teachers’ adaptation manifested itself in supplementing extra materials, modifying instructions, or changing the intended pedagogical goals of the original materials.

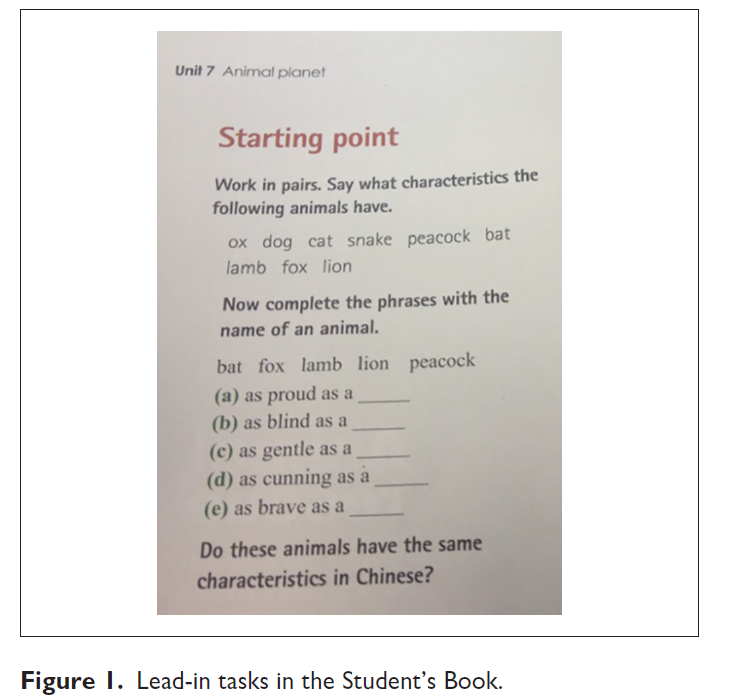

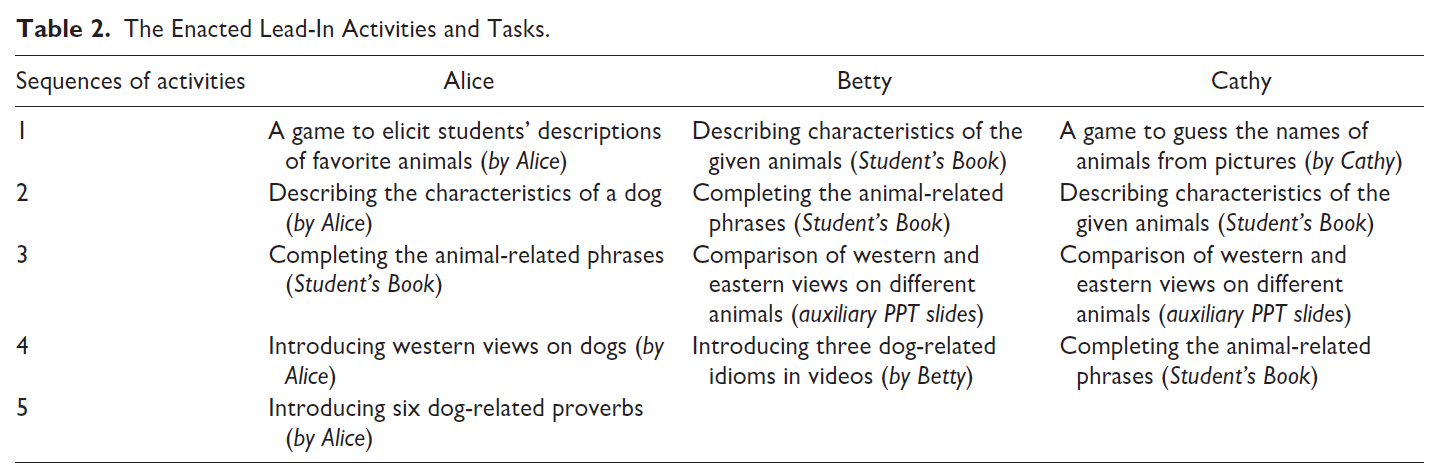

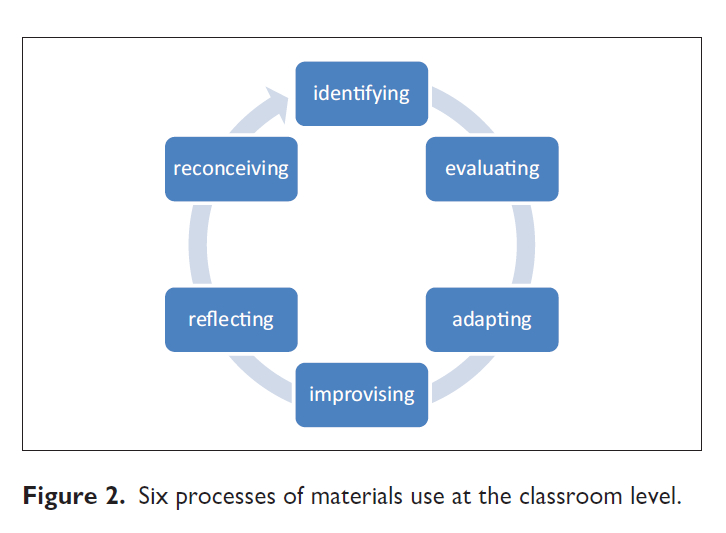

Supplementing materials. Figure 1 is the starting point tasks in the Student’s Book. Table 2 outlines a comparison of teachers’ enacted warm-up activities with the origins of the teaching materials in the corresponding brackets.

The selection of extra activities was affected by teachers’ teaching style, personal preferences, and access to resources. For instance, the enacted lead-in activities were mostly inspired by the textbook in terms of content (e.g., Alice’s Activity 3, Betty’s Activity 2 and Cathy’s Activity 4, Betty’s Activity 1 and Cathy’s Activity 2 were identical and all from the Student’s Book). Their preferences of content and broad access to resources also had a say in the design of the activities. For example, Alice’s Activities 2 and 4 were related to her fondness of dogs, and Alice’s Activities 4 and 5 were from online resources. In her post-lesson interview, she pro- fessed the essence of her teaching style and her agency in adapting the materials, as the extracts show:

In order not to bore my students, I would arouse their interest amid my teaching. Thus, I need to incorporate more interesting materials to stimulate them. When preparing for a lesson, I will switch my identity as my students to see whether the designed activities could arouse their interest or not. (Alice’s post-lesson interview)

Teachers’ adaptation was also influenced by students’ appeals, needs, and language proficiency. For instance, com- pared with merely describing the characteristics of given ani- mals, Alice’s design of letting students describe their favorite animals was more associated with students’ lives, which was more engaging. Students’ positive comments on Alice’s lead- in activities confirmed the appeal and success of her adaptation, as the extract shows:

Our teacher will first introduce the topic by playing games with us. This is more interesting. The textbook became an auxiliary material. (Alice’s female student’s interview)

In contrast, not all teachers had a thorough knowledge of their students, which will influence their selection of materials and thereby hinder students’ learning. For instance, Betty’s Activity 4 in Table 3, that is, dictating three idioms, required students’ advanced listening competence and inter- cultural knowledge but received rare responses due to the mismatch between the difficulty of the task and students’ language proficiency. Betty attributed her failure to enacting this activity to her students’ low language proficiency level, as the extract illustrates:

The students are all majoring in the arts. Their English language proficiency level is much lower than their cohorts. (Betty’ post- lesson interview)

Thus, teachers’ knowledge of students’ language proficiency, interests, and needs play a crucial role in their evaluation and adaptation of the materials.

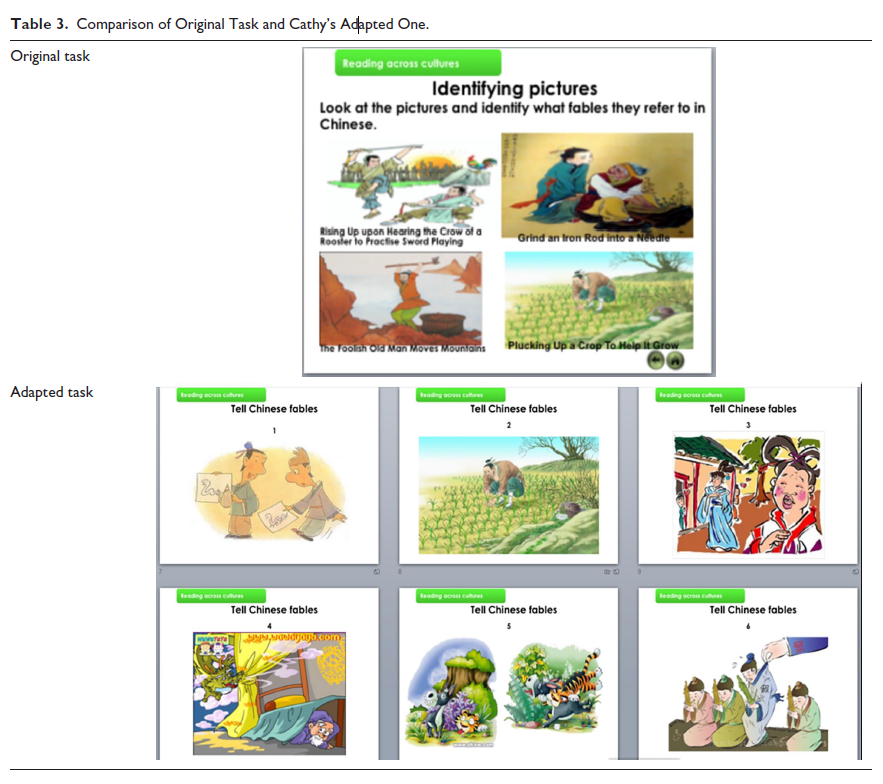

Modifying the given instructions. Teachers not only substituted the textbooks with teacher-designed materials but they also expanded or veered from the original pedagogical intentions of the given materials. For instance, Cathy revised the given translation exercise into an oral task (see Table 3).

The adapted task was different from the original one in terms of pedagogical focuses. Although the original task was designed to test students’ English-to-Chinese translation skill, as shown in the instruction, the adapted one was more concerned with cultivating students’ oracy as indi- cated in revised instruction “Tell Chinese fables (in English).” Clearly, the given materials enlightened Cathy for this adaptation in terms of content. At the same time, Cathy’s agency of promoting communicative learning was also witnessed:

If the activities suggested in the textbook are boring, I will replace them by searching for more authentic and communicative materials online, which was very time-consuming. (Cathy’s pre-lesson interview)

In this sense, teachers are not conduits of the prescribed text- books, but active developers and learners through the use of materials.

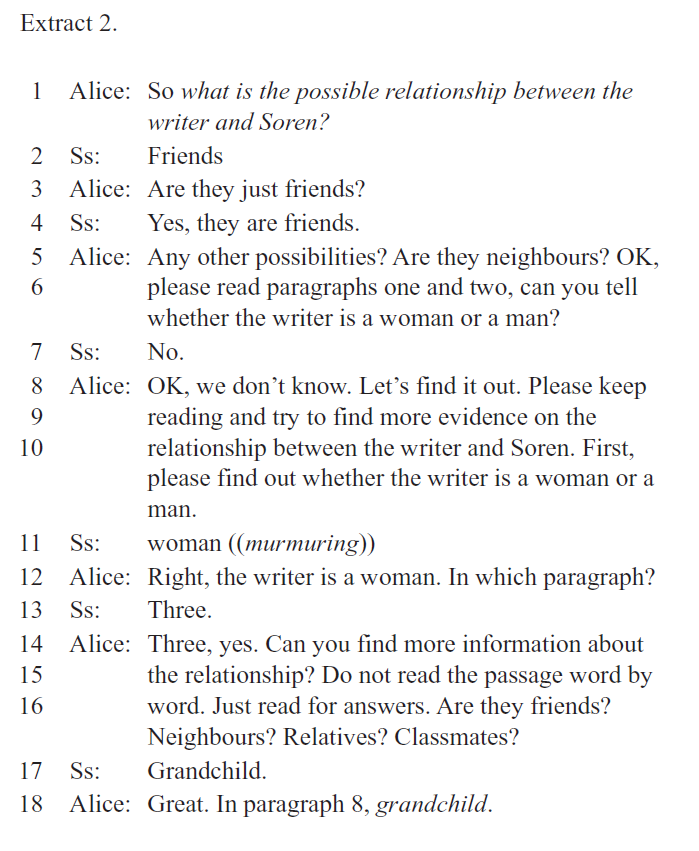

It is worth mentioning that teachers’ autonomy in adapting materials was constrained due to the primary and secondary levels of the textbook. First, the features of curriculum materials confined teachers’ use of certain materials. For instance, it was witnessed that in most cases, teachers’ instruction was heavily reliant on the content of the textbook. Teachers merely transformed the modality of the materials from written texts into verbal interactions. For instance, Table 4 shows how three teacher participants enacted the same exercise (see Figure 1).

As shown above, three teachers’ enactment of this information-gap exercise was highly similar to each other in terms of the patterns of teacher–student interaction.

Second, teachers’ perceptions of the prescribed textbooks indicated the authoritative role of textbooks in their teaching, as the excerpts illustrate:

We could not bring students some materials just according to our preferences. There is a system in providing teaching materials. (Betty’s pre-lesson interview)

Even if I could use other materials, my students believe textbooks should be the only resources for their learning. (Cathy’s pre-lesson interview)

Students’ views on the prescribed textbooks resonated with their teachers in terms of the irreducible and authoritative role of textbooks in their learning, as the excerpts show:

If we didn’t have textbooks, English class would become meaningless and we might have nothing to do during class. (Betty’s male student’s interview)

They (the textbooks) provide the directions for my language learning. If there were no textbooks in class, I couldn’t guarantee I could mesmerise teacher’s instructions. I may feel I didn’t learn anything from her class. (Betty’s female student’s interview)

Our textbooks are penetrating in the whole two-year CE course and play a systematic role in this compulsory course. (Cathy’s female student’s interview)

In other words, the textbooks represent the de facto curriculum and essential teaching content in this nationalized curriculum context, and the agency of the materials was thereby exercised through the representations of the textbook.

Improvising

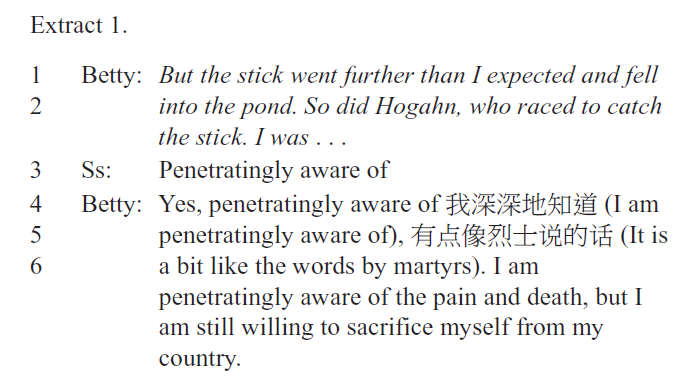

Teachers’ improvisation was represented in the acts of inserting new knowledge or scaffolding. For instance, Betty’s improvisation was afforded by the given material, stretched from her knowledge base, and triggered by the emergent interaction with students. Her partial use of materials is shown in Extract 1:

When letting her students to fill in the blanks using the phrase, that is, penetratingly aware of, Betty inserted a sample sentence (in Lines 5 and 6). It was not drawn from the passage or any other curriculum materials but was from Betty’s own knowledge base.

Meanwhile, teachers need to deploy assemblage of knowledge to insert scaffolding. For instance, Alice used her knowledge about the text, knowledge of students’ comprehension, and knowledge of instructional strategies to build her probing. To facilitate students to answer the question (e.g., what is the possible relationship between the writer and Soren?), Alice modified the original question into a series of yes–no questions (see Lines 3, 5, and 6 in Extract 2). Students’ correct responses (Lines 11, 13, and 17) demonstrated their better understanding of the text due to Alice’s scaffolding:

Betty’s and Alice’s improvisations were not merely derived from the materials, but co-constructed by teachers’ knowledge, students’ reactions, and the affordances of the materials jointly. This process of improvising had a much higher requirement of teachers’ contingency as students’ reactions were not always in line with teachers’ expectations. If the contradictions happened, teachers might modify their previous schemes of materials use and simultaneously evalu- ate the appropriacy of the adapted approaches.

Reflecting and Reconceiving

Teachers would also reflect on unanticipated learning outcomes by either consulting to more knowledgeable colleagues for good practices or referring to online resources and reconceive the potential pedagogical knowledge in the materials during or after class. For instance, Cathy’s awareness of the misleading role of a given instruction stemmed from enacting a reading activity. In this reading activity, the intended objective was to cultivate students’ reading skill of prediction. At first, Cathy followed the printed instruction (i.e., read the blurb of the novel and answer the following questions) and let her students read the passage and discuss the experiences of the author. To her great surprise, most of the students read the passage aloud without using any predic- tion skills, which were not in line with the pedagogical goal. She then explicitly elaborated on the intention of the task and asked her students to predict what would happen to the author based on their own experiences and common sense. This time, her students successfully finished the task, as this extract elucidates:

I just taught predicting and let them read the blurb of AC2. I told them there was a blurb, which is the brief introduction of the novel. I asked them to read the blurb and answer the following questions, for example, when the author first came to the U.S., what kind of problems he might meet? The result is . . . my Student . . . actually borrowed his answer from the passage directly. I told them to throw the passage away, not to read the passage first, and think about the questions . . . So in the second class, I had to point out emphatically that not to read the passage and put it away. In this way, the effect was much better. (Cathy’s post-lesson interview)

The dramatic differences of students’ responses before and after Cathy’s deliberate adaptation of the given instruction triggered her reflection on the enactment of the instruction. By drawing on her new knowledge of enacting the instruction, she refined her original instructional strategies. The process of reflection drove the growth of her knowledge and let her reconceive the pedagogical meaning of the same material.

Teachers’ reconceiving process was stimulated not only by self-reflections but also by consulting more knowledgeable colleagues or referring to more information-rich and appropriate materials. For instance, as mentioned earlier, due to the opacity of pedagogy represented in the textbook, teachers searched the internet for more relevant information or consulted experts in some certain fields to enact the mate- rials more effectively. For instance, Betty learned from Alice about how to adapt a vocabulary exercise into a story-telling oral practice. Alice drew on online resources to supplement a series of lead-in games. In this sense, teachers’ changes in using the same materials at different points evidenced the developmental character of teacher knowledge deployed in the process of materials use.

In sum, there are six interactive processes via which teachers used materials at classroom settings. Figure 2 shows the map.

Discussion

The findings demonstrate that teachers underwent six inter- active processes of materials use at the classroom level: that is, identifying, evaluating, adapting, improvising, reflecting, and reconceiving. The processes of materials use concur with Ball’s (2012) conclusions that teachers’ enactment of materials is interpretive, dynamic, and interactive. Teachers, students, and materials are all participating in the whole process of transforming the institutional curriculum into the class- room curriculum in a specific educational context (Deng, 2017). Accounting for materials use requires attention to both cognition and practice as an individual and sociocultural phenomenon.

The Dialectics of Knowledge and Practice in Materials Use

Through the lens of Keller and Keller’s (1996) anthropology of knowledge, teacher’s practice of materials use is characterized by a dialectic relationship between knowledge and practice which are each continually derived from and altered by the other. First, the whole process of materials use entails cognitive anticipation (i.e., conceptual plans for using mate- rials) and material accomplishment (i.e., adapted materials and improvised instructions). To enact conceptual plans of materials use, teachers need to draw on an array of personal resources, particularly the stock of knowledge, including knowledge of content, knowledge about the text, knowledge of students, and knowledge of instructional strategies. They then formulate a series of constellations, including pedagogical goals, instructional approaches, and selections of feasible materials, to ensure the accomplishment of teaching plans.

Second, this ordinary work of materials use is, in its essence, always creative, innovative, and flexible, where teacher knowledge is highly demanded. Fulfillment of each process required a range of teacher knowledge. For instance, in the improvising process, the inserted extra knowledge input and scaffolding illustrated key dimensions of teacher knowledge. Betty demonstrated her knowledge base of the target language when improvising a sample sentence to enrich students’ vocabulary base. Alice’s inserted scaffolding required her contingency and accurate knowledge of students. In this light, the process of improvising has a higher demand for teacher knowledge than following the scripts of the written materials, as shown in teachers’ rigid enactment of the sentence-completing exercise. It is heavily dependent on teachers’ contributions in terms of broader content knowledge, knowledge of instructional strategies, knowledge about language, and knowledge of students. The limitation of teacher knowledge will certainly impinge their practice. In this sense, the varied mode of responses that different teachers formulated toward the same artifacts might hinge on the divergent knowledge bases of the actors.

Third, teachers’ informed reflections on materials use will feed back into their original knowledge repertoire and provide potential opportunities for teacher learning. In this study, teacher learning occurs in the processes of adaptation, improvisation, reflection, and reconceiving. When the students’ responses or reactions are beyond teachers’ expectations, new constellations must be formulated to meet the desired goals of each teaching plan. As witnessed in the process of reconceiving, the actualization of each plan could enrich teachers’ current stock of knowledge and facilitate the construction of the next constellation. The process evolves until teachers’ pedagogical goals are reached.

In sum, teachers’ cognitive process is central to this productive social activity of materials use. In the cognitive process, teachers’ pedagogical goals governed their pedagogical and curricular decisions on materials use (Keller & Keller, 1996). The constellations consisted of the foundation of materials use. Most importantly, the stock of knowledge was dialectical to teachers’ practice of materials use, which have implications for teacher learning through materials use.

Multilayered Roles of Artifacts

The inconsistencies of textbook use by teachers may result from the discrepancies between representations of artifacts and enactment of them. Findings revealed that the affordances and constraints of the same materials were manifested at primary (pragmatic), secondary (epistemic), and tertiary (heuristic) levels. At the pragmatic level, the materials facilitated teachers’ teaching and students’ learning in terms of providing teaching and learning content. For instance, most of the teachers’ adapted activities stemmed from the textbook and auxiliary PowerPoint slides that were witnessed as indispensable in teachers’ daily teaching and students’ learning in this educational context. According to Wartofsky (1979) and Van Lier (2004), artifact also has its epistemic value. At the epistemic level, teachers perceived the potential pedagogical knowledge deposited in the textbook to design and enact instructions in class. Teachers’ interpretation of the materials might be in line with or opposite to the designers’ intentions. This again indicated the dynamic and complex character of teacher–text relationship in that both teachers and textbooks exercise agencies of defining the classroom- level curriculum. Wartofsky’s notion of tertiary artifacts touches on how a representation of an artifact might become part of a person’s way of acting and thinking (Habib & Wittek, 2007). At the heuristic level, the findings of this study revealed that the prescribed textbooks denoted the power and authority in the nationalized curriculum context. On one hand, the embodiment of textbook enabled policy- makers to impose curriculum reforms through changing text- books in China (Wang, 2007). However, according to this study and previous literature (see, for example, Brown, 2009; Remillard & Heck, 2014), it was incapable of reaching innovative teaching outcomes merely through the change of teaching instruments because materials use is dynamic, complex, and context-driven. This context-specific factor in higher education in China—meaning that every teacher has to use the same textbooks, follow the set syllabus, and cover the same units in each academic year—was not always facilitating in the educational change if teachers’ agentive power was neglected. On the other hand, teachers developed conceptual plans in attending to textbooks over time because of the irreducible role of textbooks in ELT in China. The for- mation of Betty’s conceptual plan conceived from the text- books demonstrated the development of her curriculum thinking or curriculum literacy (Steiner, 2018). In other words, the artifacts are sociocultural devices that will influence our cognitive functioning (Vygotsky, 1978). We believe that these dimensions of affordances in an artifact are particularly crucial for teacher learning through materials use and development.

Implications and Conclusion

In sum, this study unraveled how language teachers use text-books in classroom settings from an interdisciplinary perspective. All teaching materials carried meanings, including the representations about their usage. What varied was the mode of response, which depended on the capacity and knowledge composition of the users (McDonald et al., 2005). The dynamic, interactive, complex, and multilayered relationship between teachers and materials suggested the possible ways of engaging, enlightening, and empowering language teachers through the in-service professional development and materials development.

For inservice professional development, it is essential to foster teachers’ knowledge concerning materials use. The competence of making effective use of materials can be fostered at instructional, institutional, and national levels. At the instructional level, teachers need to continually enrich and enhance their knowledge base in terms of language, students, and pedagogy through reflecting and learning from their use of the same materials in different classes. At the institutional and national levels, it is suggested that publishing houses or institutions organize professional development activities to exchange best ways of materials use among teachers who are using the same materials. Collegial cooperation can be another model for inservice professional development concerning materials use (Bouckaert & Kools, 2018; Humphries, 2014). The professional development should be oriented toward how to develop teachers’ personal practical knowledge concerning materials use. Publishing houses are expected to promote new teaching beliefs and pedagogy intended by the curriculum developers through teaching training activities, such as national teaching contexts (Xu, 2017).

For materials development, materials need to be diversified in terms of modality and content and be made transparent in terms of pedagogical foci. Given that teachers’ use of materials was closely related to the nature and design of the materials, it is imperative for material developers to create more multimodal and flexible materials to support teachers’ daily work because all resources have the potential to work together as an assemblage for meaning-making (Canagarajah, 2018). Moreover, materials should have more room for teachers to authenticate under different circumstances (Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2018). In other words, materials should be developed as intellectually engaging and meaningful to their users. The pedagogical representation embedded in the materials could be more direct, explicit, and concrete to cater to teachers’ various needs (Remillard & Kim, 2017). Educative materials to advocate innovative pedagogy with teachers as the audience could also be developed (Davis et al., 2017) because materials as artifacts have the agency to change and modify human cognition through multilayered affordances (Radford, 2012). The process of mate- rial use is intertwined with the process of teacher learning (Grossman & Thompson, 2008; Reisman & Fogo, 2016). Thus, materials use and development are arguably the most convenient ways of fostering teacher learning as every teacher is a material user (Tomlinson, 2018).

How teachers bridge the gap between the materials and the students lies at the heart of effective materials use. The findings reminded us that both the content and format of materials could be tailored to match each classroom’s ecology. The interfaces between the content of the materials and students’ needs could offer great opportunities for teachers to creatively contextualize the materials. For instance, the selection of materials could be deliberative by taking students’ interests, majors, and language competence into con- sideration (Li, 2020). In addition, the format of materials could also be changed to cater to students’ needs. For exam- ple, because students in China were more concerned with the exams, such as how to attend to authentic exam exercises, teachers could adapt the given exercises in line with the authentic exams. The knowledge of students and context is crucial for authenticating materials.

Furthermore, the study also opens up new avenues for future research on materials use in terms of theoretical underpinnings and research design in divergent educational con- texts. Because artifacts are artificial devices, neither the understanding of the pragmatic use of materials nor the best exploitation of their epistemic and heuristic possibilities is self-evident (Radford, 2012). This coincides with Norman’s (2013) concern that the intended affordances of artifacts will not be correctly perceived by the users. Therefore, investigating artifact use in natural educational settings is becoming increasingly urgent and necessary. We suggest that more holistic theoretical perspectives and frameworks are employed to examine the issue by treating materials use as a social, institutional, and instructional phenomenon (Deng, 2017). Although educational contexts will be strikingly divergent, the concept of best exploiting of the pragmatic, epistemic, and heuristic possibilities of artifacts is neither context-nor discipline-specific. Investigating the proper condition of artifact use in global educational settings will surely bring us more insights into how to change the rigidity of materials use into an engaging, enriching and empowering experience for teachers all around the world.

注:本文选自Original Research 1–13。由于篇幅所限,注释和参考文献已省略。