Introduction

Task-based language teaching is gaining in popularity not only in the literature on second language acquisition (SLA) but with teachers and students too. The strong version of task-based language teaching (TBLT) advocates setting students a meaning-based task with a non-linguistic outcome (e.g. making a paper airplane; inventing a device for saving water; devising and giving instructions for a game; recommending which sports should be taught in the school). Although the main objective of the students is to achieve the outcome of the task the teacher might have language learning objectives in mind (e.g. improving the students’ ability to give clear instructions) and the teacher will typically help the students with language problems they encounter in performing the task as well as lead a reflection stage on the task performance of the students after task completion. Ideally there will also be language input (e.g. a stimulus text; spoken and/or written instructions for the task) and language output (e.g. student discussion during performance of the task; student written or spoken presentation of the task outcome). The main SLA principles on which this approach is based are student experience of contextualised and authentic use of language (i.e. to achieve a communicative outcome as opposed to focused practice of a structure), being stimulated and pushed by interaction, learning from doing, learning from a teacher when the learning is needed and wanted and being cognitively engaged. The weak taskbased approach is similar but includes pre-teaching of the language required in the task and possibly postteaching of language points too.

For information about TBLT see Long (2015), Mackey, Ziegler & Bryfonski (2016), Tomlinson (2015) and Van den Branden (2006) and for accounts of how TBLT approaches have been weakened by teachers in order to prepare their students for examinations see Thomas & Reinders (2015).

Text-driven approaches to materials development for language learning are those in which units of materials are driven by potentially engaging written spoken or visual texts rather than by pre-selected teaching points. The objective is to engage learners affectively and cognitively (i.e. to stimulate them to feel and think) through experiencing and responding personally to the text prior to using it to drive production activities and as a basis for discovery activities. The underlying principles include exposure to language in use, affective and cognitive engagement, use of language for communication and opportunities for learner discovery. For information about text-driven approaches see Tomlinson (2015) and Tomlinson & Masuhara (2018).

A Problem

One of the experts on TBLT referred to above is Michael Long, an applied linguist who has made a valuable contribution to the field of SLA and who I have respected for many years. Long (2015) not only summarises what has been said in the literature and done in the classroom with regards to TBLT but he also manages to apply theory to practice in feasible and potentially effective ways. I agree with and value just about everything he says in the book except for his rejection of the role of texts in TBLT in 2015, p. 305.

On p. 305 Long says, for example, ‘Use task not text, as the unit of analysis’. In my view, if you rely on task as the unit of analysis and do not make use of engaging texts to stimulate responses and generate tasks, you can end up with an obvious but incomplete syllabus of asking for directions, ordering a meal, spotting the difference between two pictures, telling the story of a picture to a partner and other rather trivial speech events with some potential utility but little cognitive challenge or engagement. These are the sort of tasks which have been used by researchers to evaluate the effectiveness of tasks. They are ideal for research because they make it easy to control and to assess task performance but they are far from ideal for classroom use as their lack of stimulating content and of cognitive challenge can make them very unappealing to intelligent learners.

Long (2015, p. 305) also says, ‘the focus in text-based courses […] is language as object’. This might be true of some text-based courses but the focus in text-based courses obviously does not have to be on language as an object, it can be on the holistic meaning of the text, on the intentions of the writer or speaker or on the responses of the learners to the text. It can also be on the way that language is used to achieve intended effects and therefore on language as an affordance of communication rather than language as an object. In addition, Long does not differentiate between text-based approaches, which do ultimately focus on the language of texts, and text-driven approaches (Tomlinson, 2013) which make use of potentially engaging texts to drive receptive and productive tasks.

Another example of Long’s attack on texts is his statement that, ‘Texts are frozen records, often unrealistic records, of task accomplishment by others, i.e. a by-product of tasks’ (2015, p. 35). Texts do not have to be frozen or unrealistic. They can be alive and authentic, even at lower levels, they can bring the target language to life by relating it to the real world, they can stimulate interaction between the producer of the text and its recipients as well as between the recipients, and they can lead to authentic communication by learners who experience the texts.

I find it quite remarkable that Long does not discuss the potentially positive roles of texts in TBLT and that he gives the impression on p. 305 that texts have no positive role to play in TBLT (even though there are some texts in his very useful examples of tasks at higher levels in his 2015 book). I have read numerous dissertations and theses in which students have said that Long disapproves of using texts in TBLT and therefore the students do not use texts in their often trivial tasks (usually the spot-the-difference or the picture story tasks which they have encountered in the books and articles they have read on TBLT). As a result the students they are conducting their research on (and those they subsequently teach) are denied the potential stimulus and the vital exposure to language in use which texts can provide.

A Proposal for a Text-Driven Task-Based Approach

To redress the balance I would like to propose and exemplify a text-driven (not text-based) approach to task-based teaching and to claim that using texts to drive tasks in units of material can:

• increase the students’ affective engagement (by, forexample, stimulating them to laugh, to cry, to feel exhilarated, disturbed, excited, sad, sympathetic or angry).

• increase the students’ cognitive engagement (by,for example, stimulating them to think in order to connect the text to their lives, to comprehend the full significance of the text, to evaluate ideas put forward in the text or to solve a problem posed by the text).

• increase the content value of the unit (by addinginformation, ideas and experienceto what otherwise might be a shallow experience of the target language).

• increase the educational value of the unit (byproviding a new experience to connect to and possibly learn from).

• stimulate more ‘authentic’ tasks (which relate towhat the learners are interested in and to what they want and need to do with the target language).

• stimulate valuable tasks which might not beincluded in a needs driven task syllabus.

• ensure the students receive a rich and meaningfulexposure to language in use.

Simple examples of such text-driven tasks would be:

1. for groups of students to be given three comics in the L2 to look through before deciding which one they want the class library to subscribe to and then giving a short presentation to support their recommendation.

2. for the teacher to perform a dramatic reading of a poem or short story and for the students to then make a video film of it (as I once did in a language school where the students read and responded to the poem The Schoolmaster by Yevtushenko before making a video of their interpretation of it).

3. for students to read a harrowing text about the extreme effects of a water shortage and then to design a cheaply-made device for saving water and sell it to an international company in a letter and a presentation.

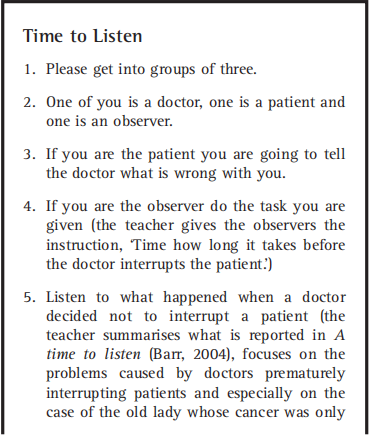

Here is an example of a unit of ESP materials in which a task is driven by a text. This task is unlikely to have emerged from an analysis of the needs of non-native speaking doctors, nurses and medical students who are the target learners for the unit.

This unit of material follows a flexible procedure for developing text-driven tasks for the classroom:

1. A readiness activity to activate the learners’ minds in relation to the theme, topic or location of the text and task (e.g. a visualisation activity, a connecting to previous experience activity, a prediction activity, a mini-role play).

2. An experience of a potentially engaging text which focuses the students’ minds on the meaning of the text rather than on the language it uses to express the meaning (e.g. a visualisation activity, a continuation of a connection readiness activity, a checking of predictions activity, an inner speech questioning of the author/speaker) .

3. A personal response to the experience of the text which helps the students to deepen and articulate their interpretation and reaction to the text (e.g. drawing what comes to mind when they think back to the text, saying what they like/dislike about the text, responding to a provocative statement about the text, summarising the essence of the text for someone who hasn’t experienced it).

4. A task driven by the text (e.g. an oral presentation of views, a letter to the author/speaker of the text, a continuation of the text, a modified use of the text, the presentation of an invention inspired by the text, the presentation of a solution to a problem posed in the text).

5. Peer monitoring of the task performance by individuals or groups of students with a view to offering advice both on the content and the expression of the task performance.

6. Comparison with a proficient user of the L2’s performance of the task – preferably focusing on a particularly salient lexical, structural or pragmatic feature of the text.

7. Task revision (or performance of a different but similar task).

8. Research Task (looking for ‘texts’ outside the classroom which provide further evidence of how language features investigated in 6 are typically used).

For more detail and examples of text-driven approaches see Tomlinson, 2013. Please note:

1. Not every stage of this framework needs to be used in a unit of material and stages 5-8 can be used in different sequences (for example, with the research task conducted before the task revision).

2. The teacher is encouraged to teach responsively in stage 4 by providing help and advice when invited.

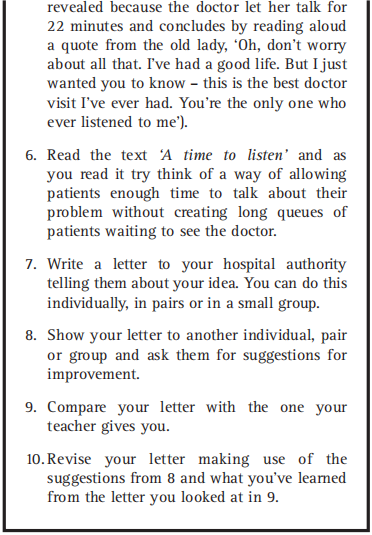

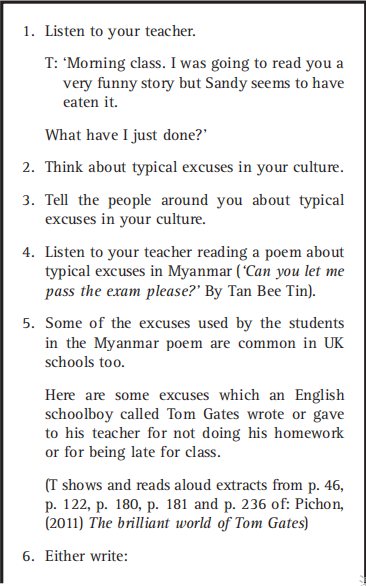

Here is another example of a text-driven task-based unit of material, this time for General English students:

Conclusion

Task-based approaches to language learning are not new. I have been using them since the 1970s and I even published a collection of tasks written by myself and a group of teachers (Tomlinson,1981) to be used in both the classroom and the examinations in primary schools in Vanuatu. What I found then and have found ever since in classrooms, for example, in Japan, Oman and the UK is that using potentially engaging texts to drive tasks is far more productive than simply setting students a task. I have seen students bored and off task doing spot-the-difference and picture story tasks and I have frequently seen students come alive in English when doing tasks whilst still stimulated by an engaging text. It would be interesting to compare the difference in attitude and performance of an experimental group doing a task driven by an engaging text and a control group doing the same task without the text to stimulate them first.

注:由于篇幅所限,注释及参考文献已省略。