Language learning and teaching (LLT) materials—like teacher-created handouts, textbooks, and over-head transparencies—are central elements of language classrooms worldwide. Nonetheless, how language students and teachers actually engage with and deploy LLT materials has rarely been the focus of research. In response, this issue offers the first compilation of classroom-based studies of ‘materials use’ in language education and includes research on Ojibwe, Japanese, French, and English language pedagogy. In this introductory article to the special issue, we set the stage for the 7 empirical articles by offering much-needed definitions for the concepts of ‘LLT materials’ and ‘materials use.’ These definitions are based on a metasynthesis (i.e., an integrative qualitative analysis) of all of the materials used throughout the 7 empirical articles. Additionally, we explore sociomaterialism as a compelling and well- suited framework for the study of materials in use. Sociomaterialism is not a unified theory but rather a research orientation that seeks to examine connections between the social and the material world. In addition to substantively and theoretically advancing the field, all the articles of this special issue also have practical implications for language pedagogy.

Keywords: materials use; language learning and teaching; sociomaterialism; intra-action; classroom-based research

IN RECENT YEARS, EMPIRICAL INQUIRY into how materials are used in language learning settings like classrooms has emerged as a “ground- breaking” area of research (Tarone, 2014, p. 653). Nonetheless, this field is still understudied, undertheorized, and poorly understood in general (Guerrettaz & Johnston, 2013; Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2018). These conditions are likely tied to the lack of adequate definitions around this key element of language teaching and learning— namely, materials. It may be surprising to real- ize that language education researchers do not have an empirically based definition of ‘language learning and teaching materials’ (LLT materials). As a much-needed response, in this introductory article we offer working definitions of ‘LLT mate- rials’ and the related concept of ‘materials use.’ Any robust definition of materials should involve observational, empirically based research of mate-rials use and come from studies in a wide range of contexts. This issue includes seven studies on the teaching and learning of four languages (Ojibwe, Japanese, French, and English), and the definitions presented in this introductory article draw on all of these studies.

Rather problematically, previous definitions of ‘materials’ (e.g., Tomlinson, 2018) are not typically based on studies of materials in language learning settings.1 Perhaps for this reason, existing definitions tend to (a) overlook the complexities of materials, including how they affect language learners and teachers, language pedagogy, and language use, and (b) focus on limited types of materials—namely, textbooks. The diversity of materials that language teachers and learners actually employ in classrooms goes beyond such narrow conceptualizations, as this guest- edited issue illustrates by examining materials as diverse as films, cell phone apps, objects found in nature, a teacher’s makeshift jigsaw activities, and more. Specifically, this introductory article offers a metasynthesis of the issue’s seven empirical articles—meaning, an integrative and qualitative analysis of their findings. This is the basis of the definitions we present for (a) ‘LLT materials,’ and (b) ‘materials use’ in LLT (henceforth ‘materials use’).

This issue also serves as the first ‘collection’ that primarily focuses on materials use in language teaching and learning. Similar to inquiry on objects from the social sciences more broadly (Nevile et al., 2014), materials have rarely taken center stage in language classroom research,2 which tends to focus on human actions and linguistic systems rather than nonhuman, mate- rial aspects (Canagarajah, 2018a). In contrast, we argue that the material world is integral to LLT. Thus, this issue contributes to the materi- alist turn in language education (Canagarajah, 2018a; Pennycook, 2018; Toohey, 2019). Specifically, ‘sociomaterialism’ (e.g., Fenwick, 2015) ties this issue’s studies together as an overarching research orientation.

By definition, sociomaterialism breaks down artificial boundaries between the material and the social, by foregrounding entangled interrelation- ships of the material world in relation to social processes, structures, and dynamics. Sociomaterial approaches enable researchers to identify “patterns of materiality” in social interaction, education, and learning while simultaneously accounting for the oftentimes unpredictable dynamism of classrooms (Fenwick, Edwards, & Sawchuk, 2011, p. vii). Sociomaterialism is not a single, unified theory but rather an orientation that is increasingly present in diverse educational and social science frameworks. Although this issue’s studies employ different theories and methodologies, they all connect broadly with sociomaterialism. Moreover, all of these articles focus on materials use in classroom contexts, thereby addressing micro-level (e.g., discursive, interactional) and macro-level (e.g., overarching community cultures, power dynamics) contextual matters.3 As will be shown, such classroom-based empirical approaches and their underlying epistemologies have long been lacking in LLT materials research.

Furthermore, this guest-edited issue on materials use has clear pedagogical implications. Language educators can benefit from increased understanding of the material elements that influence the classroom and their learners, for example, by considering how materials can limit or enhance possibilities for meaningful and effective learning and teaching. Sociomaterial orientations can also shift instructional approaches away from teaching methods that seek predictability and control toward pedagogies that are responsive to the emergent, unpredictable nature of LLT.

RESEARCH ON LANGUAGE LEARNING AND TEACHING MATERIALS IN USE

As with any field, the definitions that are used to frame research on LLT materials use are integral to the advancement of the discipline itself. Importantly, existing definitions of ‘LLT materials’ and ‘materials use’ tend to be vague and, in many instances, overly focused on the out-of- classroom development of materials. In a recent book, Tomlinson and Masuhara (2018) defined materials as “anything [emphasis added] that can be used by language learners to facilitate their learning” (p. 2). Similarly, Guerrettaz and Johnston (2013) described materials as “any artifacts [emphasis added] that prompt the learning and use of language in the language classroom” (p. 779). These definitions suggest that LLT materials comprise a much greater diversity of entities than textbooks alone, which is the narrow focus of most existing LLT materials research. Moreover, though these definitions allow for many ‘kinds’ of materials, such vague descriptions of materials as “anything” (Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2018) or “any artifact” (Guerrettaz & Johnston, 2013) leave researchers in need of more concrete and exact- ing language and constructs for different types of materials. Empirical research of materials in classrooms is necessary to generate such analytically powerful, precise, and comprehensive definitions.

A slightly more specific definition from Mishan and Timmis (2015) asserts that, “the defining characteristic of materials is that the materials designer builds on a pedagogic purpose” (pp. 2–3). Mishan and Timmis’s focus is the a priori design and intentions surrounding materials rather than the context in which the materials are used, including the teachers, learners, and classroom. Yet these latter elements are as integral to the appropriateness, effectiveness, and ‘identity’ of a mate- rial (i.e., its salient qualities and affordances) as the a priori design, if not more so.

The field also struggles to define the related concept at the heart of this issue, ‘materials use’— though a few definitions have been proposed. Decades ago, Hutchinson’s (1996) unpublished thesis described materials use as a “dynamic and complex interaction of the teacher, learners and the textbook itself (…) influenced by a number of factors” (p. ii). More recently, a community of materials use scholars, MUSE International, proposed another definition: “At the root of materials use lies action [emphasis added] associated with and influenced by materials” (Grandon, 2018, p. 42, as cited in Guerrettaz et al., 2018, p. 38). Matsumoto (2019) defined ‘materials use’ as “the ways that participants in language learning environments actually employ and interact with materials” (p. 179). Both recent definitions of ‘materials use’ come from empirical research and underscore ‘interaction and action’ with LLT materials, though the nature of these remains un- clear. Furthermore, these vague definitions fail to address other dimensions and complex phenom- ena that materials use seemingly involves. The definitions of ‘LLT materials’ and ‘materials use’ both need to be developed through empirical inquiry so that researchers can adopt these and advance scholarship of materials across different contexts.

This lack of adequate definitions may be due to the fact that research that examines materials in use as its central focus is relatively new to the field of language education. Some research— particularly multimodal classroom discourse analyses or studies on language learning ecologies— may integrate LLT materials or other classroom objects as part of data collection or analysis. How- ever, this research typically stops short of study- ing materials as a primary object of inquiry (e.g., Hellermann, Thorne, & Fodor, 2017; Levine, 2020; cf. Guerrettaz & Johnston, 2013; Jakonen, 2015; Matsumoto, 2019).

Moreover, two tendencies delimit applied linguistics’ current conceptualization of LLT materials. The first tendency is to treat materials as a background ‘contextual’ issue in classroom- based studies (e.g., Majlesi, 2018, on corrective feedback; Ohta, 2017, on learning linguistic honorifics; Seo, 2011, on repair sequences; see Matsumoto, 2019, for a review). We contend that the field “need[s] a [new] definition of context,” bringing that which has previously been dismissed as “background to the foreground” (Levine, 2020, p. 21). Such overlooked issues (e.g., materials) of- ten actually form part of the ‘core’ of language pedagogy. The second tendency is to treat materials merely as representatives of human ends. As Waltz (2006) observed, materials—by which he meant nonhuman objects—are often analytically subsumed by human intention and actions. This second tendency oversimplifies the roles that ma- terials play in LLT contexts.

Guerrettaz & Johnston’s (2013) study of a grammar textbook in use in English language teaching (ELT) (a) problematized this lack of research on materials use, especially compared to the abundance of publications on ‘materials development and evaluation’ (cf. Canagarajah, 1993; Harwood, 2014) and (b) called for more empirical inquiry on materials use in language classroom interaction. Responding to Guerrettaz & Johnston, a Perspectives column in The Modern Language Journal (e.g., Larsen–Freeman, 2014; Tarone, 2014) highlighted the significance of this research on materials use as an emergent field of inquiry. In that landmark column, several contributors (Garton & Graves, 2014; Morgan & Martin, 2014) also discussed the necessity of materials use inquiry for advancing language teaching practice, teacher education, and materials development.

A handful of recent classroom-based studies of LLT materials (e.g., Matsumoto, 2019; Pourhaji, Alavi, & Karimpour, 2016) have responded to these calls. However, most existing studies on ma- terials use have narrowly focused on textbooks and ELT (e.g., Canagarajah, 1993; Guerrettaz & Johnston, 2013; Opoku–Amankwa, 2010), thus necessitating a conceptual expansion regarding what counts as LLT materials—beyond textbooks (although see Harwood, 2021). Moreover, the emphasis on ELT represents another problematic gap in the literature that this guest edited issue attends to by examining a diversity of languages in relation to LLT materials in use.

These few previous publications on materials use suggest that LLT materials can paradoxically induce both predictable and unexpected patterns of classroom interaction and activity, pointing to the complexity of materials use. Importantly, classroom-based research on materials in use provides critical insights into the modus operandi of language learning contexts.

Similar to that small body of existing scholarship, the studies of this issue are rooted in classroom-based, observational, and interactionist approaches and employ discourse analytic, ethnographic, ethnomethodological, and participatory research methods. This overarching tradition of classroom-based research has strongly influenced the field for decades, as it often seeks to understand the complexities of language pedagogy by studying naturally occurring interactions and activities. (For example, de Bot’s, [2015] history of applied linguistics points to numerous influential works by Canagarajah, Duff, Kramsch, Kumaravadivelu, Norton, and van Lier, among other classroom-based researchers.) Such scholarship focuses on contextual considerations and represents an impactful overarching epistemological orientation in language education research.

However, this important epistemological orientation and prominent body of classroom-based scholarship does not appear to have significantly affected the study of LLT materials (cf. Gray, 2013; Harwood, 2014). For example, in Tomlinson’s (2013) book about materials development, the chapter entitled “Classroom Research of Language Classes” makes no mention of some of the most influential classroom-oriented scholar- ship in language education. Similarly, a more re- cent book called The Complete Guide to the Theory and Practice of Materials Development for Language Learning (Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2018) aligns it- self more with second language acquisition (SLA) scholars and psycholinguistic paradigms than with approaches rooted in classroom-centered inquiry. Moreover, phenomena that classroom-based and interactionist researchers often study appear infrequently in publications on materials development and evaluation. These include issues of classroom talk and activity, pedagogical practice, and in-class learning opportunities as well as identity-related and cultural processes manifest in classroom interaction. These gaps in the LLT materials research further confirm how little is known from a data-driven perspective about how materials shape language learning environments like classrooms.

The articles of this issue address this over- sight by considering LLT materials in relation to context, including ‘micro-level’ contextual is- sues at the level of classroom interaction and ‘macro-level’ concerns related to overarching political, cultural, and social dynamics. Regarding the former, almost all of the issue’s studies examine discourse or interaction in detail. As an example, Hasegawa (2021) identifies two simultaneous discursive ‘layers’ that characterize students’ use of semi-scripted pair work prompts: One is the ‘pedagogical-activity layer,’ in which students complete turns and use language prescribed by the materials, and the other is the ‘normative-interaction layer,’ in which they interact in ways that more closely resemble ‘ordinary’ conversations (e.g., joking, helping one another). As an example of macro-level con- textual concerns, Sert & Amri (2021) illustrate how student discussions of racism depicted in film materials involved language-focused learning. Thus, this issue addresses the complexities of the language classroom by studying materials in relation to contextual processes, structures, and agents.

In summary, the main goals of this introductory article are to provide new definitions and frame-works for systematically examining LLT materials and materials use. Considering the small body of language education research that has squarely focused on materials use, this issue as a whole advances this poorly understood area by illustrating the complex interrelationships among materials, language use, and LLT. Furthermore, this introductory article and issue at large engage recent theoretical advancements in the broader field of language education: While not generally focused on LLT materials or materials use, recent studies (e.g., Canagarajah, 2018a; Gourlay, 2015; Penny- cook, 2018) have advanced posthumanist and materialist orientations (Canagarajah, 2018a, 2018b; Toohey, 2019; Toohey et al., 2015), which high-light complex meaning-making processes involv- ing materiality and diverse semiotic resources that shape instructional contexts. This theoretical turn demonstrates a newfound interest in the material world within the field.

SOCIOMATERIALISM

In this section, we examine the materialist turn in language education research, relating it to LLT materials and materials use and focusing on sociomaterialism (Fenwick, 2015; Fenwick et al., 2011; Toohey, 2019; see also Canagarajah, 2018a; Pennycook, 2018). Sociomaterialism is central to the definitions that we present in this article for ‘LLT materials’ and ‘materials use,’ and we see great promise and utility in it as a broad conceptual approach to materials use research. Sociomaterialism is a ‘flexible’ paradigm relevant to a wide range of disciplines and local contexts. It has the potential to disrupt what Pennycook (2018) has described as a problematic state of ‘stasis’ in applied linguistics (see also Douglas Fir Group, 2016; Toohey, 2019). Our sociomaterialist orientation builds on recent scholarship that highlights complex classroom dynamics and interrelationships organized through social (e.g., human) engagements with objects, physical environments, and other nonhuman dimensions of the material world (e.g., Fenwick et al., 2011; Toohey & Dagenais, 2015). Sociomaterialism examines complex patterns of power, affect, cognition, and action that structure the social and the material (Fenwick, 2015). Moreover, sociomaterialism views the simultaneous existence of disorder and apparent chaos on the one hand and organization and patterns on the other as a defining dynamic of social settings, like class- rooms (Fenwick, 2015, p. 2). This makes sociomaterialism well suited for understanding materials use phenomena, which are characterized by some degree of predictable patterns while simultaneously being subject to instability and uncertainty, according to the small body of aforementioned research on the topic (e.g., Guerrettaz & Johnston, 2013; Matsumoto, 2019). For example, while a controlled grammar activity can result in certain foreseeable patterns of classroom discourse in some instances, at other times the very same type of activity text can somewhat surprisingly induce extended conversations (Guerrettaz & Johnston, 2013).

Sociomaterialism is not a single, unified theory but rather draws on numerous theories and ontologies from a wide array of disciplines. Nonetheless, sociomaterialists across theoretical orientations and disciplines share common ‘commitments’ regarding the relationship between the material and the social (Fenwick, 2015), which we explore in this section. In particular, we discuss five sociomaterialist constructs that are central to our guest edited issue: assemblages, entanglements, emergence, intra-actions, and distributed agency.

First, ‘assemblage’ is a complex heterogonous gathering of polysemiotic resources or elements, which are emergent in nature and imbued with histories, ideologies, and other types of meanings (see Fenwick, 2015; Toohey, 2019). These can be material, bodily, spatial, linguistic, technical, ideological, affective, cognitive, and historical in nature. For instance, we can apply this concept to an Arabic language textbook to conceptualize its nature as both material (e.g., a heterogeneous assemblage of paper, cardboard, glue, ink, and printed symbols) and social (e.g., the same heterogeneous assemblage also involving formal learning associations, a standardized variety of Arabic, and a focus on Arabic literacy). Importantly, this textbook exists at all times in a context, relative to other bodies, spaces, discourses, processes, and more. Moreover, the concept of ‘assemblage’ stretches, becoming more complex when we consider our same Arabic language text- book in use. Enfolded into a particular pedagogical context (e.g., on a table in a small group of learners, in the hand of a teacher, or on a book-shelf as an authoritative reference), it is one aspect of a larger, heterogeneous assemblage, which is also social and material in nature.

Within sociomaterialism, terminology around the construct ‘assemblage’ is somewhat unclear. Two commonly used terms include ‘heterogeneous assemblage’ (Fenwick, 2015; McGregor, 2014) and ‘sociomaterial assemblage’ (Bhatt & de Roock, 2013; Toohey & Dagenais, 2015; Toohey et al., 2015). These terminological differences do not apparently distinguish between different types of assemblages but rather serve to highlight the importance of either (a) the multitude of elements that comprise it (i.e., ‘heterogeneous’) or (b) its social and material nature and connections (i.e., ‘sociomaterial’). Both characteristics are inherent to an assemblage. “All materials or, more accurately, all sociomaterial objects, are in fact (…) assemblages” (Fenwick, 2015, p. 5). Fenwick (2015) went on to say that “materials are enacted, not inert” (p. 5). This aligns with our definitions of LLT materials as phenomena that must be un- derstood in terms of both their makeup and con- tent (e.g., what they are) as well as their situated use in context.

The second sociomaterialist concept, ‘entanglement,’ closely relates to the notion of assemblages. Humans and nonhumans are ‘entangled’ in ways which help to explain how all entities, not just people, have the potential to influence situations and shape event trajectories (Fenwick et al., 2011; Toohey & Dagenais, 2015). The concept of ‘entanglement’ is valuable for materials use research because it shifts the focus away from sim- ply examining the composition of an assemblage as if it were simply a knot of discrete elements that could be untangled. Entanglement shifts our focus away from the seemingly separate parts of a given assemblage (e.g., curriculum, teachers, texts) and guides us instead to look at the ever-changing interrelationships among “myriad non-human as well as human elements” (Fenwick, 2015, p. 2). From a sociomaterial perspective, things are already and always entangled (Toohey, 2019), and it is the specific, local entanglements that are important.

Returning to the Arabic textbook example to further explain entanglement: When an LLT material becomes part of a classroom interaction, we cannot presume that the book, the learners, and other salient actors involved therein remain the same henceforth. For instance, a particular reading, video, or discussion prompt can enable student learning in the form of new understandings, a shifting worldview, or increased language abilities. Similarly, the text itself may be altered moving forward (e.g., written upon), or take on new meanings (e.g., for the teacher, students, entire school) as a consequence of the encounter. Even when the physical material is no longer present in that particular classroom, its traces remain entangled with the other entities (e.g., people) that were or are part of it (Sert & Amri, 2021). Sociomaterialism’s embrace of such dynamism is further explicated by the concepts of ‘emergence’ and ‘intra-action.’ In discussing ‘emergence’ and related notions, Levine (2020) explained how considering the totality of a context (e.g., assemblages, entanglement) does not re- quire a simultaneous analysis of ‘everything’ in a classroom setting. Rather, dynamic contingencies in a space can reveal which contextual elements are salient in a given moment, and this potential for significant elements in an assemblage to surface resonates with emergence. From a sociomaterialist perspective, ‘emergence’ refers to the ways that actors, materials, and agency are generated and recognized. The “mutually dependent, mutually constitutive” (Fenwick, 2011, p. 21) nature of these entangled elements means that their identities “do not precede, but rather emerge through, their intra-action” (Barad, 2007, p. 33). ‘Emergence’ refers to the situated nature of not just relationships and structures (Canagarajah, 2018a) but also of material phenomena. This concept also attends to the sociomaterial circumstances that inform how we conceptualize a material in a given moment in time.

Emergence relates closely to our fourth sociomaterialist construct, ‘intra-action.’ Dominant views of education represent humans and non- human materials as subjects and objects that interact with one another—discrete elements that come into contact, perhaps causing action and/or change, but remaining separate. Moreover, in such dominant views, the types of changes induced by such contact and engagement relate to human development, with little consideration for broader transformations vis-à-vis entanglements and the material world (Fenwick, 2015). Sociomaterial approaches, however, are more concerned with ‘intra-actions’ than ‘interactions’ (Barad, 2007), conceptualizing humans, materials, and other entities in a context like a classroom as intrinsically entangled assemblages rather than categorically separate. In this issue, Guerrettaz (2021) focuses squarely on intra-action, defined as “action involving emergent exchanges, influences, or engagements among interrelated entities or beings (e.g., teacher, students, classroom objects)” (p. 41).

Importantly, ‘interaction’ and ‘intra-action’ are both often conceptualized among sociomaterialists as extensions of the construct of ‘action’ (Fenwick et al., 2011), which is also central to previous definitions of materials use (Guerrettaz et al., 2018, following Grandon, 2018). Action can be predicated by human and nonhuman actors (Fenwick et al., 2011, p. 66) and may or may not involve human intention (Sloan, 2010). (For instance, the action of a teenager slamming a door shut in a show of defiance involves strong human intention not apparent in other similar actions, like a gust of wind slamming a door shut or a person doing so unintentionally due to a well-greased hinge.) Action occurs in the social and material world and emerges from a confluence of entangled elements and forces.

Regarding conceptual differences between interaction and intra-action, there is potential for confusion when we study interaction—a central disciplinary construct in language education— within a sociomaterialist paradigm that operates in terms of intra-actions. This dissonance relates to disciplinary gaps. Language education scholars rarely work within sociomaterialist frameworks (cf. Toohey, 2019; Toohey et al., 2015). Instead, the notion of ‘intra-action’ has arisen as an alternative to the construct of ‘interaction’ from other disciplines. Different from language education specialists, most sociomaterialists do not conceptualize ‘interaction’ as primarily linguistic or semiotic but rather in terms of general inter- relationships and exchanges between subjects and objects, an extension in many ways of the notions of ‘mediation’ or ‘affordance’ (e.g., Fenwick, 2015; Garud & Karnøe, 2009). Unlike intra-action, though, mediation and affordance typically conceptualize the material world as secondary, merely in service of human cognition. Moreover, affordance tends to describe the ‘potential’ for learning, while intra-action focuses on occurring and/or observable action, influence, or engagement. Quite different from intra-action, in language education the construct of ‘inter- action’ carries more prominent and complex linguistic meanings, as the site of polysemiotic meaning making and as a sociocognitive process that is crucial to language learners’ development.

We view ‘intra-action’ and ‘interaction’ as compatible research constructs; both are important to this issue. Sociomaterialism is a paradigm shift away from viewing humans as autonomous agents who dominate material resources to achieve an outcome, and interaction can be present in or part of intra-action. In this issue, Guerrettaz (2021) discusses intra-action versus interaction in depth.

‘Intra-action’ represents a reconceptualization of language pedagogy as entangled exchanges and transformations among human and nonhuman actors. For instance, a sociomaterialist perspective does not simply see pair work as two learners linguistically interacting and engaging with a book in ways that can be separated into bounded a priori units (e.g., learners, text, language). Rather, sociomaterialism views this pair work in terms of unpredictable, entangled, and polysemiotic intra-actions. These may involve a learner’s glances, ears, mouth, memory, and feelings; a page in a book; an image or text with sociohistorical connotations; a breath; and vocal chord vibrations. ‘Intra-action’ describes how humans and nonhumans can change together with- out a reliance on causality or preassigned categories (Barad, 2007).

This takes us to the fifth concept guiding our sociomaterial approach, ‘distributed agency.’ While relatively novel to language education research (Bagga–Gupta, 2015; Deters et al., 2015; Miller, 2012), the notion of ‘distributed agency’ quite helpfully explains how LLT materials work in language classrooms. “It is easy to think that ‘an agent’ should coincide exactly with an individual” (Enfield, 2017, p. 9). However, this common misconception fails to account for the ways in which “elements of agency” are often “divided up and shared out” among multiple entities and actors—across space, environment(s), objects, and people—“in relation to a single course of action” (Enfield, 2017, p. 9). Consider the fol- lowing examples: a member of a dinner party passing the salt to another, a journalist reporting on national television the controversial words of a politician, or a young man burning his draft card in public protest (Enfield & Kockelman, 2017). None of these actions could be accomplished without distributed agency among the various individuals involved in each event nor without key material entities, like the saltshaker, television, or draft card.

Materials wield power in educational contexts, by shaping action, conveying knowledge, and collaborating with other human and nonhuman entities. At other times, a material object can frustrate or confound its users (Fenwick, 2015; Miller, 2012). The material world is not inherently separate from human consciousness and agency (Fenwick, 2015; also Deters et al., 2015). Instead power and agency are “displaced and distributed” (McGregor, 2014, p. 212). Materials can “act, together with other types of things and forces to exclude, invite, and regulate forms of participation” (Fenwick, 2015, p. 3). This sociomaterialist perspective—that materials exert influence or force in emergent intra-action (Fen- wick, 2015; see also Barad, 2007)—flattens the prevailing human–nonhuman hierarchies in social science—which typically privileges the former.

Intention is a critical and complex dimension of distributed agency (Schweikard, 2017) that involves the overarching goals or purposes of one or more individuals involved in an action, activity, or event. Such intention(s) may be aided, impeded, or generally complicated by nonhuman forces. Moreover, the intentions that an action is predicated on do not always align with its end outcomes (Sloan, 2010). For example, a foreign language teacher may put into motion pair work materials and accompanying activity with the goal of affording students opportunities to interact in the target language. However, the outcome may involve unexpected patterns of interaction, like the French students in Guerrettaz (2021) who barely used the target language during a teacher-created jigsaw activity. Still at other times, preaction intentions and post-action outcomes align more closely. For instance, in Hasegawa (2021), a different example of a pair-work activity, which was semiscripted in nature, resulted in students using the target language—Japanese in this case—mostly as the teacher-created materials had prescribed. Thus, distributed agency also highlights how ‘purpose’—meaning initial intentions and final outcomes (Sloan, 2010)— is realized in entangled and emergent ways among the multiple sociomaterial forces that are implicated in an action, activity, or event.

In general, sociomaterialism also resonates with ontologies that emphasize relational and localized approaches to understanding the so- cial and material world (Rosiek, Snyder, & Pratt, 2019; Todd, 2016). Moreover, sociomaterialism expands the scope of the field of language education, veering away from the proclivity toward “linguistic exceptionalism” (Canagarajah, 2018a, p. 101): It destabilizes the tendency to priori- tize structural language and illuminates the significance of the myriad polysemiotic resources in the sociomaterial world. Thus, we deploy socio- materialism as an overarching theoretical orientation in our effort to define ‘LLT materials’ and ‘materials use’ through metasynthesis of the empirical research in this issue, as described in the next section.

METASYNTHESIS: EMPIRICALLY DEFINING ‘MATERIALS’ AND ‘MATERIALS USE’

For this introductory article, we undertook a metasynthesis of the seven empirical articles of this guest edited issue. This offered new overarching analysis of the qualitative empirical articles to answer two particular questions: (a) What are ‘LLT materials’ in these studies? and (b) What does ‘materials use’ mean in these studies? Meta- synthesis refers to a systematic, secondary, and interpretive analysis of a collection of qualitative studies on a similar topic (Lachal et al., 2017; Noblit & Hare, 1988; Timulak, 2014). Metasynthesis “stems from a need to review a particular field” of inquiry to provide an integrative analysis or an answer to a particular question that goes “beyond a single study” (Timulak, 2014, p. 8).

Snowball sampling was used to select the classroom-based studies of this issue and metasynthesis. We independently analyzed the overarching findings and theoretical orientations from the seven contributor articles, focusing on what constituted ‘LLT materials’ and ‘materials use.’ Analytic categories emerged around the types of onto- logical entities that constituted materials and the phenomena that enabled their existences. Then, turning our attention to materials use, our meta- synthesis incorporated salient concepts from previous definitions (e.g., Grandon, 2018, as cited in Guerrettaz et al., 2018; Matsumoto, 2019), to ex- amine ‘action’ and ‘interaction’ with materials in the contributor articles. These categories evolved throughout analysis.

The metasynthesis of the contributors’ findings and frameworks also led us to the overarching lens of sociomaterialism. In this issue, technology studies (Matsumoto, 2021; Thorne, Hellermann, & Jakonen, 2021), multimodal conversation analysis (Hasegawa, 2021; Matsumoto, 2021), ethnomethodological conversation analysis (Sert & Amri, 2021; Thorne et al., 2021), pedagogical ergonomics (Guerrettaz, 2021), practitioner in- quiry and new materialism (Kim & Canagarajah, 2021), and Indigenous paradigms of relationality (Engman & Hermes, 2021) arguably all fall under the purview of sociomaterialism (Fenwick et al., 2011).

LLT materials and materials use are ubiquitous elements of LLT settings worldwide yet they lack empirically based definitions to push scholarship forward. We note that other major areas within language education have historically benefitted from similar advances around definitions of important and complex constructs such as ‘language,’ ‘identity,’ and ‘language teaching methods,’ among others. Our metasynthesis, therefore, aims to propose much needed definitions to benefit LLT materials research and the broader field of language education. Our definitions of ‘LLT materials’ and ‘materials use’ begin with a critical observation about the conceptual relationship be- tween these constructs. While in a sense distinct, in many respects ‘materials’ and ‘materials use’ are sibling concepts best understood in terms of one another.

Sibling Constructs

MUSE International scholars have frequently noted the difficulty of accurately and comprehensively defining ‘LLT materials’ and ‘materials use’ (MUSE International, 2019). One possible reason for this is that what constitutes an LLT material varies from one context to another, as exemplified in this issue: Materials adapted to standardized tests are common in ELT (Kim & Canagarajah, 2021) seeing that this is a dominant international language, while natural surroundings like forest wildlife are often deployed as material resources in Indigenous language learning (Engman & Hermes, 2021). Both examples are rooted in the unique historical, social, cultural, and political contexts of the language in question. Context arguably determines what types of entities can act as LLT materials, how learners receive them, how appropriate a given material is in that setting, and many other considerations regarding their use. Hence, no one study in a single context can adequately or comprehensively define ‘LLT materials,’ especially at this early stage of materials use inquiry. Herein lies a benefit of this metalevel, synthesizing analysis.

A second and related reason that materials are difficult to define is because their meanings and roles are changeable, emerging in intra-action. For instance, a textbook itself—leaves of paper imprinted with text—is likely not particularly remarkable to a language teacher as an object unto itself. Rather, it is in the learners’ intra-actions (e.g., with the book and one another) that the salient features of the book-as-materials become apparent.

The significance of ‘use’ to these sibling constructs—LLT materials and materials use—is especially evident in examples of less prototypical materials in this issue, such as a tree branch for teaching Ojibwe (Engman & Hermes, 2021), campus structures like a fountain encountered in an augmented reality (AR) language learning game (Thorne et al., 2021), and a spontaneously played Bob Marley song on a student’s cell phone (Matsumoto, 2021). Examples from this issue similarly illustrate what might be understood as the dynamic multifaceted ‘identity’ of a given LLT material. In Kim & Canagarajah (2021), a ‘lifestyle’ story in The Korean Herald about pop star Yoo Ah-in is a digital artifact of popular culture that takes on the dual ‘identity’ of an LLT material in the context of this English pedagogy.

The qualification of something as an LLT material depends on whether it is used as such, regardless of whether it was designed for language learning. This observation diverges from Mishan & Timmis’s (2015) aforementioned definition of LLT materials as things designed for a pedagogical purpose. Based on our metasynthesis, the designed purpose cannot be the universally defining characteristic of an LLT material. ‘LLT materials’ and ‘materials use’ are sibling concepts that are almost inextricably interrelated, so our definition of materials is anchored in use. In the next sec- tion, we unpack our complete definition of LLT materials.

Language Learning and Teaching Materials: An Empirically Based Definition

At the heart of our definition, an LLT material is an assemblage, or more specifically, an entangled and emergent assemblage of different ontological entities. Assemblages are multifaceted and characterized by their emergent, entangled nature. One compelling example of such an assemblage from this issue are the Ojibwe LLT materials in Engman & Hermes (2021). During a lesson designed around a nature walk, a young learner picks up a fallen tree branch to show his peer and their teacher—a Tribal Elder. The assemblage of the branch is comprised of organic matter from the tree, including the bark, pine needles, and other matter (e.g., inner bark, sap- wood, cambium). Ontologically, the assemblage expands as this branch becomes an LLT material, and the learners and Elder physically and linguistically interact in Ojibwe and with other elements of the natural world around it. Better put, as the researchers explain from an Indigenous worldview, the youth and Elder ‘intra-act’ with this piece of the natural environment. The fact that the branch is part of the forest environment on the reservation lands of the Lac Courte Oreilles Tribe is also an important sociocultural, spiritual, and political dimension of the assemblage. Other examples from the issue help to more fully ex- plain the notion of material-as-assemblage.

Moreover, across all seven studies, LLT materials are entities within the ‘perceptual field’ of the learner and/or teacher. This means that these entities can be observed, even if they do not take up space. For instance, materials are not limited to discrete physical objects; they can include things like a recording, which is auditorily though not typically visually or tactilely perceivable. LLT materials connect, engage with, or relate to the user’s sensory, affective, and intellectual perception.

Along with our understanding of materials as emergent assemblages, our metasynthesis also analyzed ‘the what’ of materials—meaning, what physical, virtual, linguistic, and other types of ‘things’ act as LLT materials.

Thus, we define LLT materials as follows: (a) physical entities, (b) texts, (c) environments, (d) signs, and (e) technologies within the perceptual field of the learner(s) or teacher(s); these are used with the ultimate intention of facilitating LLT and in some sort of principled way.

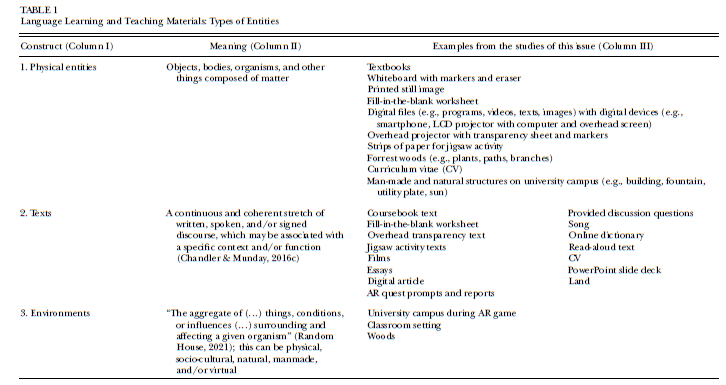

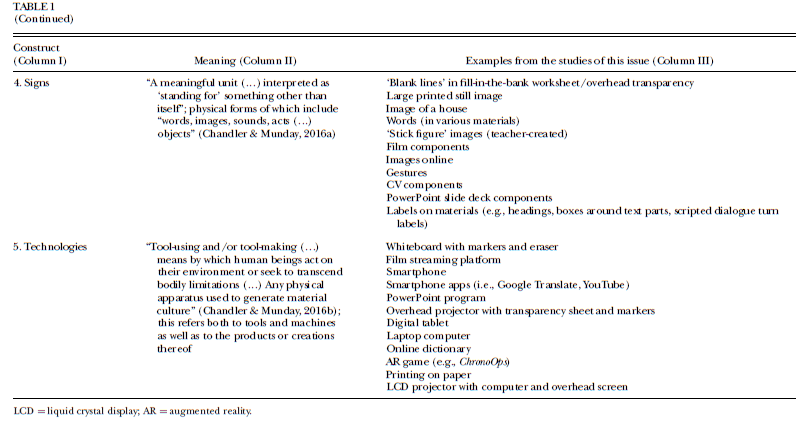

Table 1 offers explanations of each of these five categories, drawing on this issue’s empirical articles. The latter part of this definition clarifies that these cannot be any given thing used for any sort of action, activity, or event. The ‘principled way’ that LLT materials are used may be according to an official or enacted curriculum and/or other tacit or explicit principles like a textbook’s scope and sequence of topics or a teacher’s pedagogical values and knowledge.

Based on our metasynthesis of the seven articles, the five categories in Column I of Table 1 are comprehensive regarding the types of entities that served as LLT materials. Additionally, as Column III shows, most of these examples of LLT materials (e.g., a fill-in-the-blank worksheet, a list of discussion questions, an AR language learning game) do not neatly fit into just one category (Column I) but rather involve two or more. Thus, each LLT material (Column III)— meaning, each assemblage—“is more than one and less than many, not a multiplicity of bits nor a plurality,” borrowing from Fenwick et al. (2015, p. 98, citing Law, 1999). For instance, a textbook is both a text and a physical entity. An AR game is both a virtual environment and a technology (Thorne et al., 2021). Gestures, such as an Ojibwe Elder moving his hands away from one another, mimicking the tension of pine needles sticking firmly to their branch (Engman & Hermes, 2021), are signs representing something in the physical world. Yet they are also enacted by physical entities (i.e., bodies).

Essentially, a given LLT material is an assemblage comprised of different ontological entities or dimensions. Ontological differences (see Table 1, Column II) distinguish the five analytic categories (Column I) describing materials. For in- stance, the construct of a ‘physical entity’ (Table 1, Column I, Row 1) is categorically and ontologically different than a ‘text’ (Column I, Row 2). Regarding the former, physical material such as the paper and card stock constituting a textbook are composed of matter and typically perceived through touch. In contrast, text is not usually defined by its physicality but is instead more abstract and semiotic in nature. Text can manifest through sound, virtual means, or physically on a surface.

Real-world manifestations of some of these different ontological categories also overlap (see Table 1). For instance, signs (Row 4) can comprise texts (Row 2) (e.g., as letters in script make up the language in a book). From this issue, an LLT material in Kim & Canagarajah (2021)—the popular film Love Actually (Curtis, 2003)—is a case in point. This audiovisual text comprises countless signs, including a heart pendant around a lover’s neck, a picture of former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher at 10 Downing Street, and rough communicative gestures between new friends who lack a common language.

This category of ‘sign’ is perhaps the most abstract and expansive in Table 1 (Row 4). Scollon & Scollon (2003) explain signs as icons, symbols, and/or indexes, all of which appear in this issue’s empirical articles. First, icons resemble the very ‘thing’ they represent: for instance, a picture in a teacher-created material depicting a vocabulary word (Guerrettaz, 2021). Second, symbols arbitrarily link to their referent (i.e., what they represent) and require insider cultural knowledge to interpret: Examples include letters in script and certain culturally specific gestures. Third, signs can also be indexes whose meaning is determined by their specific placement in the world (e.g., a ‘blank’ in a fill-in-the-blank transparency; Hasegawa, 2021).

This typology (Table 1) brings the type of analytic specificity and coherence to the definition of LLT materials that has been lacking, but only addresses some aspects of LLT materials—namely, the types of entities that can serve as such, per our metasynthesis. This typology does not reflect the social and cultural content, broader power dynamics, epistemological grounding, or voices of the LLT materials in question, which are undoubtedly critical. For instance, the standardized test-driven materials observed by the practitioner–researcher in Kim & Canagarajah (2021) starkly contrast the student-created materials, which afforded learners an opportunity to push back against the hegemony of the standard- ized test. A striking example regarding the significance of cultural context is Engman & Hermes’s (2021) study of living forestland as interlocuting ‘materials-in-use’ in Ojibwe language pedagogy. Dynamics such as these are rooted in the intra-actions at hand, the local context, and the individual people and materials involved, which cannot be distilled into the type of simplified representations outlined in Table 1. This is a richness of the guest edited issue, where full articles unpack such dimensions of the LLT materials in question.

Materials Use in Language Learning and Teaching: An Empirically Based Definition

Expanding on this empirically based definition of LLT materials, in response to our second question, metasynthesis of the issue’s seven contributor articles in combination with sociomaterialist concepts enable us to also define ‘materials use.’ Oxford University Press (2020) defines ‘use’ as (a) “the action of (…) tak[ing], hold[ing], or deploy[ing] (…) something” or (b) “the state of being used for a purpose.” This suggests that two foundational elements, ‘action’ and ‘purpose,’ are at the center of the construct of ‘materials use.’

Action and purpose are both relevant to long- standing questions of existence, agency, and human volition dating at least as far back as Aris- totle’s septum cirumstantiae ‘seven circumstances’ in Euro-Western academia (Sloan, 2010). These are better known in English as the wh-questions (i.e., ‘who,’ ‘what,’ ‘when,’ ‘where,’ ‘why,’ and ‘how’) and include the less commonly cited yet equally important seventh circumstance—‘by what means.’ Such ‘means’ often refer to the physical components or ‘tools’ that facilitate action (Sloan, 2010), further highlighting how crucial the material world is to understanding action. Moreover, the septum cirumstantiae are of particular interest in this article because they capture a central aspect of materials use: understanding more than just the ‘what’ of LLT materials—though this has tended to be the primary focus of most previous studies. Instead, research should also examine the ‘who,’ ‘when,’ ‘where,’ ‘why,’ and ‘how’ of LLT materials—which is to say, materials use.

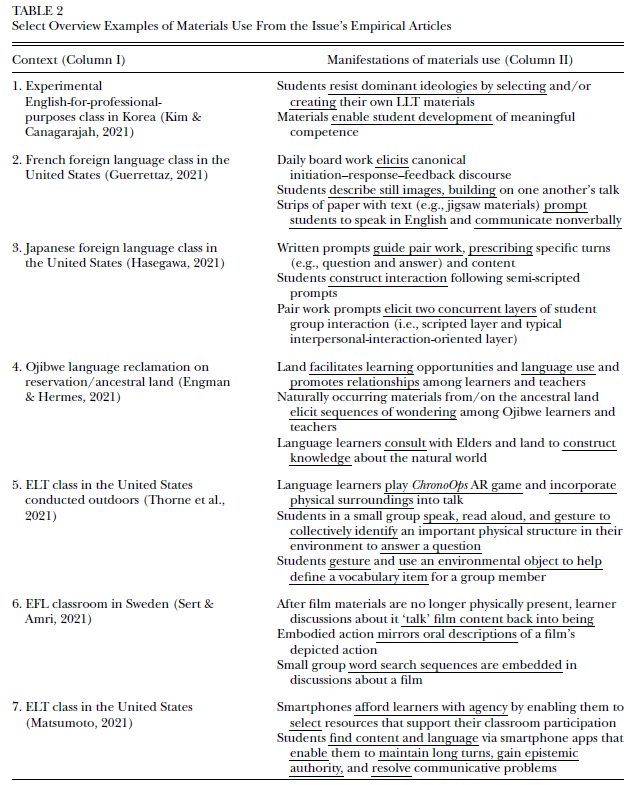

Thus, we attend to the overarching circumstances and put these guiding concepts—‘action’ and ‘purpose’—in dialogue with our metasynthesis of the issue’s empirical studies in order to preliminarily define materials use. Table 2 outlines examples across these diverse contexts of LLT. Actions are underlined, as this is one of the two core components of materials use (Table 2). The other—purpose—cannot be extracted or identified quite as succinctly, and is thus discussed here only briefly. The full-length articles provide more in-depth information about the purposes of the materials use in question.

Basic dictionary definitions (e.g., Oxford University Press, 2020) suggest that actions—like those in Table 2—characterize the construct ‘use.’ However, holistically, each example of materials use (Table 2, Column II) is more accurately an intra-action because each necessarily involves multiple forces, like a teacher, learners, and an LLT material acting upon and with one another. Not a single example of materials use involves an action occurring on its own in relation to one sole entity or agent. Dynamic ‘intra-actions’ (i.e., ex- changes, influences, or engagements) among materials, learners, and teacher constitute materials use (Guerrettaz, 2021). Such intra-action includes core classroom phenomena, such as interaction, pedagogical practice, classroom activity, and learning, among others that this issue explores.

Moreover, the various intra-acting forces (e.g., materials, learners, teacher) exert distributed agency during interaction, pedagogical activity, and more. From the perspective of syntax and semantics, many manifestations of materials use from the contributor articles illustrate inanimate materials influencing the human actors and processes of the language learning setting (Table 2, Column II). Yet sociomaterial perspectives go beyond syntactic agency to instead suggest that materials are part of a network of forces that act together in a classroom.

For instance, one of this issue’s articles focusing on digital technologies, Matsumoto (2021) illustrates how a student’s epistemic authority drastically shifted through use of a mobile device (Table 2, Row 7). Thus, agency was distributed among learners and the digital mate- rials. Hasegawa (2021) analyzes student use of semiscripted pair-work prompts, which involved discourse routines that students seemed to learn over the course of the term (Row 3). Thus, the “power and agency of teacher or task designer are displaced and distributed” across time and space, most notably through the material prompts (p. 81). Additionally, Thorne et al. (2021) describe a student group’s outdoor audio-video report about the typically rainy weather in their locale (Portland, Oregon). Ironically, bright sun- light momentarily blinds the narrating student, thus disrupting and prompting him to revise his presentation while joking about the unusually sunny weather. The sun as a nonhuman entity exerted material agency, affecting the student presentation (Row 5).

Distributed agency helps explain not only the complexity of such intra-actions among materials, students, and their broader circumstances but also students’ unpredictable responses and reactions to materials. Neither teachers nor learners have complete control over the outcomes of mate- rials in use. Even when there are clear human purposes at play, the outcomes of materials use intra-actions are emergent in nature. Hence, as with the definition of LLT materials themselves, materials use involves complex entanglements that make up a language classroom.

In light of the metasynthesis and the basic meaning of ‘use’ in relation to key sociomaterialist concepts, we propose the following definition. In language learning and teaching, materials use refers to entangled and emergent intra-action(s) among the teacher(s) and/or learner(s) and one or more LLT materials, which are precipitated by human participants but realized through distributed agency.

This definition alludes to an important tension that characterizes materials use: unpredictability and systematicity. As explained previously, sociomaterialism “views all things as formed through a dynamic conversation among order and disorder” (Fenwick et al., 2011, p. 19). This tension is manifest in the articles in this issue. For instance, Engman & Hermes’s (2021) study of multilingual Ojibwe learners walking through local woods with Elders shows how seemingly disordered ‘free’ exploration of space yields organized episodes of talk and interaction (Table 2, Row 4). Bodies move across the plane of the forest floor, alternately following and ignoring trails with no pre-established objective or leader to organize movement and interaction. Yet, the human and nonhuman elements gathered there self-organize to construct knowledge of language and land through emergent practices of observation, use of polysemiotic attention-getting frames, and intra-action with the naturally occurring materials. Similarly, complex sociomaterial patterns emerge in Kim & Canagarajah (2021): Student learning goals and activities shift and advance through use of learner- (i.e., self-) generated LLT materials, as they grapple with hegemonic ideologies (e.g., test-driven language learning, sexist work- place cultures) and direct their own language learning (Table 2, Row 1). Learner desires and motivations—which can be both unpredictable and systematic—are primary organizing forces in that study of materials use. Finally, the tension between systematicity and unpredictability is at the center of pedagogical ergonomics (Guerrettaz, 2021), which aims to identify and optimize sociomaterial ‘action patterns’ in classrooms (Row 2). Discovering previously unidentified patterns of sociomateriality in language classrooms, which are at the same time subject to unpredictability, is arguably one of the richest challenges of materials use inquiry moving forward.

The examples of materials use in Table 2 reveal that the numerous contributors to this issue interpret and investigate the concept of ‘materials use’ differently, engaging with varied subfields in language education and highlighting diverse sociomaterial concerns. For example, materials use involves interactional and discursive phenomena, questions of pedagogical approaches, the enacted curriculum, issues of power, and more. The complete analyses provided in each of the seven articles offer critical information about the construct of ‘materials use’ across diverse contexts that can- not be adequately explicated in this one synthesis article alone. For these reasons, our aforementioned definition of materials use is preliminary. Guerrettaz (2021) goes on later in this issue to focus squarely on the notion of ‘materials use,’ particularly from the perspective of materials in class- room interaction and activity, thereby honing the working definition presented here.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This introductory article draws on sociomaterialism and deploys metasynthesis to provide empirically based definitions of ‘LLT materials’ and ‘materials use’ that account for a broad range of materials in diverse contexts. Since our definitions are among the first empirically based ones, we also invite subsequent refinement and discussion of these. We have attempted to show here that ‘materials use’ is not a peripheral concept or an add-on to the existing field of materials development and evaluation. Scholarship on LLT materials has often unfortunately been perceived as “an essentially atheoretical activity, and thus unrewarding as an area of research” (Samuda, 2005, p. 232;7 see also Garton & Graves, 2014). Nonetheless, applied linguists (e.g., Canagarajah, 2018a, 2018b; Pennycook, 2018) have recently be- gun examining classrooms from innovative theo- retical perspectives that highlight the significance of the material world.

Insights from sociomaterialism help to clarify the unpredictable, dynamic, and situated intra-actions of language learning—concepts and matters of great importance not only for researchers of LLT materials and materials use but also for practitioners. Sociomaterialism rep- resents a move away from the decontextualized structuralism of one-size-fits-all epistemology that underlies many curricula and even the notion of ‘best practices’ in language teaching (see Toohey, 2019). By focusing on intra-actions among and within assemblages rather than on bodies, objects,and language as ‘separate’ entities, our general conception of language teaching and learning also shifts. It presents a view that “educational processes are more-than-human” (Fenwick, 2015, p. 7), involving social and material phenomena. Moreover, sociomaterialism offers a theoretical explanation for the ‘details’ of language teaching that dominant research paradigms often over- look. It thus affirms how these day-to-day realities of the classroom are quite important and in themselves extremely complex.

The elegance of this conceptual approach to materials use research, borrowing from Fenwick et al. (2011), is that “rather than simply assert- ing that classrooms (…) are complex or messy, sociomateriality provides us with ways of engaging that complexity in detail in order to better under- stand its implications for learning, education, and change” (p. 166). For many experienced practitioners, especially those in contexts not dominated by Western colonial paradigms, sociomaterial approaches are not necessarily a radical shift in thinking. The relational, the local, and the ‘now’ are where we are most able to understand what and how learners are making sense of in their social and material life-worlds.

Sociomaterialism validates the variable, creative, and oftentimes puzzling classroom dynamics with which many language educators are likely familiar (e.g., Levine, 2020). Arguably, sociomaterialism also invites teachers to approach their work with less attention to control and predictability, and greater attention to facilitating and responding to what emerges via the entanglements of their classrooms. Unexpected outcomes are not necessarily pedagogical failures but rather indicative of the complexity or unpredictability of a particular assemblage. Thus, teachers may benefit from training that emphasizes recognition and responsiveness over controlled planning, encouraging them to think as much about social and material enactments as they do about individual growth (Fenwick, 2015).

Research that relies on concepts from diverse sociomaterialist paradigms has the potential to generate scholarship with wide-ranging benefits for materials use and language education more broadly. Materials use in LLT represents not only a relatively novel construct, but also an important and vast new area of language education research. Together, this introductory article and the articles in this issue provide a much needed direction for such scholarship on LLT materials and materials use.

注:本文选自The Modern Language Journal 105(2021)3-20。由于篇幅所限,注释和参考文献已省略。