Ecological approaches to language learning and materials use represent educational settings as complex and dynamic systems by applying relational perspectives from the natural world in the classroom. For young bilingual Ojibwe learners, the natural world (i.e., local, rural, and reservation land) is a significant language learning resource unto itself. In the underrepresented context of Indigenous language reclamation in the Upper Midwest of the United States, local land is central to ways of knowing and being, thus it is also central to learning. This study examines the ‘intra-actions’ among land-based materials, an Ojibwe Elder, and immersion school youth on local forestland. Focusing on the interrelated nature of human and nonhuman elements, we rely on Indigenous perspectives of relationality and sociomateriality to expand and clarify the roles of land in Indigenous language learning for reclamation. This study highlights Ojibwe practices of relational consensual engagement with the environment and has implications for materials use research, as it underscores the significance of the natural world as emergent language learning and teaching materials.

Keywords: Indigenous language reclamation; sociomateriality; land-based pedagogy

IN THE FIELD OF LANGUAGE TEACHING and learning, the term ‘classroom materials’ has long functioned as shorthand for text-based instruction inside walled classrooms (Tarone, 2014). In recent years, research on materials use in language teaching and learning contexts has expanded in scope to address the wide variety of textual (e.g., books, maps, handouts), physical (e.g., realia, cuisenaire rods), and virtual (e.g., websites, podcasts, video and audio recordings) supports that teachers and learners draw on to promote learning and development. Nevertheless, this increasingly diverse body of scholarship has yet to address the role of the most significant language resource available—land.1 For many Indigenous peoples, land is not only the physical space where and with which humans and their languages have grown and changed, but it is also significant for keeping time, organizing knowledge, and structuring Indigenous lifeways (McKenzie, 2020)—relations that are typically kept apart from language in research on language learning and teaching materials (LLTMs) and materials use.

The field of Indigenous language reclamation, however, holds language and land together as part of a ‘decolonial intervention’ (Leonard, 2019) aiming to disrupt the social structures at the root of language shift. While reclamation ‘practices’ can resemble the efforts that are typically associated with language revitalization (e.g., documentation, policy making), the overall aim of remaking relations with and through language is a deliberate turn toward epistemologies and ontologies that delink (Mignolo, 2007) from colonial structural thinking. In the underrepresented context of Indigenous language reclamation in the Upper Midwest region of the United States, local land is central to ways of knowing and being; thus it is also central to learning. A land-centered paradigm offers significant insights into sociomaterial engagements among language learners and the natural world, particularly for Indigenous language teaching and learning contexts.

This deliberately interdisciplinary study (i.e., applied linguistics, Indigenous studies, linguistic anthropology) brings Indigenous perspectives of language and land into dialogue with LLTMs and materials use research in order to clarify and expand conceptions of materials as both emergent and dynamic. We look to local land as an alternative representation of ‘classroom materials’ and examine the relationships enacted and em- bodied among young bilingual Ojibwe learners, first-speaker Elders, and land in a naturally occurring ecology—the forest beyond the classroom walls. The land-based reclamation context for this study shifts us from institutionalized spaces to the woods, from instructor–student hierarchy to flattened peer–Elder–nature relations, and from fabricated instructional resources to nature and the environment. Though grounded in highly specific ‘localness,’ this research resonates across a wide range of sociomaterial language learning engagements as it reimagines learning in relation to place and space.

INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE LEARNING FOR RECLAMATION

Intergenerational Ojibwe learning and use builds on existing research with LLTMs by placing it in dialogue with scholarship on Indigenous language reclamation and land-based pedagogy. This is important because Indigenous scholars, educators, activists, and allies have long held that learning an Indigenous language for the purpose of revitalization or reclamation requires pedagogies and paradigms that differ from those typically employed in the well-represented con- texts of TESOL, bilingual education, or world language education (Hinton, 2011; Jourdain, 2013; White, 2006; Willow, 2010). This distinction is a direct outcome of an attempt to desettle colonial violence and theft, especially in terms of the academy (Pember, 2015; Smith, 2012; Spring, 2016) and points to the significance of self- determination (e.g., Marin & Bang, 2015; Tuck, 2009) and sovereignty (e.g., Engman & Stemper, 2017; Lyons, 2000) in the reclamation movement. In order to “validate the uniqueness of Native American culture within mainstream American or Canadian culture” (White, 2006, p. 104) scholar- ship must attend to the ‘uniqueness’ of language reclamation’s learning objectives—(re)learning one’s ancestral language for the purpose of restoring linguistic and cultural continuity ‘in place.’ It also involves conducting research that addresses the differences in Indigenous language- based motives, desired outcomes, distribution of resources, and materials (Hinton, 2011). In this section, we discuss research on language learning materials and language reclamation along with relevant work on land-based pedagogy and paradigms.

Materials for Indigenous Language Reclamation

In many reclamation contexts, state-of-the-art language-specific materials and curricula are rare, and existing materials can follow Western and colonial paradigms rather than Indigenous ways of knowing and using language. For in- stance, Meek & Messing’s (2007) examination of Kaska and Mexicano-Nahuatl language teaching materials found numerous examples of colonial language framing, which reinforced colonial dominance in Indigenous language spaces. This underresourcing requires Indigenous language teachers to rely on their own community knowledge, local resources, and bootstrap methods to engage students in meaningful language and culture development (Hinton, 2011).

Many of the Indigenous language teachers working in modern reclamation contexts are themselves learners of the language they are teaching. These ‘teacher–learners’ (Hinton, 2003) often have incredibly varied language abilities and pedagogical experiences. Importantly, these teachers are also in possession of expertise and creativity that current research paradigms centered on proficiency fail to track (Engman, 2017). For instance, Head Start teachers in British Columbia relying on the Stó:lo calendar as a literacy material for young learners (Moore & MacDonald, 2013), Ojibwe immersion teachers distributing tickets to students ‘caught’ speaking the language (Hermes, 2007), and Hawaiian immersion students working in taro patches (Luning & Yamauchi, 2010) demonstrate the range of materials and curriculum development that teacher–learners may include in pedagogies for reclamation. Yet, research on the specific ways in which these materials are deployed and taken up in context is limited, particularly in Indigenous language settings (for a few examples, see Galla, 2016; Meek & Messing, 2007; Moore & MacDonald, 2013).

This gap in our understanding not only points to a need for more usage-based research on materials in Indigenous reclamation settings, but it also highlights a paradigmatic shortcoming in the literature. Materials research that isolates the language from its situated use represents a ‘language-as-content’ paradigm. Such an approach to language teaching has been shown to be problematic, acting as a barrier for culturally relevant education (Hermes, 2005). Thus we are cautious in our call for more research on mate- rials use in reclamation contexts. The existing approaches, for the most part, tend to ignore the ways in which colonial education frames languages as an object (Richardson, 2011, p. 332) superseding Indigenous cultural knowledge production and creating curricular enclosures in which materials function. We worry that materials research might treat Indigenous languages as ‘contained’ content to be objectified and mastered. And so we are careful to call for materials research that stretches existing paradigms of language, of learning, and of the classroom.

Recent interdisciplinary work provides examples of alternative ways of understanding these phenomena. In a recent Perspectives column in The Modern Language Journal, numerous longtime Indigenous scholars and allies addressed these very concerns, exploring how ideologies of ‘language as a process of sustaining relationality’ (Henne– Ochoa et al., 2020) might look in different local community contexts around the world. The authors in this column centered their commentary around one particular form of learning that is quite common in Indigenous communities: learning by observing and pitching in (LOPI), which comes from Rogoff’s work with numerous colleagues in Central America (e.g., Alcalá et al., 2014; Paradise & Rogoff, 2009; Rogoff, 2014; Urrieta, 2015). LOPI sees learning as a process that happens in intergenerational, informal learning contexts. Instead of standardized learning objectives and patented instructional practices, LOPI emphasizes collaboration and context; and it offers an alternative to the decontextualizing functions of classroom-based language learning.

An Ecological Approach to Materials in Use

Guerrettaz & Johnston’s (2013) study of mate- rials use in one ESL class offers an example of how existing research frames might be stretched within a classroom. Their study of the use of a text in an English-as-a-second-language (ESL) class employed an ecological approach that centered systems of relationships in the ‘classroom ecology’ to better understand the role(s) that a given material can play in a given space. Though there are few points of resonance between a study of an ESL textbook and Ojibwe youth on a walk in the woods, one reported finding stands out: the occasional tendency among learners in Guerrettaz & Johnston’s study to perceive the text- book as a human participant. “The materials were sometimes portrayed as if they were, or represented, human participants with a will and a purpose” (Guerrettaz & Johnston, 2013, p. 785). Guerrettaz and Johnston theorized this behavior as representing how materials can serve as a proxy for their designers as well as for other physically absent parts of the classroom ecology. This raises new questions such as what or who ‘counts’ as a participant, and what elements of a given ecology are considered ‘present’ or ‘absent.’ By shifting the focus to relationships, an ecological approach attends to context and the dynamic interactions among different elements therein.

Importantly, ecological thinking has long been central to Indigenous language researchers as well (e.g., Meek, 2011; Nicholas, 2011; Simpson, 2014; Smith, 2012; Wilson & Kamana, 2001, 2009). The idea that Indigenous language initiatives are “never just [emphasis in original] about language” (May, 2006, p. 302) brings us back to the original, restorative purpose of language reclamation. Indigenous language teachers are not working to simply teach their youth and community members an additional ‘code’ (i.e., language-as-content paradigm). They are aiming for a restoration of fluency in a cultural medium that naturally supports and is supported by other cultural practices and ways of knowing in a complex, living ecology. In this way, language is seen as alive, just as the land—Mother Earth—is also alive. The land can be ‘read’ as a book may be read, but unlike a book, it is not a static object. Land is a dynamic, living text with its own history of resilience through settler colonial practices of occupation and extraction. Thus, the gap in the literature is more than a scholarly over- sight. Reclamation efforts aim to close a sociohistorical and sociocultural tear. Native people working for their language(s) are not only looking for the pieces of code, they are looking for the ways that it is used—how it is put together for different purposes (e.g., problem solving, relating, abstraction) in ‘place.’ Thus, a study of land-as-materials returns the ecological approach to its unique place in the systems of the natural world.

Land-Based Pedagogy and Paradigms

Though the biological metaphor for the class- room has proven useful for inquiry of materials use in the language classroom, this study is concerned with the nonmetaphorical significance of land in the construction of knowledge. Particularly in Indigenous education, the differences be- tween Indigenous ways of knowing (IWOK; Deloria, 1979; Kawagley, 1993) and ‘settled’ (Bang et al., 2014) understandings of the natural world are quite salient. This is evident in critical science and environmental education research that examines efforts at place-based education for Indigenous (and non-Indigenous) youth and families. For instance, in Bang et al.’s (2014) study of place-based education in the urban environment of Chicago, engagements with the land were crucial to the participants’ restorying of the environment and their relationships to it. Similarly, in a study of Native families on nature walks, Bang and Marin (2015) found that the use of Indigenous language in interaction with the land produced an “ontological transformation of the presumed possible relations between humans and non-humans” (p. 540). When families in their study interacted in English, humans were more likely to be represented in talk as distinct and separate from nonhumans. When the interactional medium involved Ojibwe language, the nonhumans in the natural environment were treated as agentic, and the resulting talk produced scientific knowledge about a wide array of environmental phenomena (e.g., erosion processes, life cycles, habitats).

Research that shows the knowledge-building across shifting ontologies highlights some important paradigmatic concerns for a study of land-as- materials in an Indigenous language reclamation context. One principal concern is that of the nature–culture boundary, whereby humans are seen as products of ‘culture’ and ‘history’ (In- gold, 2011), and therefore separate from nature (Bang et al., 2014; Bang, Medin, & Atran, 2007). This view is pervasive in Western and European perspectives, whereas Indigenous perspectives are more likely to integrate humans into the ecology. For instance, Bang et al.’s (2007) study of young children’s mental models of nature found significant differences between Menominee children’s reasonings of human–animal relationships and the reasonings of children of European descent. The researchers theorized this difference as coming from the Menominee children’s exposure to cultural teachings that support human–animal symmetry—teachings that were not present in the cultural repertoires of the European-descent children. The dissolution of the colonial nature– culture boundary is salient in this land-based Indigenous language context because the re- lationships that language mediates here are human–human as well as human–nonhuman.

Working from an Indigenous land-based paradigm requires a shift from thinking about categories and hierarchies to sense-making grounded in relationality. It requires a shift from thinking of humans as individuals above all other living beings, to thinking of recreating collaboration between beings. Rather than holding language proficiency as the sole objective, we aim for a goal of language in action that rebuilds relationships (among generations and the land). This orientation sees language use on land as pedagogical. Land is dynamic and complex, and in this context it becomes living learning materials. Simpson (2014) wrote about land as pedagogy, describing how learning occurs through engagements with land in a way that is both individual and distributed:

Within this system there is no standard curriculum because it is impossible to generate a curriculum for ‘that which is giving to us lovingly from the spirits’, and because it does not make sense for everyone to master the same body of factual information. (p. 10)

Our study takes this relational paradigm as a starting point for investigating Indigenous language learning ‘materials’ in an intergenerational, land-based context. We ask the following research question:

RQ. What kind of linguistic, environmental, and relational knowledge is structured through engagements with land as Ojibwe language learning materials?

THEORETICAL FRAMING

We frame this study’s deep interactional analysis with several theoretical perspectives from different fields, all of which can be thought of as part of a larger conversation converging around the nature–culture boundary. In our study, we intentionally blur the human–nonhuman binary by purposefully recreating and imagining what it is like for speakers walking in the woods from this framework. Connecting practice back to theory, we acknowledge the growing theoretical movement across disciplines that takes the nature–culture boundary as a central ontological force of colonization. This idea appears in work across a variety of disciplines concerned with decolonization as posthumanism or more than human (e.g., whiteness studies, Indigenous tradi- onal knowledge, feminism). The hierarchy that this nature–culture binary generates is recognized as deeply connected to the colonial project.

Feminist philosophers recognize the human–nonhuman divide as “the central dichotomy of colonial modernity” (Lugones, 2010, p. 743). For instance, European settlers’ perceptions of Indigenous people as ‘part of nature’—which contrasts with settlers’ perceptions of themselves as ‘outside of nature’—enabled the normalization of dehumanizing practices necessary for settling the land (Bang & Marin, 2015; Harris, 1995; Smith, 2012). For the field of applied linguistics, desettling the nature–culture boundary not only requires that we return language use to its natural environment, but also that we orient to language as a mediator of human–nonhuman relationships.

Indigenous Perspectives of Nature and Culture

Thus, in rejection of the nature–culture divide, we follow recent (Latour, 2013) and longstanding (Deloria, 1979; Kawagley, 1993) turns toward “intertwined reciprocal nature–culture relations” (Bang & Marin, 2015, p. 531). This orientation is recurrent in Indigenous philosophies, and yet it is lost in views of curriculum as something we ex- tract knowledge from, rather than create knowledge in relation to. Relationality is central. It resembles a network or web, holding humans and nonhumans alike. It contradicts a linear classification that places humans at the top of a hierarchy, above other animals and plants as if they exist solely as resources for our (human) benefit. In this flattened, web-like orientation, reciprocity is clearly implied among living things (and among some things that Western science classifies as non- living). Following Simpson (2014), the land in our study is not simply a static nonhuman, material entity; it is seen as a participant, a living teacher that takes many forms and structures countless re- lationships.

While the relationality principle in Indigenous epistemology contradicts the human–nonhuman divide of Western scientific thinking, we extend this concept to the relationship building that is necessary in the work of Indigenous language reclamation and education. Second-language learning within schools and the academy is concerned with language as a static object of study, a system of skills to be mastered. Too often divorced from context in language classrooms, learning a second language is traditionally expected to take the form of a carefully measured process of acquisition located in the individual (Long, 1990).

In contrast, the learning of Ojibwemowin and other North American Indigenous languages as additional, heritage, or ancestral languages tends to involve social investments in community (Hinton, 2011) and relational work that can be performed bilingually and that reestablishes connections between humans as well as between humans and land (Tuck, McKenzie, & McCoy, 2014). The goal of Indigenous language reclamation is to restore intergenerational relationships where the language was traditionally transmitted ‘in the wild’ (e.g., Fishman, 1991; Hinton & Hale, 2001; Leonard, 2011, 2019). In other words, although they are important sites of reclamation work, immersion schools and language classes are not the focus of the reclamation movement. Instead, the heart of the movement lies in restoring ways of being and relating to one another in the language. It is relationship building (through the language), which differs from many second-language learn- ing objectives. As Indigenous languages and cultures have evolved in particular places, in relation to the land and the many relatives there, the idea of language as making relations can be lost.

The concept of relationality is an epistemic principle that organizes many Indigenous peoples’ way of thinking and has been established in numerous scholarly works (e.g., Deloria, 1979; Kawagley, 1993; Kimmerer, 2013). We view it here as a way of generally organizing relationships between beings as a network, rather than a dichotomy or hierarchy. Relationality is part of an Indigenous epistemology that organizes land, language, culture, and all living things in relation to each other (Cajete, 2000; Medin & Bang, 2014; Smith, 2012; Tuck & McKenzie, 2015). This ontology stands in stark contrast to a dichotomy’s categorical divide between humans and nonhumans. In approaching this research, we focus on the relationality of humans to the natural world as a part of, and not apart from, the living semiotic resources in the forest.

Sociomateriality

Our reliance on Ojibwe orientations to land and language as dynamic and part of the web of human and nonhuman social relations resonates with sociomaterial perspectives of learning and knowing (Fenwick, 2015). These poststructural orientations expand the scope of the perceptual field (i.e., the range of salient phenomena in a given situation) while simultaneously flattening any hierarchies of participation that privilege “the intentional human subject” (Fenwick, 2015, p. 2). The benefits of taking a sociomaterial approach to language learning, particularly on land, is that it allows for the material world to intervene in the social world, to even take part in a given sociomaterial assemblage. Trees, animals, weather phenomena, the forest floor—all mate- rial entities—are dynamic features of land and have the potential to shape the social and material meaning making of an interaction in the woods.

Relations are critically important to sociomateriality, as our understanding of some ‘one’ or some ‘thing’ is a relative process of meaning making. For instance, a fallen tree can shift the direction of a footpath, it can trip and injure a body moving over it, and/or it can provide a place to rest (among countless other potential actions). The position of the tree relative to entities nearby, the composition of the tree, the nature of its materiality (hard vs. soft, wet vs. dry), the tree’s stage of growth prior to falling, and forest life supported by the fallen tree (or destroyed by it) all hint at the heterogeneous elements related to this fallen tree as a material. Any of these elements may or may not be enacted in a particular assemblage (Canagarajah, 2018). In other words, sociomateriality comes with relational assumptions that do not see materials as discrete and static ‘things.’ Rather, they are “gatherings of heterogeneous, natural, technical, and cognitive elements” (Fenwick, 2015, p. 5) that act together and upon one another in intra-actions (Barad, 2007). ‘Intra-actions’ refers to the ways that these heterogeneous elements ‘act together.’ This focus on intra-actions rather than interaction allows us to look for patterns within the unpredictable and distributed effects of human and more-than- human encounters.

This orientation to the social and material world is incredibly useful for understanding the use of language on and with land because it allows for patterns of language use to emerge from intra- actions among human and nonhuman elements alike. The overall ‘agenda’ of sociomateriality as a theoretical frame is still somewhat undetermined, but its inclusivity of nonhuman elements (Fen- wick, 2015) complements our primary framing of this study with Indigenous ontologies that allow for distributed agency across human and nonhuman subjectivities.

Co-operative Action and Substrate

Language is a cultural practice that mediates daily life and is in turn constructed by daily life (Butler, 2010). It is in these daily, unmarked, everyday ways of doing things in the social world that people embody, remake, and transform culture. For Goodwin (2018), the public social practices that comprise cooperative interaction are crucial to understanding culture “that human beings pervasively use to construct in concert with each other the actions that make possible and sustain their activities and communities” (p. 7). This is a decidedly different view from the ‘big C’ culture that is often represented in Indigenous reclamation work that links language to ceremony and traditional teachings. Yet this focus on the everyday is incredibly important to the overarching aims of language reclamation that seek to re-establish linguistic and cultural continuity. Though traditional knowledge and seasonal practices are integrated into some of the ideational content of the intra-actions represented in this study, they are not named as central to the practices of reading and relating with the land. Thus, all talk, gesture, gaze, embodi- ment, and silence are treated as performing intra-actional work collaboratively, and thus building culture.

Goodwin (2000) proposed an approach to human engagement that rejects a separation between language and the environment. The social and material environment shapes the kinds of semiotic resources available to the participants and can provide additional semiotic fields to hold attention and prompt further action. In this way, the environment can function as a ‘public substrate’ (Goodwin, 2013). Goodwin’s (2013) characterization of a substrate comes from a concept in biochemistry in which an enzyme transforms a molecule into another product. He saw this paralleled in interaction when a new action is built by operating and transforming parts of an existing complex of publicly configured semiotic re- sources. That is, substrates are the jumping off points for further communicative action, or in the case of this study, further sociomaterial intra-action.

‘Substrate’ played a fundamental role in both our transcription and analysis of the meaning making that occurred on and with the land. Ojibwe orientations to land tend to treat it as non-human but still very much alive and available for participation in meaning making. This means that while the environment can function in a way that Goodwin (2013) characterized as a semiotic field (contributing semiotic resources to the human participants like any materials in a given inter-actional context), its role in the interaction can also be more participatory. Importantly, although Goodwin (2000, 2013) provided examples of elements in the material environment (e.g., hop- scotch grid, Munsell chart) acting as substrates, he said that the co-operative ‘building’ action is something that people do. Goodwin (2018) argued that co-operative action has “the ability (…) to endow human history with its unique accumulative power, that is, as something progressively shaped by a consequential past while remaining both contingent and open-ended” (p. 3). We note that this accumulative power is, in fact, something that nature has had for eons—well before the arrival of humans. Thus, our decision to include the land as a contributor to the co-operative work of the assemblage is an expansion on Goodwin’s theory, bringing it into dialogue with sociomaterial orientations and Indigenous ways of knowing.

It is important to note that in this study, the land is not included as a contributor solely be- cause of its existence in the human actors’ perceptual field. Simply being there, adjacent to talk, does not warrant inclusion as an interlocutor in an analysis of meaning making. However, when land serves as a substrate for further social action or when its contributions intra-act with and build on the cooperative meaning making, our analysis makes space for it. We transcribed ‘intra- actional turns’ taken by the land following an expanded understanding of Goodwin’s (2013) substrate, and following the lead of the Ojibwe youth and Elder who engaged with land in this way.

METHODS

Our research builds on Bang & Marin’s (2015) investigations of the practices and pedagogical forms associated with desettling nature–culture relations. Their work identifies three cultural practices that Indigenous youth and caregivers use to construct meaning in ways that desettle nature–culture relations: (a) instructional launches, which are used to frame utterances that teach; (b) naming practices, which involve constructing creative relationships with nature through naming; and (c) reading land. It is this third practice that is the focus of the present study. Reading land “involves identifying and highlight- ing all kinds, entities and phenomena in the environment” (Bang & Marin, 2015, p. 536). This is important to the project of language reclamation, as reading land is a dynamic and intra-active practice, and it incorporates pedagogical forms that offer insight into the multiple literacies that multilingual Indigenous youth have access to.

Study Context and Participants

The forest walks that constituted the larger project that this research is based on took place on forestland in what is now northern Minnesota and northern Wisconsin in the United States. While these specific tracts of land may not be familiar to all of the participants, the landscape, the seasonal changes, and the plant and animal life contained there were not new to them. Elder and youth participants have spent most of their lives walking, playing, hunting, gathering, and living on that land. All walks were conducted in the spring (April or May) after the winter snow had melted completely.

The walk that is the focus of this article occurred near Hayward, Wisconsin and the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe Reservation.2 This land is especially familiar to the two youth participants because their Ojibwe immersion school Waadookodaading is located within walking distance of the woods. Both youth participants, Naawagiizhik and Manidood, are young male bilingual Ojibwe learners whose families are bilingual to varying degrees and committed to the project of language reclamation. Though they are not related to one another, they have grown up together in the close-knit community associated with Waadookodaading3 and are accustomed to doing things on their land in Ojibwe with one another. The Elder in the interaction, Joe, is an Anishinaabe4 man from the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe.5 He is a drum keeper and language activist who continues to work with the community and schools to grow and sustain language and culture.

Data Collection

Overall, we conducted 14 walks (each lasting 10–90 minutes) between April 2016 and May 2018 as part of a large Documenting Endangered Languages (DEL) project.6 Each walk consisted of at least one Elder and at least one highly proficient bilingual Ojibwe youth wearing microphones and point-of-view (POV) cameras to capture speech, gesture, embodiment, and gaze associated with both verbal and nonverbal attention frames. The recordings were then logged and transcribed. Ojibwe talk was translated into English by a bilingual Ojibwe language specialist who also checked transcriptions with Elders for accuracy. Videos associated with each participant were spliced to create layered multiview videos that allowed for the analysts to watch two and three perspectives at once. We viewed the videos multiple times from multiple perspectives and added embodied, nonverbal action (e.g., gestures, gaze, facial expressions) and environmental data to each master transcript. This aided in developing transcripts that attended to the ways in which gaze, gesture, embodiment, movement, and materials contributed to the action of collaborative meaning making (see Appendix for transcription conventions). We then watched the movies and annotated the transcripts again to divide the walk into ‘episodes,’ each of which consisted of spoken or embodied (or both) coordinated joint attention to practices involved in reading land (Bang & Marin, 2015). For the present study, we focus on one episode from a 20-minute walk conducted in May of 2018.

Data Analysis

Goodwin (2013) and Schegloff (2007) suggested that questions of human action (i.e., how a particular social action is accomplished) require a very close look at the work and resources involved in interactions. For Schegloff, these actions (e.g., requesting, inviting, granting, agreeing) organize sequences of turns, yet for Goodwin (2018), this approach “misses much of the work participants in conversation are doing” (p. 26). As our analysis seeks to highlight this ‘work’ that the participants are doing as part of the sequencing of actions that comprise reading land, we analyzed the episode for the communicative practices (both actions and attention frames) that structure co- operative interaction in the woods. Moreover, as we attended more closely to this ‘work’ of conversational interaction, particularly around reading land, we found that nonverbal and extralinguistic action were consistently entangled with the materiality of the environment. We found long stretches of silence that were integral parts of the interaction as human participants engaged directly with the land to perform actions similar to what might be done linguistically with other human participants (i.e., consult, speculate, co- construct an argument). This led to another iteration of transcription, one in which the land was afforded ‘conversational turns’ (via screenshots) alongside the human participants.

This second round of transcription required re- visiting the video recordings in order to include relevant screenshots of nonverbal interaction and to carefully document the ways in which the land was engaged as an active participant in the inter- actions. We relied on Goodwin’s (2013) characterization of substrate to clarify when the land could be seen as contributing cooperatively to the action, rather than simply hosting it as environmental context.

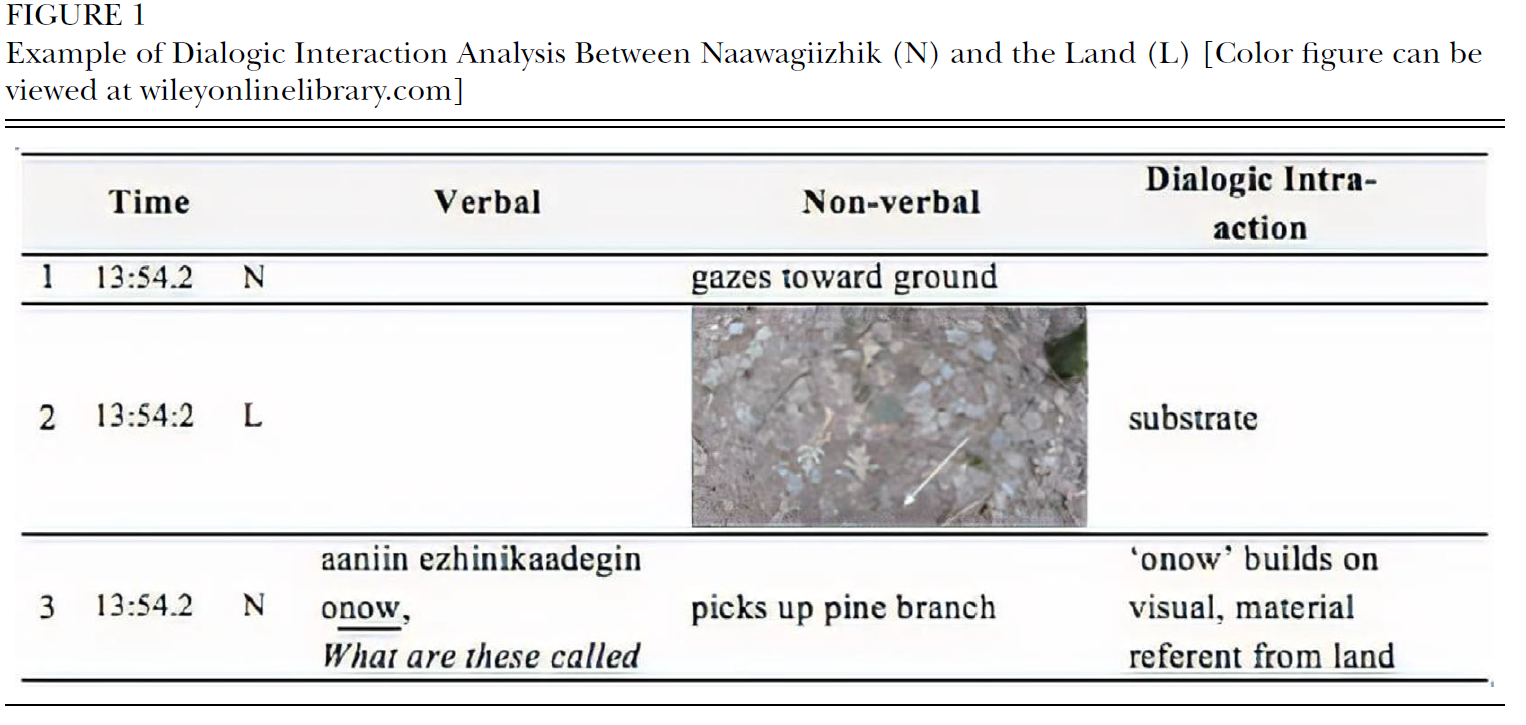

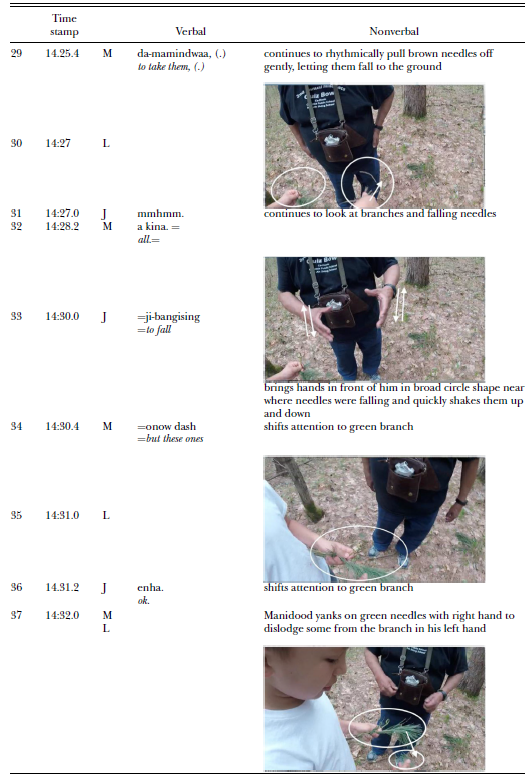

As all of the land’s contributions to the interaction were nonverbal, our use of substrate involved attending to how land was seen, addressed, touched, moved, shaken, and referred to in talk, gaze, and sensory engagements. The land was always present as environmental context, but it was only included in the transcript as an interlocutor (i.e., transcribed with a turn in the transcript, represented by a relevant screenshot from one of the participating human’s POV cameras) when it was seen to play a dialogic role in the episode’s action as either a substrate or an intra-active contributor building on an existing substrate. Figure 1 is an example of transcribed dialogic action between Naawagiizhik (N) and the land (L), accounting for the land’s contribution as an interactional substrate—something that “the participants use as the point of departure for transformative operations that create new action” (Goodwin, 2018, p. 32), or as a dialogic interlocutor that builds on previous action.

This mode of transcription aids our interpretation of the human and nonhuman elements in the assemblage as ‘entangled’ (Toohey, 2019) within a flattened and situated ontology of relations. Such an approach to the data views land as an intra-active contributor to making meaning, and is grounded in Ojibwe epistemological understandings of personhood in the natural world (Kawagley, 1993; Simpson, 2014). Additionally, sociomaterial orientations to learning (Fenwick, 2015) and Goodwin’s (2013, 2018) co-operative action anchored our analysis of the episodes of intergenerational participant frames relevant to ‘reading’ land intra-actively.

FINDINGS

Findings from this study highlight the role of land’s materiality in co-operative Ojibwe intra-action. Though evident throughout the several hours of intergenerational forest walks that com- prise the larger study’s corpus, here we present analysis of a single, minute-long episode of reading land (shown briefly in Figure 1). This episode highlights a recurring sequence of sociomaterial configurations of language use that emerge from intra-action with the land: (a) naming requests, (b) relational knowing, and (c) pitching in, co- operative action. These patterns illustrate the significance of land-based paradigms to the teach- ing, learning, and use of Indigenous language. They index participant structures that can inform Indigenous language pedagogies, and they show how the material environment of the forest and our Ojibwe participants’ orientation to it as a dynamic, living entity transform it from materials and context into an interlocutor.

Naming Requests

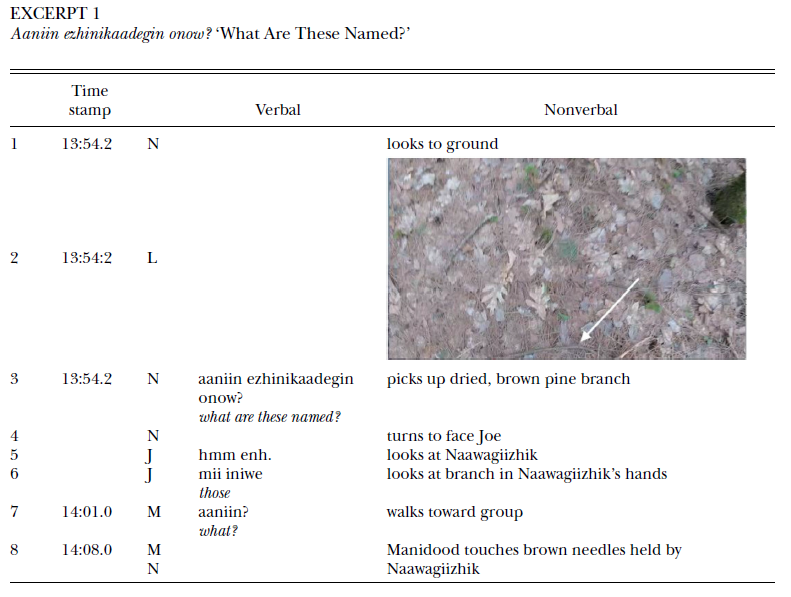

Many episodes in our corpus of forest walks begin with a youth or Elder looking at or pointing to something within the shared perceptual field and asking about its name. Sometimes the naming requests proposed a name in need of confirmation (e.g., Mii na waagaagin? ‘Is this a fiddlehead fern?’), and sometimes they were framed as direct questions with no prior knowl- edge (e.g., Awegonen onow? ‘Who are these?’). These language frames (i.e., mii na…? ‘this?’ and awegonen/awenen…? ‘what/who’) are learned early on and regularly employed to retrieve needed vocabulary in product-oriented language learning. Importantly, in the woods these naming questions function well beyond the lexical, informational requests that are typically found in language classrooms. Rather, across numerous episodes, naming requests served to gather attention, invite wondering, and initiate a sequence of sociomaterial intra-action. Such questions are process-focused. As Excerpt 1 shows, a naming request is not accompanied by a sense of urgency and entitlement to a specific label for a particular phenomenon. Instead, it is put forth with an anticipation of collective meaning making.

The episode begins with Naawagiizhik (N) gazing at the ground as he walks. The land shows a brown pine branch which serves as an initial substrate (i.e., the jumping off point for further intra-action), which Naawagiizhik builds on in line 3 by

asking a naming question of Joe, the Elder: Aaniin ezhinikaadegin onow? ‘What are these named?’ Joe (J) does not answer directly, but his speech in lines 5 and 6 serves to validate and encourage the wondering that was invited by the naming question. The other boy on the walk, Manidood (M), perceives their shared attention to something and joins the assemblage in line 7, taking hold of the branch in line 8.

The significance of naming in Indigenous languages has been established by recent literature that shows it to be a creative act that represents and builds relationships with the natural world (Bang & Marin, 2015). It has the potential to re- mediate nature–culture relations and it can bring this sociomaterial relationship to life in language. This is the case for Ojibwe and it stands in stark contrast with more colonial approaches to naming whereby the label ascribed to a place, object, or species tends to be bestowed by the person who encountered, created, or dominated it. Here the question Aaniin ezhinikaadegin onow? ‘What are these named?’ initiates a co-operative episode be- tween and among humans and land that indexes orientations to relationships across a variety of dimensions that include land and space, time, and materiality.

The role of land as a substrate and its co- occurrence with naming questions represents an important sociomaterial configuration for Indigenous language teaching and learning, where language is a point of access for many other social, spiritual, political domains, where the focus is on process rather than product. Denotationally, Naawagiizhik is asking a question about vocabulary. However, because he is able to ask this question ‘on the land’ and ‘in the language’ with a peer (Manidood) and an Elder (Joe), the question functions as something far more expansive than a request for a label. Joe’s validating yet non- committal response in lines 5 and 6 is one of many instances in our corpus wherein an Elder opts out of a direct answer. This is a skillful pedagogical move that is culturally sound in its redistribution of expertise across all elements of the assemblage, essentially inviting the person who posed the question to gather more information first (e.g., think on one’s own experiences, ask a peer, consult the land for clues). It is the move that extends this sequence into a collective effort to build academic language and critical thinking skills in Ojibwe.

Requests for objects’ and environmental features’ names on land are often followed by multiturn co-constructed wondering. Humans and nonhumans intra-act with one another to construct information about the phenomenon in question. This may have to do with the fact that some Ojibwe names refer to physical features of the thing they name. It may also be due to nature of the naming query overall. What is central to these open-ended sequences of wondering are the countless relationships that are entangled in ways of knowing a phenomenon that extend well beyond the boundaries of a label. For instance, without knowing the word for robin’s nest, one can still know where the interwoven twigs, earth, and other matter came from; who put them together; for what purpose; and when. Such knowledge may not reveal the Ojibwe word for robin’s nest, though it does reveal knowledge of complex entanglements among material relations over shared space and across time. This orientation toward knowing something as entangled in relations is central to Ojibwe language in use and to the sociomaterial configuration that tends to emerge after naming requests: relational knowing.

This configuration is uniquely anchored in land-based paradigms of teaching and learning, though the skills involved are easily transferable to academic environments. In order to know something relationally, learners need to hypothesize about processes, gather evidence with the environment, and make comparisons. Grounding this process of relational knowing in the materiality of the woods allows learners to gather information through touch, taste, sight, sound, smell, memory, and story. Inquiry can focus on the phenomenon in question as well as on adjacent and entangled phenomena, related either spatially or tempo- rally. For instance, inquiry centered on a (maybe) honeysuckle bush leads to taste testing and fore- casting a sweeter encounter in future weeks as the weather warms; a question about a nearby water feature leads to a story that begins with Chi- giiwenzh… ‘a long time ago.’ In Excerpt 2, we see the centrality of relational knowledge to wondering, and we see the importance of the forest’s materiality in co-constructing this knowledge.

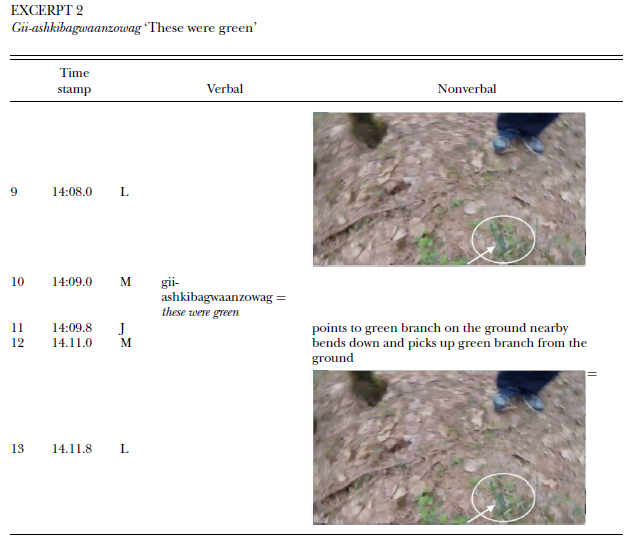

Having been invited to wonder together, Joe, the two youths, and the land collaborate to co- construct knowledge about the pine branch that was introduced at the start of the episode.

The land’s contribution (i.e., a pine branch in the boys’ hands) forms a new substrate in line 9. Manidood runs his fingers over the branch’s brown needles and asserts in line 10 that gii-ashkibagwaanzowag ‘these were green.’ In the absence of a name for this pine branch, this assertion stands in to represent another way of knowing—one grounded in experience. Manidood is able to draw on interactions with the land from prior seasons to contribute to the assemblage’s construction of understanding about its current state. He indexes an expanded timescale in talk, using the past tense marker gii- to describe how the branch must have looked at an earlier stage of existence, and this assertion is validated in subsequent turns where Joe points to a green branch on the ground nearby, which Manidood picks up and immediately runs his fingers through.

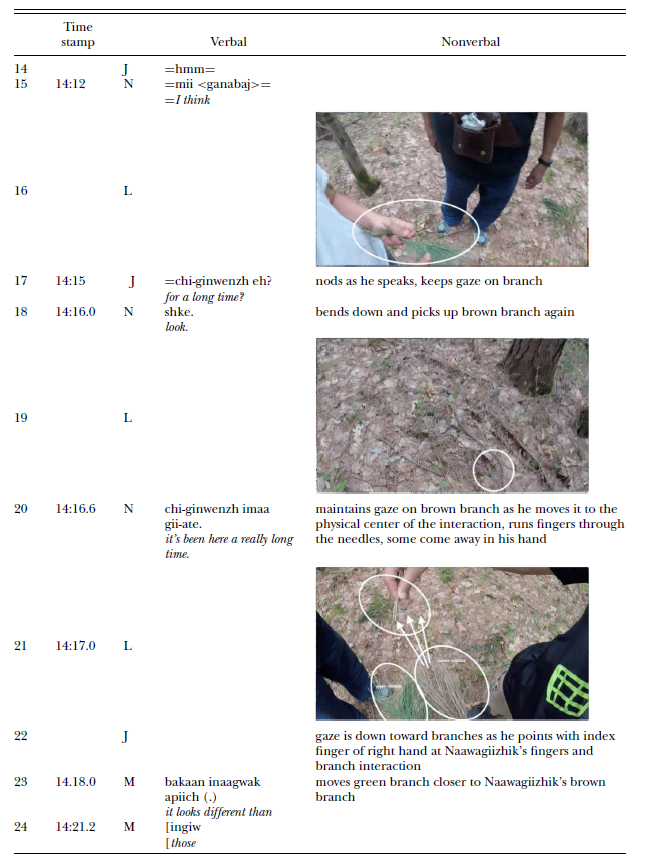

Elder Joe’s chi-giiwenzh, eh? ‘a long time ago, eh?’ in line 17 builds on Manidood’s earlier utterance gii-ashkibagwaanzowag ‘these were green.’ Naawagiizhik and the land then work together to build further on this by reintroducing the brown branch and regathering attention with shke ‘look’ in lines 18–19. Then in line 20, Naawagi- izhik revoices and expands on Joe’s chi-giiwenzh ‘a long time ago,’ which not only adds to the growing consensus but also builds further on the importance of expanded orientations to timescales when reading the land. The knowledge that the brown needles were green before they were brown is knowledge of the nameless pine branch in relation to form, time, and climate. It indexes the kind of relational knowledge that orients the youth toward thinking about the descriptive life cycle of the branch (something that may or may not be represented in Ojibwe naming) and it prompts further intra-actions among humans and land.

Naawagiizhik and the land continue to collaborate in line 21, showing how the brown needles fall away easily, as Manidood brings the green branch in closer proximity and gives voice to the physical reality of brown versus green needles in lines 23–24. The importance of physical experiences to the knowledge being constructed is evident in ways the humans touch the branches, their bodies intra-acting with land as fingers and gravity pull the dislodged needles toward the earth. Physical engagement with the land’s materiality is integral to reading the land and to constructing relational knowledge. Moreover, by affording intra-active turns to the land, we are better able to see how the touching mediates an exchange of information that constructs knowledge with the land.

Pitching in, Co-operative Action

The sequence of emergent sociomaterial action represented here is highly collaborative. Everyone and everything is a potential resource. Across the numerous episodes in our corpus, we see human and nonhuman elements intra-acting, co-operating, and/or ‘pitching in’ to build knowledge about the land and the language. Co-operative knowledge construction relies on language frames that hypothesize, hedge, and speculate such as Mii ganabaj ‘maybe’ or Ingikendaan…

‘I think’ as they invite further co-thinking. It also takes the form of recasts; completion of unfin- ished utterances; embodied mirroring of physical action; and collaborative intra-actions with land, experience, and story. The final turns in this sin- gle episode, shown in Excerpt 3, show how important Indigenous and sociomaterial orientations are to an analysis of land-based language use. By dissolving the nature–culture boundary and flattening the humancentric hierarchy, these perspectives transform language-in-interaction into sociomaterial intra-action.

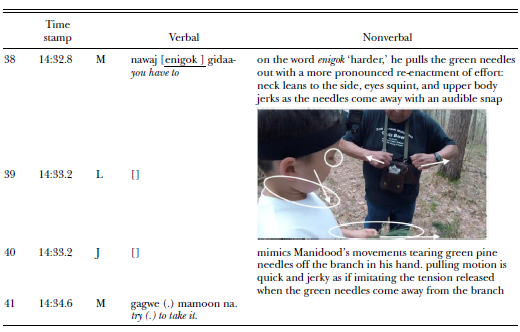

As the sociomaterial sequence of knowledge construction closes, there is a tremendous amount of co-operation among the human and nonhuman elements assembled. The pine branch with the brown needles holds the floor in the hands of Naawagiizhik. Manidood, holding the green branch, runs his fingers through the brown needles of Naawagiizhik’s branch as he describes the ease with which the needles come off the branch, beginning in line 26 (nawaj chi-wenipanad da-‘it’s easier to’) and ending with line 32 (akina ‘all’). As with other assertions in this sequence, it is grounded in his experience and familiarity with the land. However, there is significance here in the way that the human and nonhuman elements in the assemblage work together, pitching in to co-construct this embodied (27, 30, 33) and spoken (28, 31, 33) knowledge.

In line 26, Manidood tells how nawaj chi- wenipanad da-‘it’s easier to-.’ Then he pauses and the land continues the train of thought, showing how easily the needles do indeed come away from the branch (27). Joe pitches in as well in line 28 to complete Manidood’s utterance with da-mamindwaa ‘to take them,’ which Manidood echoes in lines 29. In the ensuing pause in talk, the land in line 30 and Joe in line 31 validate the assertion, which Manidood completes with akina ‘all.’ Finally, in line 33, Joe uses language and body to revoice the falling needles by saying ji-bangising ‘to fall’ while mirroring the falling action with his hands.

Manidood continues to use physical touch in his comparison of the green and brown pine branch, shifting his attention in line 34 to the green branch. He uses the contrastive dash ‘but’ and his body’s engagement with the green branch’s materiality to illustrate the distinction.

The land resists his attempts to dislodge the green needles from the branch and this cooperation culminates in a near simultaneous trio of concerted knowledge building in lines 38–41. In lines 38 and 41, Manidood says nawaj enigok gidaa-gagwe- mamoon na ‘you have to try and take it,’ and as he says the word enigok ‘harder,’ he stresses the word, squints his eyes, tenses his shoulders, cocks his head a bit to the side and pulls the green needles out as if with tremendous effort. The land be- comes audible in line 39 as the release of tension between the needles and branch creates a snap- ping sound. Furthermore, Joe in line 40 mirrors this sudden release of tension through gesture.

There is rich intra-action in this excerpt as land is recruited to hold the floor. It mirrors and revoices language just as embodiment mirrors and revoices land. This cooperation builds throughout the entire episode, and the last four lines, including Manidood’s embodied dramatization of the release of tension as the green needles come away from the branch, illustrate the overlapping and choreographed nature of talk, embodiment, gaze, and sociomaterial intra-action to co- construct knowledge on and with land.

The talk and embodiment of the falling needles in this excerpt are reminiscent of the informal learning practices of LOPI (Paradise & Rogoff, 2009). Practices associated with LOPI are not commonly found in the decontextualized, abstract, and primarily verbal teaching and learning that occurs within institutions. This is because LOPI is grounded in family and community activities. LOPI practices rely heavily on observation, concentration, and participation rather than centralizing language as the primary mediator to guide learning and demonstrate knowledge or skill. These kinds of activities are evident in the intergenerational Ojibwe interactions shown here and are especially salient during conversa- tional silences and during the land’s intra-active ‘turns at talk.’

DISCUSSION

This study returns the use of Ojibwe language to the natural social and material context that it grew from, and it reimagines land as materials that are alive, dynamic, and participatory in intra-actions. Working from a land-based paradigm, we show how knowledge is situated, embodied, and distributed across people and place, and how this is expressed in language in intra-action ‘in the wild.’

Land as Interlocutor

Language and land are connected and caught together in a way that stems from the entangled complexity of the world (Barad, 2007). That is, they are not simply two distinct strands that have become knotted (and can thus be unknotted). They are co-embedded; and the Indigenous and sociomaterial orientations employed by this study allow the nature of this embeddedness to manifest more clearly in intra-action.

While distributed knowledge is associated with Indigenous ways of knowing (and teaching and learning) it is also crucial to the endeavor of reestablishing a language corpus and shared understanding of language use in intra-action. The youth in this study are graduates of the local Ojibwe language immersion school—a tight-knit community of highly skilled language learners who are accustomed to working together to solve language puzzles. It is not uncommon for the learners at the school (including the teachers) to ask one another for help when a lexical, syntactic, or pragmatic issue arises. Individual mastery is not the end goal. Rather, community members of all ages work together with the aim of cultivating a robust language community that can reestablish the cultural and linguistic continuity that was disrupted by settler colonialism.

This phenomenon has special significance for thinking about the role of land as materials within Indigenous language reclamation. The land is not

only a participant because of shifting epistemological orientations to animacy and personhood that are evident in interactive frames. The land is a participant because its participation in the inter-actions around inquiry, wondering, and knowing is required. We are seeing an inversion of how ecological knowledge and language come to support one another. For untold generations, knowledge about the land (including plant life, animal life, climate, astronomy, etc.) was bound up and re- made in the language, passed from one speaker to another through conversations, stories, speeches, prayers, and practices. Now, because of settler colonialism’s disastrous intervention, young language activists find themselves looking to the land for clues about the language, rather than the other way around. Thus, particularly for language reclamation, the land is more than a learning environment and more than a text. The land is a living dialogic resource that can be consulted with all of a learner’s senses. The land is an interlocutor, capable of contributing to the co-construction of knowledge about phenomena that are, were, and will be.

Land and Language Teaching and Learning

The sequence of sociomaterial configurations presented here demonstrates the importance of youth-led learning to Indigenous language reclamation pedagogies. This episode is a telling case, but also one of many episodes that begin with a youth-initiated inquiry around naming and it generates rich and complex meaning making in the language. Central to each of these episodes is a naming request that organizes attention and invites wondering. As a participant frame, this naming inquiry has been discussed elsewhere such as in Bang & Marin’s (2015) study of Indigenous families exploring urban land. However, the naming requests in the present study are significant in their tendency to resemble Excerpt 1—meaning they were put forth by the youth participants rather than the Elders. This participant struc- ture follows oral tradition protocols, whereby the learner is the one who must initiate a request for broader and deeper understanding (Archibald, 2008).

The generative nature of these sequences high- lights Indigenous theories of learning that center on inquiry, experience, and story (Kimmerer, 2013; Simpson, 2014). The excerpts in this study show the potential for deep exploration and cultivation of critical thinking when the question or request for more information comes from the learner’s own curiosity. This is important to the field of Indigenous language reclamation because it not only models the experiential and relational aspects of Indigenous ways of knowing, but it also models a restoration of Indigenous ways of teaching. Note that this episode concluded without resolving the initial question of the name for the needles or pine branch. For teacher–learners with limited lexical knowledge, this is an incredibly important implication. An Indigenous way of teaching that encourages inquiry and exploration does not require mastery of labels or code. By taking a pedagogical approach that distributes knowledge across human and nonhuman resources, teacher–learners can make space for practices that build relationships in and with language.

CONCLUSION

The Indigenous epistemologies and ontologies that situate humans as part of nature do not apply only to Indigenous peoples. Relationality holds us all in entanglements with the natural, social, and material world. These entanglements are experienced (Cajete, 2000), felt (Million, 2009), and storied (Archibald, 2008) in ways that are not necessarily visible. Language use in context can help us map these relational entanglements, but only if we stretch our understanding of language beyond notions of a settled, discrete, oral code. Language is a multimodal range of sense making and relating that includes embodiment, gestures, senses, gaze, memory, and verbal production. Delinking from colonial conceptions of language (Makoni & Pennycook, 2005) changes how we might recognize ability and skill (Canagarajah, 2018) and thus reimagines how we might facilitate language development in multilingual learners.

The interdisciplinary perspectives that inform this research highlight the depth of relations that are sustained in Indigenous language use in and with nature, which also serve to remind us of colonial disruptions to these relations that persist in many forms. This study addresses concerns specific to the context of Indigenous language learning for reclamation in direct response to calls for scholarship offering alternatives to the colonial aspects of applied linguistics (e.g., Makoni & Pennycook, 2007; McIvor, 2020; White, 2006). As such, we do not claim it has implications for all language teaching contexts everywhere. The relational connection of language and place (Marker, 2018) for Ojibwe youth learners on tribal lands is differently configured for learners of English in a former British colony. This is not to say that colonial languages cannot contribute to a multilingual learner’s repertoire for sense making and relationship building. However, the explicitly decolonizing aim of ‘sustaining relationality’ (Henne–Ochoa et al., 2020) is not a primary language objective in many English and world language classrooms. This study contributes to the field of applied linguistics by illustrating how language, bodies, movement, materials, and land can build and hold relations with community in place—an alternative approach for thinking about language teaching and learning.

注:本文选自The Modern Language Journal 105(2021)86–105。由于篇幅所限,注释和参考文献已省略。