Materials use is a critical yet poorly understood dynamic of language classrooms. This study examines ‘materials-in-action,’ meaning how materials shape classroom interaction and activity, in a beginning-level French-as-a-foreign-language classroom. The conceptual framework, ‘pedagogical ergonomics,’ similarly centers on materials-in-action, and more specifically on ‘intra-action.’ This refers to actions, influences, engagements, and exchanges among (a) materials, and (b) the students and teacher. Polysemiotic analyses and action analyses of classroom activity were triangulated with interviews and focus groups. Findings first expound the pedagogical ergonomics framework as comprising intra-actions among human and material ‘actants’ that are co-substantiated with sociocultural and physical space. This involves the concept of ‘classroomscape.’ Then—drawing on pedagogical ergonomics—macro-level analyses of materials-in-action reveal 4 genres of materials use, each of which influenced classroom activity and interaction differently. Additionally, micro-level analysis reveals 3 polysemiotic patterns of materials-in- action: (a) cloze worksheet prompts that ‘mapped’ onto the students, (b) learners’ ‘snowball languaging’ in French—involving extended meaning-focused descriptions of images—and (c) a physically dynamic information gap where students unexpectedly avoided using French. Additionally, this article hones the definition of ‘materials use,’ substantively focusing on activity and interaction. Theory and practice con- verge in pedagogical ergonomics, with implications for both.

Keywords: materials use; interaction; intra-action; action; pedagogical ergonomics

MANY LANGUAGE TEACHERS OFTEN wonder what exactly to do with their pedagogical materials—such as handouts, the board, textbook, and more—to most appropriately and effectively promote language learning. This article addresses this consequential topic—namely, what ‘happens’ in classrooms with and around language learning and teaching (LLT) materials. Indeed, leading scholars have asserted that research into how LLT materials are used in classroom interaction is necessary to attain basic understanding of how language classrooms operate (Garton & Graves, 2014; Larsen–Freeman, 2014; Tarone, 2014). Moreover, the broader field has recently begun to acknowledge just how severely the physical dynamics of learning and teaching have been neglected (Canagarajah, 2018; Toohey, 2018). In response to such calls, this study of a U.S.-based French-as-a-foreign- language (FFL) class centers on materials use in LLT (henceforth ‘materials use’). This research clarifies what exactly ‘materials use’ means in the context of classroom interaction and activity (ex- panding on Guerrettaz, Engman, & Matsumoto, 2021, this issue).

Specifically, this qualitative classroom-based re- search into materials use examines ‘what hap- pens’ between (a) LLT materials (e.g., cloze worksheets, thematic images, jigsaw materials, the whiteboard), and (b) the students and teacher. In- deed, ‘materials use’ can be conceptualized, quite simply, as ‘materials-in-action.’ Some findings re- veal different overarching genres of LLT materials that affected how students generally engaged with each other, the teacher, and each material itself (e.g., physically and content-wise). Other findings detail common as well as effective examples of materials-in-use, unpacking how different materials shaped moment-to-moment discourse in both predictable and unpredictable ways, and discussing the learning opportunities that these patterns of materials use involved. In sum, the influences, engagements, and exchanges that occur among materials, students, and teacher in class- room activity and interaction are central to this study’s research questions (RQs).

These materials-use phenomena are analyzed through the lens of ‘pedagogical ergonomics,’ which aims to understand human–object engagements in classrooms. This novel conceptual framework (a) seamlessly links discursive and material dynamics of language classroom activity, (b) is concerned with both pedagogical theory and practice, and (c) focuses squarely on action involving materials. ‘Action’ is substantively and conceptually central to this research on materials use, which therefore deploys action analysis along with polysemiotic interaction analysis.

In sum, this article aims to triply advance the field, (a) through the substantive findings that clarify how materials shape a language class- room’s modus operandi, (b) by fleshing out pedagogical ergonomics as a new conceptual frame- work, and (c) by further honing the definition of ‘materials use’—building on the more theoretically oriented one presented in this special issue’s introduction (Guerrettaz et al., 2021, this issue).

MATERIALS USE AND CLASSROOM (INTER)ACTION

LLT materials are resources (e.g., entities, signs, texts, technologies, environments) used to promote language learning (Guerrettaz et al., 2021, this issue). The present study into FFL pedagogy helps address the dearth of classroom- based research on materials use, particularly for the teaching of non-English languages (Guerrettaz & Johnston, 2013; Matsumoto, 2019; cf. Hasegawa, 2018; Moutinho, 2017; Thoms, 2014). A leading scholar of materiality in general education, Sørensen (2009) asserted that qualitative research on materials use must begin by focusing on “something happening” (i.e., ‘what happens’ in the classroom among beings and things; p. 22). This resonates with recent definitions of LLT materi- als use: as ‘action’ involving materials—otherwise put, as materials-in-action (Grandon, 2018; Guerrettaz et al., 2021, this issue). Indeed, language pedagogy more broadly is about “doing” (Cow- ley, 2012, p. 21). “This ‘doing’ involves the (. . .) ongoing interaction of [learners’ and teachers’](. . .) whole physical bodies and the world we experience and act on” (Zheng, Newgarden, & Young, 2012, pp. 339–340). Notwithstanding, “remark- ably (. . .) few [studies] have considered how” second language (L2) students learn “by doing things with (. . .) texts and other [materials]” (Cowley, 2012, p. 21).

The few previous classroom-based studies of materials use—meaning, on materials in class- room interaction and activity—suggest a complex interrelationship between materials and interaction (Chun, 2016; Guerrettaz & Johnston, 2013; Jakonen, 2015; Matsumoto, 2019; Pourhaji, Alavi, & Karimpour, 2016; Thoms, 2014; Walsh, 2006). Particular kinds of materials unpredictably shape the quality and quantity of interaction from one classroom context to another (e.g., see Canagarajah, 1993 versus Pourhaji et al., 2016, on global English language textbooks). Yet some research shows that materials can also affect interaction in rather predictable ways. For instance, fill-in-the- blank materials in Guerrettaz & Johnston (2013) frequently induced ‘fill-in-the-blank discourse’— meaning, limited student language. Altogether, this literature indicates that materials influence interaction in both unpredictable and systematic ways.

Two oversights characterize most of this materials-use research. First, even in multimodality studies, it often underestimates the extent to which language inextricably intermeshes with the physical world (Canagarajah, 2018). To understand language learning, we must move away from linguistics-centric perspectives, instead examining action in “rich environments” (Cowley, 2012, p. 16). Thus, following Jakonen (2015), the present study reconceptualizes classroom interaction and activity as polysemiotic ‘action formation,’ meaning patterns of everyday activities composed of entangled “action streams” (e.g., linguistic action, communicative gestures, physical movement; Jakonen, 2015, p. 101). A basic example is a teacher orally explaining vocabulary while gesturing and writing on the board as different students nod, voice replies, and consult their textbooks. The central concept here, ‘action,’ (a) refers to the phenomenon of an agent “doing something [emphasis added]” (Stout, 2005, p. 3) and (b) “is inseparable from thinking,” learning, and teaching (Cowley, 2012, p. 16; see also Franks & Jewitt, 2001).

Additionally, action requires agency—the ability of an agent (i.e., an entity acting ‘on the world’) to bring about change or adapt for a particular purpose (Stout, 2005). This relates to the second oversight of previous studies on materials use: Most overlook ‘material agency’ and ‘distributed agency’ (cf. Matsumoto, 2019). Euro-Western social science traditionally sees agency as purely human and residing with the individual. However, scholars have begun recognizing ‘material agency’—that ‘objects’ influence humans, sometimes profoundly (Canagarajah, 2018). Similarly, ‘distributed agency’ acknowledges that the individual rarely ‘does’ anything alone but rather ‘co-acts’ with other beings and objects (Enfield, 2017).

To summarize this literature review, the field has neglected the material aspects of language teaching and learning (Canagarajah, 2018; Tarone, 2014; Toohey, 2018). Moreover, this study conceptualizes materials use quite simply as materials-in-action—otherwise put, as action involving classroom objects and the students and teacher. Such human–object engagements are also the focus of this article’s conceptual framework—pedagogical ergonomics.

ERGONOMICS AND INTRA-ACTION

Ergonomics is a vast multidisciplinary field that seeks to understand purposeful human activity, for example in the realms of industrial or office workplaces, medicine, energy systems, air trans- port, sports, and beyond (Pheasant, 2003; Wilson, 2000). Ergonomics is centrally concerned with patterns of human–object engagements, which are best understood holistically in relation to their sociocultural contexts (Wilson, 2000). Thus, ergonomics is arguably a sociomaterialist frame- work. ‘Sociomaterialism’ is an umbrella category of diverse theories and empirical approaches that examine connections between ‘the social’ and ‘the material’ (Fenwick, Edwards, & Sawchuk, 2011). Theory and practice inextricably inter- twine within ergonomics, which aims to under- stand sociomaterial activities and the “design” of these in “real settings” (Wilson, 2000, p. 559). Meaning, praxis is paramount in ergonomics. Since language pedagogy is also a purposeful human activity involving human–object engagements and praxis, a central goal of this article is expanding ergonomics to understand how students and teachers use LLT materials, hence the notion of ‘pedagogical ergonomics.’

Though coined by Okulova (2020), ‘pedagogical ergonomics’ has not been fleshed out theoretically or analytically. However, cognitive ergonomics—a related framework—has been deployed to research (a) types of mathematics textbooks that reduce math teachers’ cognitive load to improve teaching (e.g., supporting their thinking and actions), and (b) how materials design and use intersect in mathematics pedagogy (Choppin et al., 2018). Pedagogical ergonomics integrates the three branches of traditional ergonomics—cognitive, social, and physical—to eschew artificial boundaries between human thought, social activity, and the material world (following Wilson, 2000).

Traditionally, ergonomics’ core “unit of analysis” is “interaction” (Wilson, 2000, p. 652), referring to influences, engagements, and exchanges between humans and objects. For instance, ergonomics describes physical influences between a typist and computer mouse as interactions. Yet, in linguistics, ‘interaction’ is a central disciplinary concept referring to semiotic exchanges and meaning making among interlocutors. In this sense, a computer mouse and typist clearly do not ‘interact.’ Ergonomics problematically and confusingly uses ‘interaction’: Different terminology is needed to advance the pedagogical ergonomics framework.

The term ‘interaction’ in ergonomics basically explains how a ‘happening’ happens. Diverse sociomaterialist approaches also seek to make sense of ‘happenings,’ ‘doings,’ and ‘activity’ using concepts like ‘intra-action’ (Barad, 2007), ‘participation,’ ‘performance,’ and ‘enactment’ (Sørensen, 2009). Synthesizing such theories and conceptualizations of ‘happenings’ and ‘do- ings’ from diverse—and sometimes divergent— sociomaterialist paradigms (Fenwick et al., 2011; Leonardi, 2013; Sørensen, 2009; also Barad, 2007), pedagogical ergonomics, as proposed here, replaces the problematic ergonomics term ‘interaction’ with ‘intra-action.’ In pedagogical ergonomics, ‘intra-action’ refers to action involving emergent exchanges, influences, or engagements among interrelated entities or beings (e.g., teacher, students, classroom objects). Thus, similar to the other previously explained foci of this article, action is also central to intra-action (see Table 1).

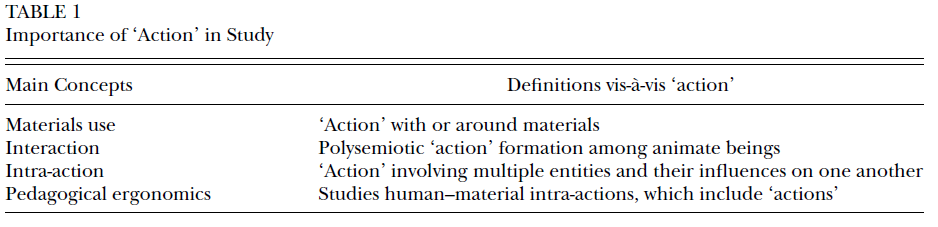

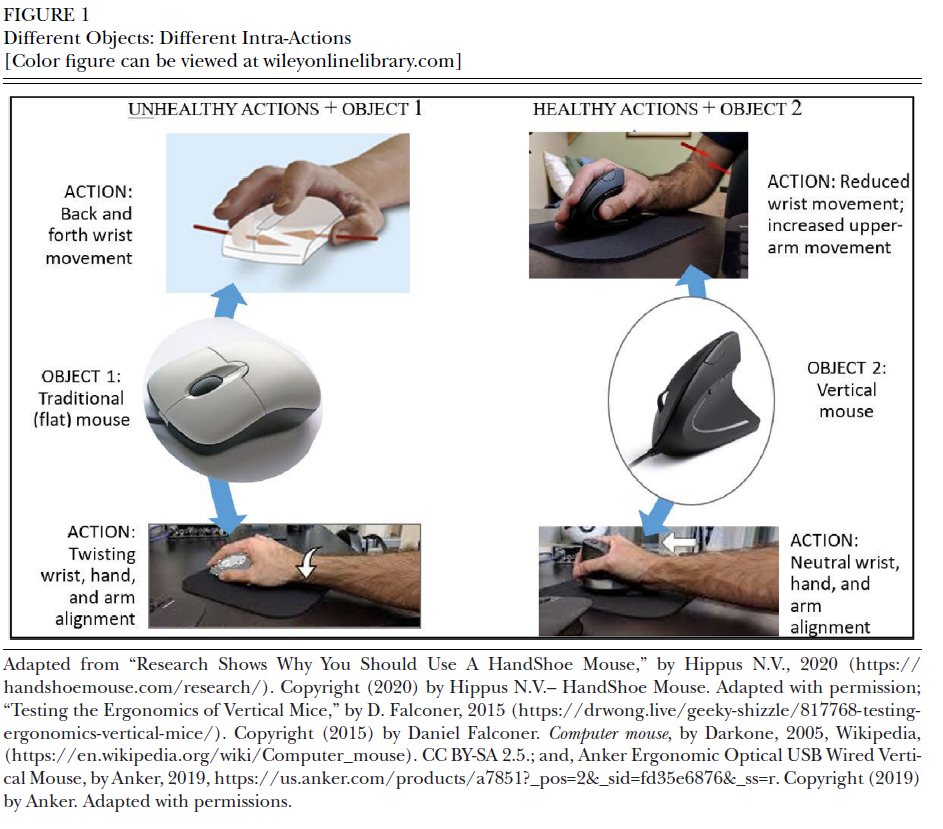

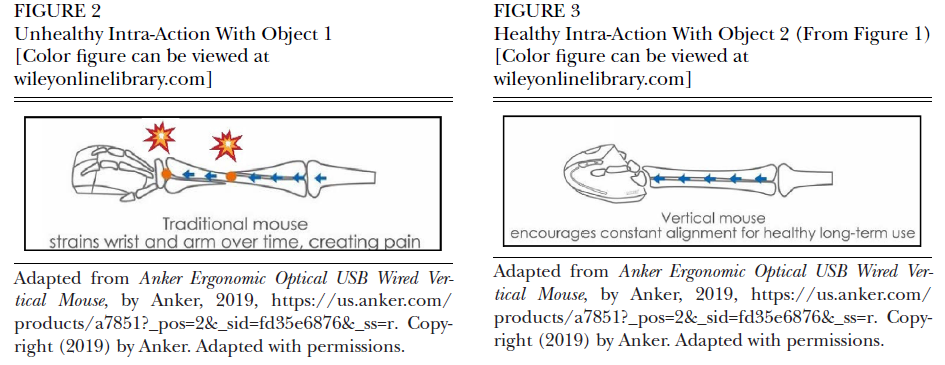

Action diagrams from workplace ergonomics (Figure 1) help visually explain intra-action as defined in the present study. The object and user intra-act to accomplish an activity. In doing so, just as a human user acts on the object (e.g., mouse), the object also influences the user. Specifically, a traditional mouse (shown in Figure 2) can injure the user long term (e.g., carpal tunnel), while the vertical mouse (shown in Figure 3) prevents in- jury. This simple example illustrates the significance of intra-action: Different objects can lead to different intra-actions; ergonomics aims to improve the outcomes of human intra-actions with objects (e.g., Figure 2 vs. 3).

Extrapolating this to the classroom, different LLT materials or actions by students and teachers can yield different intra-actions, which can involve better or worse outcomes vis-à-vis student learning. Figures 1–3 depict pseudomech-anistic intra-action between a human and objects. Contrastingly, classroom intra-action entails unpredictable activity orchestrated by a teacher authority—where ‘activity’ refers to individual or group actions to achieve particular aims (Lexico, n.d.-a; Sørensen, 2009).

In sum, the proposed pedagogical ergonomics framework seems well-suited for researching materials-in-action (i.e., materials use). More- over, intra-action is pedagogical ergonomics’ central concern. Findings will first expound these largely ‘untested’ ergonomics concepts—as applicable to pedagogy—into a full-blown pedagogical ergonomics framework. Then, the latter findings sections will deploy and build on that framework.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The overarching goal of this article is to under- stand how LLT materials shaped classroom activity and interaction. This was done by identifying patterns of materials-in-action, which were characterized by salient types and traits of the ‘component’ actions and materials. Both macro- and micro-level patterns were identified. Macro-level patterns of materials-in-action take a panoramic view of all the data to describe longer stretches of classroom activity in broader strokes, while micro-level patterns detail particular intra-actions in depth, similar in some ways to interaction analysis. With this overarching goal in mind, three RQs are addressed.

RQ1. What is pedagogical ergonomics, as related to LLT materials use?

RQ2. What were general types of ‘materials use’ in the FFL class under investigation, as revealed through macro-level analysis of classroom activity?

RQ3. What micro-level patterns of materials- in-action emerged in moment-to- moment interaction, and what language learning opportunities did these intra- actions involve?

METHODS

This qualitative exploratory research primarily involved classroom-based observation, analysis of classroom activity and interaction, and inter- view methods. Human subjects research permission and participants’ informed consent were obtained. Participants included the European man instructor of this 16-week course at a large, public, rural U.S. university, and 17 of his beginning-level FFL students—most full-time undergraduate stu- dents in their 20s or late teens.2 Some university programs required foreign language coursework; many did not.

Data Collection

Thirteen 50-minute class sessions were observed and recorded with a camcorder, camera, field notes, and two audio recorders. Fol- lowing focal-student recruitment (Laila, Celine, and William, in Week 4), their three desks also had audio recorders; they represented different races, genders, in-class participation levels, course grades, and time-related university experience. All student participants completed a background survey. Two 30–45-minute focus groups included six and seven students. Focal students and the instructor completed 1–2 semiguided interview(s) (30–60 minutes), involving background questions and materials-related recall.

Analysis

Transcriptionists transcribed recordings of all classes, interviews, and focus groups for spoken language. Then, similar to Canagarajah’s (2018) polysemiotic analysis, I exploratively studied all audio-video recordings, interviews, photographic documentation, material texts, and transcripts— until inductive analytic saturation was achieved (Saunders et al., 2018). This preliminary analysis involved (a) classroom interaction analysis to identify both frequent and unique discourse patterns, and (b) textual analysis of materials to identify common and unique traits (e.g.,design features, task types). One frequent and general pattern of materials-in-interaction emerged along with small ‘pockets’ of relatively infrequent patterns of materials-in-interaction. The latter were characterized by diverse discursive and material traits.

Analysis then focused on unpacking all these patterns. However, additional analytic methods were needed—beyond polysemiotic analysis of discourse and materials—to capture (a) the dynamic multidimensionality of materials use, and (b) differences and similarities in the patterns of materials use. Initially, research focused on analyzing materials-in-interaction, but eventually refocused on materials-in-action. As Sørensen’s (2009) sociomaterialist methodology explains, “introducing a new dimension (. . .) [such as the] material (. . .) into learning theory is not only a matter of taking (. . .) [that] additional element into account (. . .) [Rather] such a step changes the whole methodology” (p. 5). Action under- pins the present study’s main substantive and conceptual issues (see Table 1), bridging the data’s linguistic and material dynamics. For all these reasons, the methodology incorporated action analyses.

Action analyses first explored frequent, unique, or otherwise salient ‘action chains’ comprising classroom interaction and activity (following Scollon, 2001). For example, a student asking a question constitutes the following action chain: (a) student raises hand, (b) teacher acknowledges student, then (c) student utters question. Each such overarching action was then broken into ‘lower level’ component actions. For instance, action (b), ‘teacher acknowledges,’ might include: teacher glances, nods head, then calls on student. Then, I conducted ‘action diagramming,’ capturing the three-dimensionality of classroom activity (de Freitas, 2012; Tejkalová, 2007). Diagramming systematically focused on visually representing the materials and observable actions (e.g., linguistic, social, physical). Each action chain type and diagram type served as a sort of complex coding category, though no two were exactly the same.

All these action chain and action diagram analyses were integrated with the aforementioned polysemiotic analyses of discourse and materials. Procedurally, action analyses and polysemiotic analyses were sometimes distinct, sometimes overlapping. As a whole, these methods can be described as ‘polysemiotic action analyses,’ which loosely resemble Zheng et al.’s (2012) “rich visualizations of action and interaction patterns” (p. 340). The findings represent analyses as polysemiotic transcripts (i.e., excerpts) and as classroom action diagrams. (The Appendix contains language-related transcription conventions.)

Throughout the entire process, I returned continuously to the original audio-video recordings of classroom interaction and the original materials or photos thereof, while also moving iteratively among transcripts, fieldnotes, interviews, focus groups, and action analyses (diagrams and chains). Finally, another materials-use researcher holistically confirmed the accuracy of the action diagrams and polysemiotic transcripts presented here. Like Canagarajah’s (2018) sociomaterialist methods, the findings present both close and narrative analyses that emerged in response to the RQs. Identifiable images of participants appear only when necessary (see Wiles et al., 2008).

FINDINGS

The instructor, Edgar, created nearly all the classroom materials, finding them “more personal” than the “boring” textbook “activities” (Interview, 2 October 2015). The required textbook was rarely used—primarily for vocabulary instruction and as a student reference text. Edgar also explained: “[My graduate school classmates and I learned to] come up with (. . .) [our] own material (.. .) It (.. .) stuck [and is]… (.. .) always what I’ve been doing.” Thus, the teacher-created materials along with the whiteboard were the most commonly used in this FFL class. Regarding course goals, syllabus objectives targeted ‘the four skills’ (listening, speaking, reading, writing), and gram- mar topics structured the calendar. Students perceived the course foci as “basic grammar (. . .) and vocab” (Focus group, 6 October 2015). Additionally, Edgar reported aiming for them to “[use] French for communicative purposes” (Interview, 2 October 2015).

This research examined classroom-based materials use (i.e., ‘materials-in-action’) through the lens of pedagogical ergonomics, which focuses on intra-actions between LLT materials and the students/teacher. One pattern of materials-in-action prevailed in this classroom: initiation–response– feedback (IRF) sequences involving board work and form-focused worksheet materials. Inter- mittently, small ‘pockets’ of different patterns of materials-in-action characterized the class- room activity and interaction. The first findings section focuses on the prevailing pattern of materials-in-action and develops the pedagogical ergonomics framework (RQ1), which the subsequent analyses then draw on. The second findings section’s macro-level analysis (RQ2) reveals four genres of materials that generally structured classroom activity. The final findings section’s micro-level analysis (RQ3) presents three different polysemiotic patterns of intra-action, linking specific features of particular materials to the moment-to-moment action (e.g., interaction) that they induced.

Pedagogical Ergonomics of Materials Use

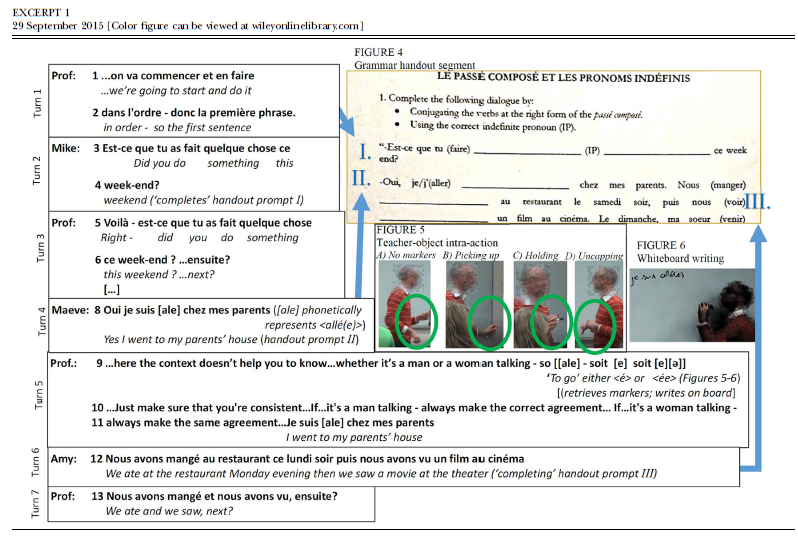

Taking intra-action—pedagogical ergonomics’ core construct—as the departure point, this first findings section addresses RQ1: What is pedagogical ergonomics, as related to LLT materials use? The section uses the most frequent pattern of materials-in-action in this classroom—IRF sequences involving board work and form-focused worksheets (see Excerpt 1)—to flesh out this framework and exemplify why intra-action is conceptually useful.

Intra-Action. As mentioned previously, the concept of intra-action explains sociomaterial ‘happenings,’ such as that in Excerpt 1, where students, the instructor, and the materials intra- acted. To summarize this intra-action: Students conjugated worksheet verbs in the passé composé past tense and inserted pronouns in the blanks (see Figure 4), as the teacher guided this and intermittently wrote feedback on the whiteboard (see Figures 5 and 6).

Like the concept ‘interaction,’ which can com- prise just two turns or a long exchange, an intra-action may be brief or extended. Nonetheless, intra-action differs in important conceptual ways from interaction. Regarding the former, Figures 5 and 6 entailed a brief intra-action between Edgar and the marker: He influenced it (e.g., lifting it, removing cap), and it enabled him to write. As illustrated here, language classroom intra-action refers to influences or engagements among diverse entities or beings, animate or inanimate. Conversely, interaction—like the talk between Maeve and Edgar (Excerpt 1, 8–11)—is a semiotic exchange between animate beings, namely humans (cf. Engman & Hermes, 2021, this issue).

While conceptually distinct, in reality intra-action and interaction are entangled. Turns 4–5 are again illustrative: The passé composé paradigm requires subject–verb gender agreement when conjugating some verbs, like aller ‘to go’ (Figure 4, II). The options are: allé (masculine) and allée (feminine), whereby the feminine marker is the word-final e. In line 8, Maeve would typically conjugate aller in the first person in accordance with her feminine gender. When Maeve spoke her response [ale], the grammatical gender was ambiguous because this word-final e is silent for this French verb, although it appears in writing. Therefore, Edgar transcribed Maeve’s utterance onto the whiteboard (Figure 6; Excerpt 1, line 9). Meaning, the intra-action between Edgar and the marker enabled him to explain this grammar and continue the interaction with the class. The human–object intra-action was entangled with the human-to-human interaction, as is arguably the case with materials use in language classrooms worldwide. Moreover, interac-tion is a type of intra-action, since interaction involves (semiotic) action among interlocutors who thereby influence one another—which fits the definition of intra-action.

As mentioned (Table 1), action is conceptually foundational to both intra-action and interac-tion. In ergonomics, a given action can be social, material, and/or cognitive. These three dynamics also characterize intra-action: For example, Mike answered a request (Turns 1–2; the social), using the handout and his articulatory organs (the material), while conjugating the verb faire ‘to make’ (the cognitive). Thus, intra-action— and by extension, the framework of pedagogical ergonomics—focuses on what happens in the language classroom without unnecessarily privileging any particular social, material, or cognitive dynamic. Language is also social, material, and cognitive in nature; meaning, these three dynamics of ergonomics theory subsume linguistic action—as well as other types of action.

Actants. As Excerpt 1’s happenings unfolded, certain beings and things were foregrounded and others backgrounded. These are conceptualized here as ‘actants.’ For instance, while the white- board (Figure 6) was not an actant in Turns 1–4, it was in Turn 5. ‘Actant’—the second concept in the pedagogical ergonomics framework—refers to human or nonhuman entities or beings (e.g., teacher, students, materials) that take part in the intra-action. Time helps define this construct (see Larsen–Freeman, 2014): An entity or being is an actant only when it intra-acts with another entity or being. Following Sørensen (2009), the concern is not the actant unto itself, but rather actants’ participation in the ‘happening’ in question.

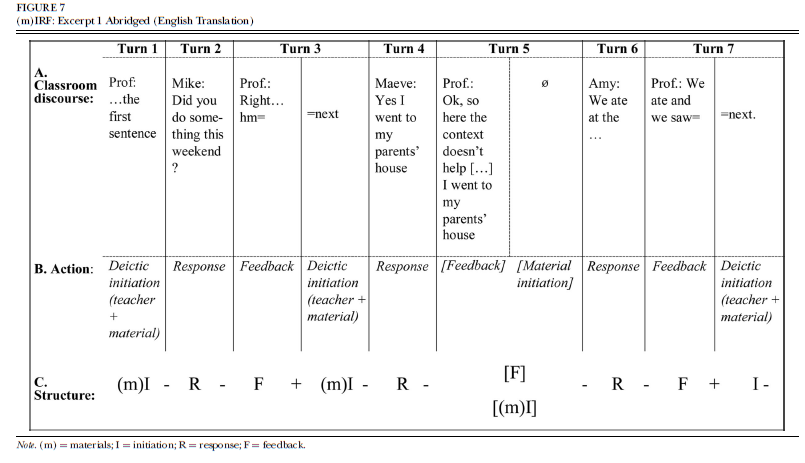

Conceptualizing an inanimate material as an actant is somewhat revolutionary in language education scholarship (cf. Canagarajah, 2018; Matsumoto, 2018; Toohey, 2018). Nonetheless, intra-actions involving the handout (Figure 4) offer further evidence that materials were actants. Excerpt 1 ostensibly exemplifies the widely studied IRF sequence, which previous research overwhelmingly views as teachers and students engaging one another. However, the handout was also an actant here. Analysis of spoken discourse (Figure 7, Row A) and IRF actions (Row B) shows how the material and the teacher jointly initiated IRF sequences. The material’s prominence was evident in spoken deixis referencing hand- out prompts (e.g., “the first sentence” [Figure 7, Turn 1; Figure 4, I] and “next” [Figure 7, Turn 3; Figure 4, II]). Without the materials’ linguistic meanings and forms, the instructor’s initiation utterances here would be nonsensical. Thus, these were not merely IRFs—where I canonically means ‘teacher initiation’—but rather (m)IRFs, where m refers to ‘material’ (Figure 7, Row C).

Other (m)IRF sequences were initiated primarily by the material rather than the instructor, as in Turn 5 (Figure 7) for handout prompt III (Figure 4). Student Amy (not shown in Turn 5) preemptively volunteered for this handout prompt, and this (m)IRF initiation (Turn 5) unfolded within 3 seconds, as follows: The instructor glanced up while repeating feedback for the previous prompt (Figure 4, II), seeing Amy’s self- nomination gesture for the next. Edgar flicked his hand, affirming her self-nomination. She then verbally ‘completed’ prompt III (Turn 6). Meaning, the material, student, and eventually the instructor exercised distributed agency in advancing the intra-action, yet the material’s content, forms, and structure ultimately triggered this initiation.

Many teachers have likely had similar experiences with students like Amy ‘reading forward’ in the activity material (Hasegawa, 2021, this is- sue). Amy almost certainly anticipated the question (Figure 4, III) owing to her familiarity with the conventions of classroom space. Indeed, intra- action always “takes place as part of a much larger (. . .) system” or context (Wilson, 2000, p. 564). Thus, ‘space’ is pedagogical ergonomics’ third foundational concept.

Space. Conceptually, space subsumes and ex- tends beyond cultural, social, and political context to also involve physical dynamics (Canagarajah, 2018; Miller, 2012). To understand ‘what happened’ in this classroom—the study’s central goal—space must also be analyzed (Canagarajah, 2018). Classrooms’ physical–spatial dynamics are especially overlooked in research and most transcription conventions. Materials themselves clearly have important physical traits (Figure 4), like the handout’s repeated sign of a print line with negative textual space above—‘blanks.’ As with widespread classroom norms, this physical– textual sign prompted participants to ‘conjugate’ adjacent parenthetical forms (Excerpt 1).

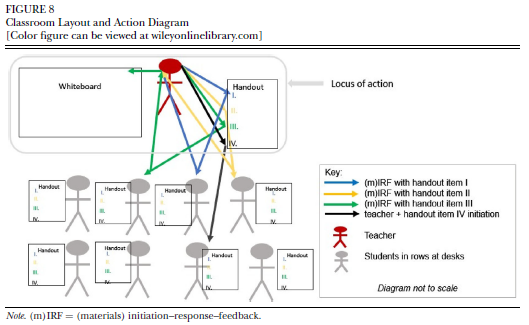

Another salient physical–spatial dynamic was the classroom layout, depicted in Figure 8, where arrows represent linguistic action—the flow of turns-at-talk. Clarifying ‘what happened’ in this intra-action in ways that Excerpt 1 cannot, this representation illustrates (a) how the handout anchored continuous interlinking (m)IRF ‘chains’ and (b) how the teacher, the handout, and to a lesser extent, the board were the ‘loci of action’— meaning, sociomaterial foci of activity. Other classroom individuals, space, and resources were thereby rendered more peripheral, and students’ actions limited.

This general type of space is conceptualized here as ‘classroomscape,’ meaning the school-room where the material world and humans intra-act. Classroomscape is ontologically similar to the concept ‘space,’ though narrower in scope. Few classroom-based studies from language education focus on classroomscape (Rajaee Pitehnoee, Arabmofrad, & Modaberi, 2020).

Concentrating on the classroomscape instead of space in general allows for a sharper focus on this particular physical, sociocultural, and political setting. Drawing on ergonomics concepts (Pheasant, 2003), the classroomscape includes tangible—oftentimes measurable—bodies, structures, and objects. Some inanimate physical aspects are relatively stable and enduring—like the floorplan and nailed-in whiteboard—while bodies therein are dynamic and shifting. Nonetheless, like the sister concept of space, classroomscape is not a physical ‘shell’ (see Miller, 2012; also Brown, 2005; Laihonen & Szabó, 2018, on schoolscape). To the contrary, intra-actions and even actants are co-substantiated with and through the classroom-scape. For instance, this teacher-fronted class-roomscape configuration was not inherent to this physical room (Figure 8; Excerpt 1); instead, Edgar and the (less powerful) students and mate- rials enacted this classroomscape to be ‘teacher- fronted.’ However, the classroomscape also influenced the actants and their intra-actions. For example, the traditional layout of desks likely promoted the teacher-fronted intra-action (Muñoz, 2014) and the conventions of this institutional educational space prompted Edgar to assume the role of pedagogical authority.

Moreover, the classroomscape’s boundaries were permeable, particularly vis-à-vis its social, cultural, and political dynamics. The intra-action around grammatical gender exemplified this (Excerpt 1, 8–11) since the closely related social construct of gender is clearly not confined to the classroom but much more far-reaching. Physically, the infinitive verb form aller ‘to go’ appeared in this intra-action via the material prompt (Figure 4, II), then its masculine (i.e., allé) and feminine (i.e., allée) conjugations were inscribed upon the board (Figure 6). Yet grammatical gender was not merely a textual or linguistic dynamic residing in classroom materials. Gender was also part of the participants’ sociocultural identities, which impacted how this verb could be formed and understood.

These data suggest that teachers might enhance their pedagogy by remembering that LLT materials are inextricably entangled with—not separate from—learners’ lived space. For example, some students reported feeling confused by the instructor’s ‘dismissal’ of Maeve’s gender as the ostensible subject of aller and the lack of clear gender agreement for a verb requiring it (Excerpt 1, Turns 4–5). Alternative activities and materials on grammatical gender could perhaps better allow students to connect the forms with real gendered beings—including themselves.

Such observations have theoretical and practical implications, pursuant to these dual aims of pedagogical ergonomics. This is particularly important seeing that (m)IRF chains were the most common pattern of materials-in-action in this classroom. Moreover, this type of worksheet material is pervasive in foreign language class- rooms worldwide, according to Tomlinson and Masuhara (2018).

To conclude, this section fleshes out the conceptual framework of pedagogical ergonomics as intra-action among actants that is co-substantiated with sociocultural, political, and physical space. Importantly, pedagogical ergonomics analysis equally prioritizes material, social, and cognitive dynamics, unlike most language education research, which neglects the material. Moreover, in light of this pedagogical ergonomics analysis, ‘materials use’ is defined here as: classroom action involving emergent influences, engagements, and exchanges among LLT materials, one or more learner, and often also the teacher—situated in a physical, sociocultural, and political space. The pedagogical ergonomics framework is deployed and further developed throughout the rest of the findings.

Macro-Level Patterns: Overview of Student and Teacher Intra-Actions With Materials

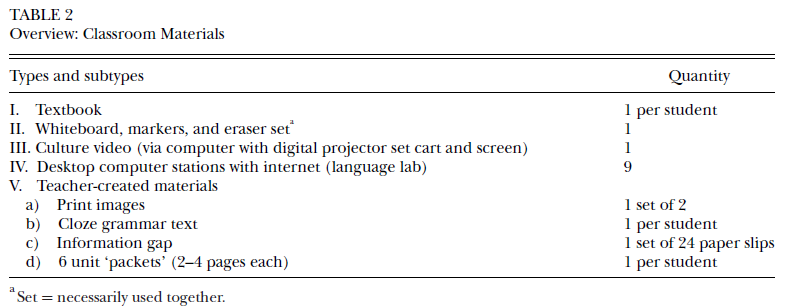

This second findings section shifts to a broader analysis by taking into account all the materials used in this class (Table 2) and explaining key overarching ways that materials structured activity. Specifically, this section addresses RQ2: What were general types of ‘materials use’ in this FFL class, as revealed through macro-level analysis of classroom activity?

Analysis of intra-actions among students and all the materials observed (Table 2) is arguably an important first step toward understanding what they learn from these (see Larsen–Freeman, 2014). This analysis revealed a typology of four common types of materials use (Table 3): universal, communal, distributed, and responsive materials-in- action. Each describes a macro-level pattern of classroom action that particular types of materials induced. Lines in each illustration (column C) represent intra-actions (i.e., engagements, exchanges, and/or influences). The teacher at times participated in these intra-actions, at other times less so.

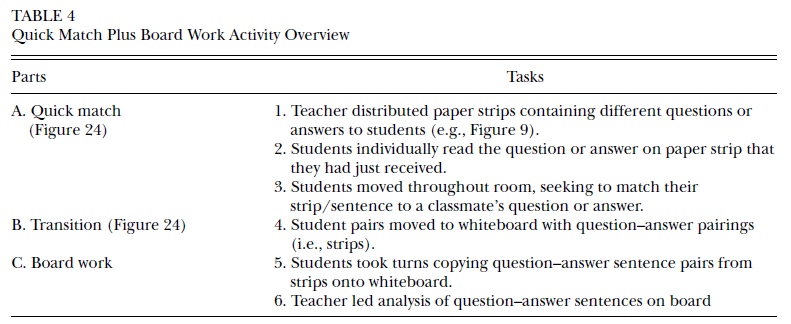

Most materials used were universal and communal (Table 3, Rows I and II). An example of the former—the handout—appeared in the previous findings section (Figure 4). Moreover, the prevailing pattern of materials-in-action—(m)IRF chains—often involved a communal material, the whiteboard (Figure 6). Additionally, observed just once, distributed materials (Table 3, Row III) included teacher-created information gap texts (Figure 9). Half of these paper slips contained questions in French and the other half the cor- responding answers. Each student received one slip, then searched for the classmate with the matching question or answer. Also observed just once, though reportedly used several times in un- observed class sessions, responsive materials (Table 3, Row IV) included a Web site called Que Faire à Paris? ‘What to do in Paris?’—which students navigated individually or in pairs as a class-time computer lab activity.

Each type of materials use (i.e., universal, com- munal, distributive, responsive; Table 3) is a “material pattern” of classroom objects’ dynamic “entanglements” in “everyday practice” (Fenwick et al., 2011, p. 1). One salient aspect of this was how information was physically organized in the materials vis-à-vis the task at hand. For example, distributed materials uniquely delivered different information across varied physical resources (Figure 9). (Somewhat supporting previous research on information gap materials, these afforded students the opportunity to interact in French, albeit with mixed outcomes, discussed in next section). A contrasting type, responsive materials’ dynamic content changed via exchanges between the student(s) and Web site (e.g., mousing, computer processing). In contrast, information in universal and communal materials was available to all students but in physically different ways: The communal whiteboard (Figure 6) enabled the instructor to spontaneously provide students with the same visual information via this one physical entity, while each student had their own copy of a given universal material (Figure 4; also Figure 8). In sum, each such type of material-in-use physically configured its content different: These dynamics constituted the materials’ ‘informational physicality.’ These were not “minor fluctuations” (Fenwick et al., 2011, p. 24) but rather material practices with learning implications: for instance, these affected the social dynamics of the class- room activities, as described in Table 3 and later in the third findings section.

Generally speaking, each type of materials use (i.e., universal, communal, distributive, responsive) captures an aspect of the resources’ (Ta- ble 2) ‘materiality,’ meaning “that which matters about an entity” (Hafermalz & Riemer, 2015, p. 2). Otherwise put, ‘materiality’ references what was most salient about a material during a classroom intra-action with students and teacher. Thus, Table 3 captures the ‘language pedagogy materiality’ of these materials-in-action (Table 2).

These material patterns (Table 3) can be described as modalities of materials use. Set- ting aside its linguistic connotations, ‘modality’ refers simply to the mode or manner of action (Random House, n.d.). Alternatively, these four types (Table 3) can also be understood as gen- res of classroom materials. ‘Genre’ refers to physical, visual, linguistic, and ‘paralinguistic’ features, which relate to its paradigmatic us- ages (see Johnson & Johnson, 1998). Meaning, the genre of material seemed to dictate—and overlap with—the modality of action for each type of materials use (Table 3). The difference between the two constructs relates to what aspect of the material-in-action is in focus—the mate- rial (i.e., genre) or the action (i.e., modality). While the concept ‘materials use’ necessarily involves both materials and action (i.e., materials- in-action; Guerrettaz et al., 2021, this issue), ontologically the notions of ‘action’ and ‘material’ themselves are distinct. This allows analysis to sometimes focus more on the action and at other times the material. The discussion and conclusion will revisit these concepts—‘genre of material’ and ‘modality of use.’

Many teachers likely recognize universal, communal, distributed, and responsive materials in their own practice, though these have gone unrecognized in research. These modalities or gen- res are pedagogical ergonomics concepts because they reflect patterns of intra-action among human and material actants. These are arguably foundational dynamics of how language classrooms work. The next section analyzes in-depth examples of universal, communal, and distributed materials- in-action.

Micro-Level Patterns of Materials-in-(Inter)Action

The previous findings section presented over- arching patterns of materials use (Table 3). This third findings section examines detailed features of individual materials in moment-to-moment interaction and activity. Drawing on pedagogical ergonomics concepts from the prior sections, this final overarching findings section responds to RQ3: What micro-level patterns of materials- in-action emerged, and what language learning opportunities did these intra-actions involve? This analysis takes into account the participants’ and syllabus’s meaning- and form-focused language learning goals. Tending particularly to the impacts of materials on classroom discourse, three polysemiotic patterns of materials-in-action are presented.

As mentioned previously, one pattern of materials-in-action prevailed in this classroom: (m)IRF chains (e.g., Excerpt 1). Throughout the 13 classes observed, amidst long stretches of (m)IRF chains, small ‘pockets’ of different patterns of classroom activity intermittently emerged. This findings section first examines the (m)IRF chains in depth, presenting an ex- ample of universal materials involved therein. The second pattern highlights a simple set of communal materials, explaining how these effectively promoted students’ speaking of French. The third pattern details a rare example of distributed materials from this class—information gap resources—and their unexpected outcomes with regard to target language interaction.

Micro-Level Pattern 1: Fractal Mapping of Student Utterances Onto a Universal Material. This section further unpacks the intra-action in Excerpt 1 (also Figure 8) from the first findings section on the pedagogical ergonomics framework. This overarching type of materials use—completing a form- focused fill-in-the-blank text—involved a complex micro-level action pattern. As explained previously, it consisted of (m)IRF chains (Figure 7) ‘anchored’ by the worksheet text (Figure 4). Additionally, handout symbols and text ‘mapped onto’ students (Figure 8): The teacher guided and the material structured this. ‘Mapping’ refers to a linking of “each element of a set” (i.e., material prompts) “with another element of another set” (i.e., students in the class; Lexico, n.d.-c). Focal student William similarly explained: “We go down the line a sentence at a time, taking turns (. . .) Everybody (. . .) does a little bit (. . .) even if they don’t raise their hand” (Interview, 15 December 2015). This mapping pattern can be character- ized as ‘fractal,’ which refers to a weblike, semi- random, turn-taking structure “in which similar patterns recur (. . .) progressively” (Lexico, n.d.- b), illustrated in Figure 8. Moreover, the student language was ‘restricted’—limited in quality and quantity (Wardhaugh & Fuller, 2015). Considering all these characteristics, this pattern of material(s)-in-action constituted a ‘fractal map- ping’ of student utterances onto the worksheet.

In addition to being a locus of action, as the first findings section describes, this universal material was also the ‘focal plane’ text. A focal plane is a two-dimensional entity at the epicenter of class- room activity. Numerous other intra-actions involved focal planes (e.g., whiteboard, projector screen).

From a pedagogical ergonomics perspective, physical texts such as these (Figure 4) occupy measurable space (Cowley, 2012). The static na- ture of written text contrasts more dynamic spo- ken language, which includes “bodily skills (. . .) [and] vocalizing (. . .) activity” (Cowley, 2012, p. 21). While such physical differences in writing versus speaking have received considerable scholarly attention, how these shape language class- room interaction has not. The focal plane text (Figure 4) was physically located ‘outside’ the students, which contrasted activities whereby language emerged from ‘inside’ the learners (following Sørensen [2009], who offers ‘choral singing’ as an example of the latter). Furthermore, in Excerpt 1, students’ language production was prescribed by the handout. The fractal mapping of (m)IRF chains reflects these qualities of the material and task. The text located ‘outside’ learners (i.e., Figure 4) was the most ‘prominent’ language in the classroomscape, arguably more so than language ‘inside’ students (following Sørensen, 2009). Accordingly, their actions were directed to- ward the external focal plane text, as Figure 8 shows.

Completing a cloze form-focused worksheet is arguably a widespread sociomaterial practice in foreign language education worldwide. Teachers deploying such materials in their classrooms may find insights from this type of intra-action analysis to enhance their pedagogy. This pattern of materials-in-action afforded students opportunities to read aloud, listen, interact with Edgar, and form targeted grammar. However, if communication is a goal, like Edgar reported, adapting ma- terials and uses thereof that prioritize language that emerges from ‘inside’ learners (borrowing Sørensen’s [2009] term) may be a useful starting point. An example of such a material-in-use is discussed next.

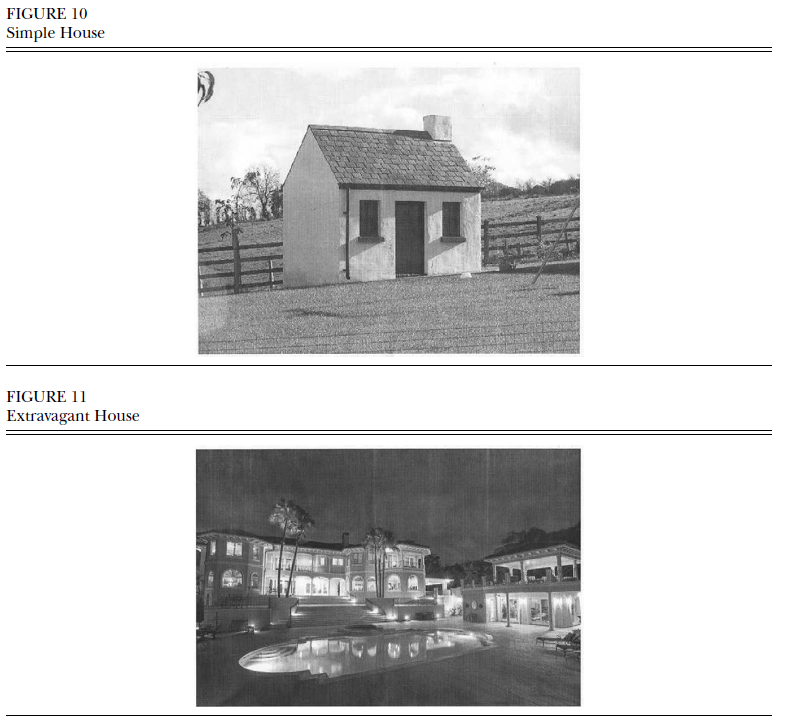

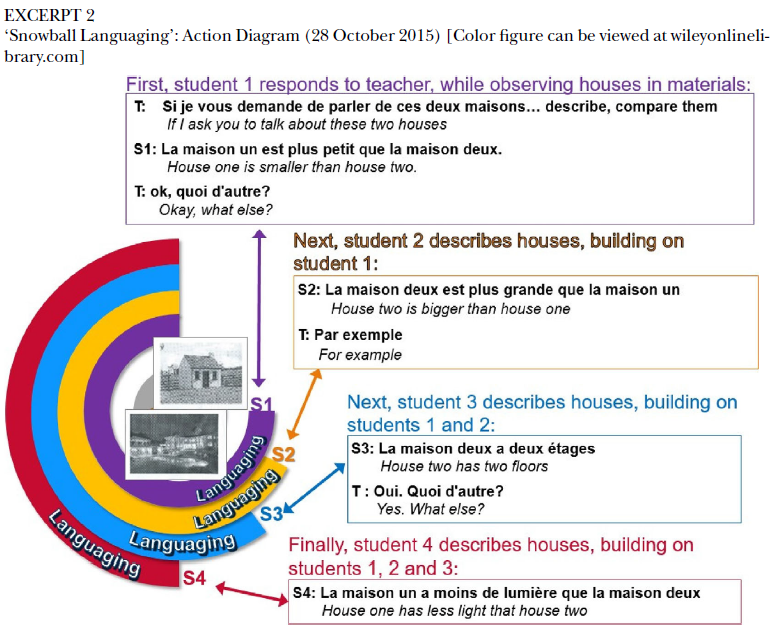

Micro-Level Pattern 2: ‘Snowball Languaging’ Around Communal Materials. This subsection of findings further responds to RQ3. This second micro-level pattern of materials-in-action was a rare instance where students spontaneously used meaning-focused French, and is thus of potential practical interest to readers. The materials were two full-page (8 × 10 in) still images of houses (Figures 10 and 11). Standing at the front of the classroom, the teacher displayed both side-by-side for the students, asking them to describe the images using comparative forms (e.g., plus ‘more,’ moins ‘less’).

Similar to the Figure 8 classroomscape, these materials (Figures 10 and 11) similarly functioned as focal planes. Moreover, student and teacher language was structured through (m)IRF chains in both Excerpts 1 and 2. However, Excerpt 2 involves ‘elaborated’ rather than ‘restricted’ student language (following Wardhaugh & Fuller, 2015)—more extensive linguistic action by students occurred here than in Pattern 1 (the ‘fractal mapping of utterances’). Therefore, this action diagram (Excerpt 2) concentrates on these salient dynamics of these materials-in-action—classroom language and actants (i.e., materials, teacher, stu- dents).

This polysemiotic action pattern—‘snowball languaging’—describes how students produced language ‘around’ materials (Excerpt 2). ‘Snow- balling’ means “to increase, accumulate, expand, or multiply” (Merriam–Webster, n.d.). ‘Languaging’ is meaning-making whereby language is considered a process, not an object (Cowley, 2012).

The general physical characteristics of this set of communal materials were simple: two black- and-white images on paper. However, the images themselves were detailed and complex (Figures 10 and 11), and followed the unit theme—la maison ‘the home’—which had seemingly prepared students with language for this task. Learners intra-acted with the images, observing and describing their rich visual content that determined the overarching theme of student talk (Excerpt 2). Nonetheless, the specific content of unfolding talk was unpredictable, progressively building as student respondents listened to previous speakers then voiced their own spontaneous description. In sum, the materials and task required a focus on unfolding language use. Students generated language from ‘inside’ themselves, in contrast to Excerpt 1 (Figure 8) where the most ‘prominent’ classroom language was physically located ‘outside’ the learners (borrowing from Sørensen, 2009) in the form-focused worksheet (Figure 4). At least three students praised what they described as “visual” materials like Figures 10 and 11, using almost the exact same words (e.g., “I am more of a visual learner,” Rose, Focus group, 6 October 2015). Laila described such materials: “↑See see - this is exactly what I love because (. . .) it (. . .) really shows you stuff that you can recognize (. . .) (. . .) [it] really stands out” (Interview, 15 December 2015).

In the snowball languaging (Excerpt 2), the content of classroom talk was visually tangible in the materials—concretely palpable to the learners. In this activity, the instructor integrated this ‘visual content’ of the images with the classroom space, physically transforming and engineering it in meaning-rich ways. This contrasted Excerpt 1, where the handout dialogue was abstracted from students’ lived space, clashing with one student’s own gender. All the aforementioned characteristics of the materials use in Excerpt 2 seemed to enable students to produce French-language descriptions, which is often difficult at beginning levels (American Council of Teachers of Foreign Languages, 2012).

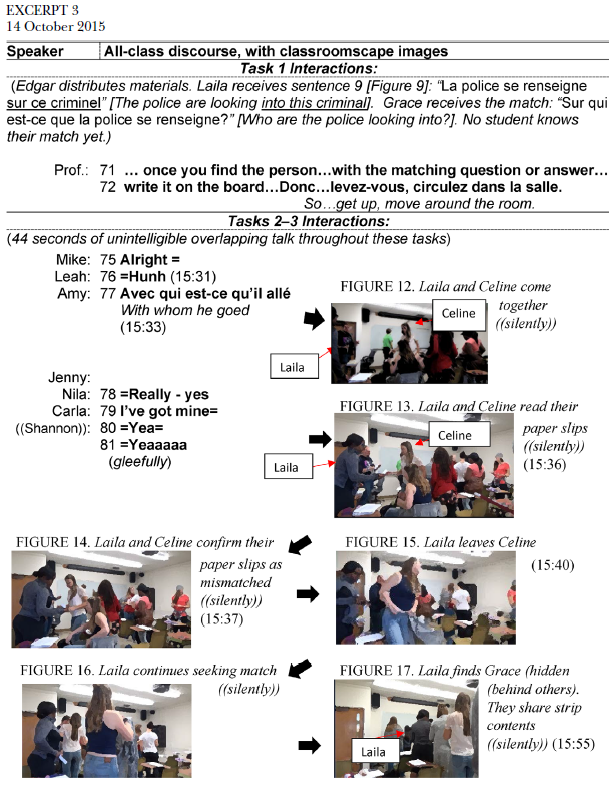

Micro-Level Pattern 3: The Quick Match of Distributed Materials. This final analysis concludes the response to RQ3 by presenting a third pattern of materials-in-action: the ‘quick match.’ This involved distributed materials (e.g., Figure 9) and physically dynamic activity. Such a pattern was observed once in class, and richly contrasts Pat- terns 1 and 2. Additionally, this ‘quick match’ pat- tern offers insights into language pedagogy by exemplifying unexpected outcomes of information gap materials, which are often viewed as ideal for promoting L2 interaction (Richards & Renandya, 2002).

In this intra-action, learners moved around the classroom using the information gap materials (e.g., Figure 9). Arguably, this was the type of “fun and interactive” “group [activity]” and “game” that several students reported enjoying (Focus group, 6 October 2015). The focal pattern of materials-in-action—the ‘quick match’—was part of a broader sequence of tasks (Table 4).

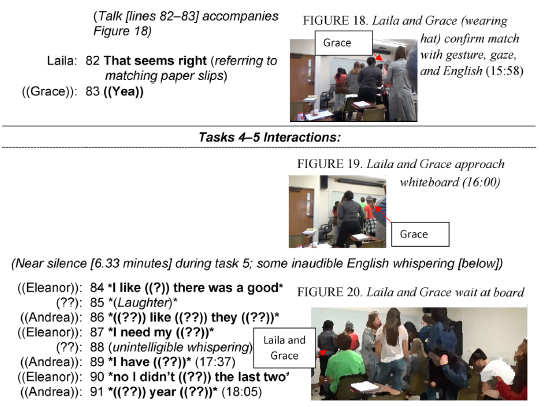

The matching (Table 4, Task 3) was the main part of the activity but finished rapidly, in 44 seconds. Moreover, field notes and recordings indicate that little French was used. Task 5—which involved students waiting at the board mostly silently—lasted 8 times longer (6.33 minutes). This intra-action analysis helps unpack these two unexpected outcomes of these materials-in-use: (a) the lack of French use for Task 3’s information gap activity, and (b) the long lull during Task 5.

Excerpt 3 includes nearly all audible quick- match-plus-board-work interaction, and is organized around Table 4’s component tasks. (Thick arrows show the sequential flow of activity.) Since focal students, and Laila in particular, were recorded more clearly here than general student participants, analysis highlights her intra-actions. During all 11 minutes of Excerpt 3, Laila’s meaning-making was mostly silent and embodied (Figures 12–23)—involving gesture, gaze, and reading of classmates’ paper slips. She briefly uttered French once (114) and English twice (82, 98). While a few students spoke French (e.g., Amy, 77), many did not. One student conversed on her phone in English during the long Task 5 lull (Figure 20).

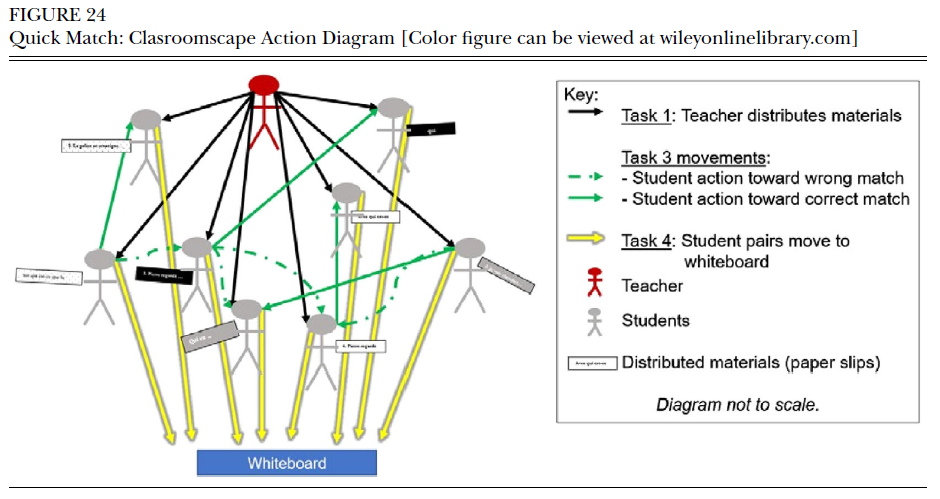

Regarding the first unexpected outcome, these findings complicate the influential literature on information gap activities since these materials did not promote much interaction in French. Nonetheless, plenty of intra-action occurred during the quick match. Figure 24’s lines represent participants’ physical movement, illustrating unpredictable and dynamic student action. These student-driven actions might suggest that they wielded more agency in the quick match, com- pared to the lockstep (m)IRF chains in Pattern 1 (e.g., Figure 8). Nonetheless, students did not seem to exert much agency for speaking French during the quick match.

Agency always involves purpose (Guerrettaz et al., 2021, this issue), and the information gap design (Table 4, Task 3; Figure 24) embodied two seemingly congruent purposes: (a) the teacher’s language learning purpose for students to speak French, and (b) the sociophysical purpose of stu- dents matching paper slips. The latter reverts to the materials design, which was engineered to support the former. While students accomplished the sociophysical purpose (i.e., the matching), many did so through English and gesture (Excerpt 3), thus thwarting the language learning purpose.

The instructor remarked, “The idea [is] for them to (. . .) use French as much as possible, but (. . .) it is not necessarily what happens (. . .) some students (. . .) are really (. . .) struggling with French (. . .) so it’s really hard for them to do this” (Interview, 9 March 2016). In focus groups, several learners confirmed their proficiency-related challenges. As Laila explained, “Even (. . .) basic conversation [in French is] hard” (Interview, 17 November 2015). Other considerations may have also contributed to students’ disuse of French. Specifically, English was the established communicative language of this space, even though the instructor frequently requested that students use French. In a focus group, Deidre asserted, “Seriously—every time (. . .) [our instructor says] ‘work with a partner’ (. . .) then it’s (. . .) dead quiet” (6 October 2015). A focal student, Celine, elaborated, “It’s weird (. . .) I would feel kind of snotty (. . .) all the sudden (. . .) whipping out (.. .) French (.. .)I would be (.. .) judged [by my classmates]” (Focus group, 6 October 2015).

Pedagogical ergonomics also helps explain the second unanticipated outcome of these materials-in-action: the long lull in Task 5. Similar copying practices are ubiquitous worldwide (e.g., Sayer, 2019); thus, this is worth unpacking. Task 5’s primary underlying purpose was converting the distributed materials into a communal text for form-focused analysis, particularly evident in lines 97–115 (Excerpt 3). The impetus behind this ‘conversion’ activity may have stemmed from participants’—namely Edgar’s—proclivity for form-focused universal and communal materials, the most prevalent modalities of materials use in this class. This suggests that such materials-use conventions were powerful: Even when Edgar innovated to create and deploy distributed materials, in the end he still had students use these for form-focused analysis via his most frequent communal material (i.e., the board). Task 5’s slow pace seemed physically caused by the white- board’s small size relative to the large number of students attempting to use it (Figures 17–21 and 24). The physical lack of dedicated instructional technology (e.g., a fixed digital projector and computer) inhibited Edgar’s typical use of such tools (Interview, 2 October 2015). Thus, in- stead of Edgar quickly projecting digital copies of the information gap materials, which he shared with me, they had to use the whiteboard. Such seemingly mundane details often majorly affect classroom realities. Here, this resulted in 6.33 minutes of class time being spent in near silence as students converted the board into a communal text.

Ultimately, the outcomes of an activity like this information gap do not depend solely on the materials or task design. Agency was distributed across materials, task design, student abilities, and space. Indeed, space itself has agency (Miller, 2012), and salient agentive dynamics of space here included the class’s established patterns of English communication, the lack of readily available instructional technology, and the teacher’s dominant modalities of materials use, observed over the duration of the semester. Thus, distributed agency is again critical to understanding materials use. Despite the two seemingly unexpected outcomes, various language learning opportunities arose during the quick-match-with- board-work task sequence. Students analyzed and discussed grammar and read and copied French sentences; Edgar’s spoken French offered listening opportunities.

To conclude this third overarching findings section, these micro-level patterns of materials use included: the ‘fractal mapping’ of student utterances onto form-focused worksheets (Pattern 1); the ‘snowball languaging’ that enabled these beginning-level learners to use meaning- focused French (Pattern 2); and, the quick match information gap activity (Pattern 3). These polysemiotic action analyses reveal how and why salient examples of classroom activity unfolded in particular ways vis-à-vis the materials. Similar materials and such issues of common, effective, and/or unpredictable materials use likely affect many other foreign language classrooms in comparable ways.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Sociomaterialism is often viewed as the study of how and why “matter matters” (Barad, 2007, p. 64). Taking this a step further, the present study seeks to understand how classroom ‘happenings happen.’ Classroom activity and interaction can arguably be distilled down to the two foundational dynamics at the heart of this study: materials and action.

To summarize, this article explores a neglected area of language education research by theorizing and analyzing classroom-based materials use—conceptualized as materials-in-action—and deploys pedagogical ergonomics to qualitatively explore and unpack examples with definite pedagogical implications. The pedagogical ergonomics framework (a) comprises entangled intra-actions among human and material actants with classroom space, and (b) is the study’s main theoretical contribution. Primary substantive findings include the four genres or modalities of materials-in-action and three micro-level patterns of materials-in-action. These qualitative substantive findings, though not generalizable, resonate with other research and ample anecdotal evidence from other pedagogical contexts. Given that few studies have examined materials use, expanding this line of research to other class- room activities, interactions, and spaces would be beneficial.

Action is foundational to this article’s foci, theory, methods, and analyses. Action analysis of materials use dexterously allows integrated study of the physical, spatial, temporal, linguistic, sociocultural, political, and cognitive dynamics of class- room interaction and activity. Both the substantive topic of materials use and the methodology that this required—polysemiotic action analysis— are relatively new to language education. Such developments here recall how analytic innovations for researching computer-assisted language learning (CALL) similarly emerged with that field in the late 20th century, including, for example, scalar charting of time and virtual space to study novel topics from that subfield (e.g., interface, user experience; Beatty, 2013; Zheng et al., 2012).

Pedagogical ergonomics offers advantages over other conceptual frameworks that investigate similar issues. For example, pedagogical ergonomics shares some assumptions of complexity theory and ecological frameworks, such as the emergent nature of classroom interaction. Nonetheless, complexity theory is often inappropriately adapted from the natural sciences to education in reductive and ‘formulaic’ ways, frequently overlooking political dynamics and human intention in education (Fenwick et al., 2015). Pedagogical ergonomics obviates such shortcomings by grounding itself in teaching practice in a particular sociocultural, political, and physical space. Additionally, while the pedagogical ergonomics concept of intra-action bears some similarity to the notion of affordance from ecological frameworks and sociocultural theory (SCT), pedagogical ergonomics focuses on what actually happens rather than on hypothetical opportunities for learning—the most common definition of ‘affordance’ (van Lier, 2008). Also unlike SCT, pedagogical ergonomics acknowledges ‘material agency,’ treating objects not as a secondary issue in the service of human cognitive development but as central to what happens in classrooms (see Canagarajah, 2018, on SCT versus complexity theory versus sociomaterialism).

‘Intra-action’—one of this study’s central contributions—conceptually focuses on happenings and eschews linguistics-centric epistemologies, similar to the construct of action. However, the explanatory power of intra-action goes beyond the concept of action, by centering on relata, activity, interaction, influences, engagements, and exchanges among entities and beings. The definition of intra-action in this article differs somewhat from that of a prominent sociomaterialist Barad (2007), whose view on ‘intra-action’—carried over from physics— disputes the existence of preconceived boundaries among agents. Barad’s (2007) unwieldy conceptualization of intra-action has been critiqued as inappropriate and impractical for social science research (Leonardi, 2013). Moreover, sociomaterialist scholars of education—namely, Fenwick et al. (2011)—have at times referenced intra-action somewhat vaguely. Consequentially, the present study fleshes out and redefines this construct for pedagogy research. Based on the impacts of related, narrower frameworks (e.g., cognitive ergonomics) in mathematics education (Choppin et al., 2018), the present study’s revised definition of intra-action and the pedagogical ergonomics framework in general may contribute not only to applied linguistics but to broader education research.

Another important aspect of pedagogical ergonomics is classroomscape, which various articles of this special issue depict without explicitly naming (Hasegawa, 2021; Kim & Canagarajah, 2021; Matsumoto, 2021). Their inclusion of classroomscape elements further highlights the construct’s utility for investigating materials use. While research into ‘schoolscape’ (e.g., Laihonen & Szabó, 2018) has surged, the construct ‘classroomscape’ is less recognized. Importantly, classroomscape is just one type of cultural and physical pedagogical space. While not all language learning occurs in Euro-Western-style classroomscapes like this FFL course, the broader and more flexible concept of ‘space’ is applicable to diverse pedagogical settings (e.g., Indigenous language learning in nature; [Engman & Hermes, 2021, this issue]).

Drawing on pedagogical ergonomics, this article builds on the definition of LLT materials use presented in this issue’s introduction (Guerrettaz et al., 2021). The present article aligns with that definition—acknowledging distributed agency and intra-action in materials use—while also exploring this construct in greater depth. In the current article, materials use was defined as class- room action involving influences, engagements, and exchanges among LLT materials, one or more learner, and often the teacher—situated in a physical, sociocultural, and political space. This definition of materials use is (a) more concrete than that of the introduction (Guerrettaz et al., 2021), (b) more focused on materials in classroom activity and interaction, and (c) not dependent on sociomaterialism. The present study’s definition can be understood and adapted by greater diversity of researchers and practitioners, including those unfamiliar with the specific theoretical orientation of the issue’s introduction.

A fundamental tenet of pedagogical ergonomics is the unity of research and practice (see Wilson, 2000). It can thus help advance applied linguistics, which has struggled in some circles to bridge the ‘theory–practice divide’— with linguists and researchers on the one side and language teachers on the other (e.g., Ellis, 2010; Freeman & Johnson, 1998; van Lier, 2008; Vodopija–Krstanovic´ & Marinac, 2019). Related to this, varied approaches, including observational and practitioner research, are arguably important to future pedagogical ergonomics inquiry. Moreover, my positionality in the present study was not only that of an ‘outside’ researcher but also of a long-time language teacher. This undoubtedly contributed to Edgar’s and my strong working relationship and my instinct to conduct action analyses—the study’s methodological innovation.

Regarding key findings with pedagogical implications, the modalities of materials use (i.e., communal, universal, distributed, and responsive; Table 3) capture foundational dynamics of many language classrooms’ modus operandi. This paradigm complements the typology of mate- rials in the special issue’s introductory article (Guerrettaz et al., 2021), which focuses on intrinsic qualities of materials-in-use (e.g., text, sign, technology, environment, and entity) rather than intra-actions among these and students. Importantly, no one modality or genre is necessarily superior to the others; their appropriateness and effectiveness depend on myriad considerations. The primary value of these modalities or genres is the shared terminology they offer the field for unpacking materials-use phenomena.

In this study, modalities of use and genres of materials went hand-in-hand, possibly because the teacher had designed the materials. Genre and modality of materials-in-action may coincide less when teachers use materials created by others. Future research might (a) investigate if and when genre and modality of use may diverge, and (b) reveal additional modalities and genres. As an ex- ample of the latter, evidence for ‘shared materials’ emerged in a focus group where focal participant Celine speculated, “If you had (. . .) one worksheet to two people it would make (. . .) [group work] more interactive” (6 October 2015). This exemplifies how “groups, texts, and tasks can be manipulated to increase participation, engagement, and (. . .) learning” (Doreen Ewert, personal communication, 11 June 2020). Additionally, the category ‘distributed materials’ invites refinement: Materi- als like extensive reading kits—books tailored to individual proficiency levels—may instead be conceptualized as ‘differentiated materials’ (see Ew- ert, 2017).

The practical utility of pedagogical ergonomics was also apparent in the present study when different ‘raw materials’ resulted in similar class- room outcomes. For example, the handout use (Excerpt 1) and a whiteboard usage (not described here) separately induced similar intra-actions: Both involved reduced (m)IRF chains, form-focused instruction, and the teacher plus the material in question as the loci of action. As another example of how pedagogical ergonomics can explain classrooms’ inner workings: The more complex activities—like the fractal mapping of student responses onto the fill-in-the-blank handout—did not promote the most L2 use by students. Rather, the simplest materials and task— describing images of houses—prompted the most meaning-focused student language production (Excerpt 2).

This research also has implications for language teacher development (Graves & Garton, 2019). Preservice educators especially may find the genres and modalities (i.e., universal, communal, distributed, and responsive) edifying. Moreover, novice and experienced teachers can independently conduct action analyses and diagrams for reflection and planning. Similarly, teacher education programs can incorporate pedagogical ergonomics, classroomscapes, and action analyses. Additionally, pedagogical ergonomics illuminates resonances across the sister areas of materials scholarship: design, evaluation, and use. Moreover, we language teachers might enhance our general pedagogical practice by taking intra-action as a starting point for planning and reflection. ‘Normative’ materials—like fill- the-blank texts (Figure 4)—dominate many class- rooms (Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2018). However, we teachers can instead prioritize desirable student–material intra-actions.

The pedagogical ergonomics framework and polysemiotic action analyses integrate aspects of teaching that sometimes appear disjointed, like classroom materials, language learning objectives, teaching methods and strategies, and student language. These and other reified constructs in language education research are at times disconnected from the tangible ‘happenings’ of language classrooms (see Cowley, 2012). Yet “learning (. . .) emerges in (. . .) [concrete] encounters with the world” (Cowley, 2012, p. to shift attention away from “the hypothetical [emphasis added] processes of language ‘learning’” (p. 3). Language education research must adapt to better reflect the ‘general project’ of language teaching practice, which is tangible action in the sociomaterial world.

Indeed, many approaches to language education research are rather abstracted from moment-to-moment classroom realities (Cowley, 2012). In contrast, these realities are the focus of pedagogical ergonomics, which uniquely integrates research, theory, and practice, with potential to advance the much needed area of materials-use inquiry in particular. As with other areas of ergonomics study, language teaching is simultaneously art, craft, and engineering of the cognitive, social, and material dynamics of classrooms (following Wilson, 2000), which the pedagogical ergonomics framework seeks to understand and address.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First and foremost, I thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback. Also, I extend deeply heartfelt thanks to: a) the teacher and student participants who made this research possible, and b) Kathleen Graves and Mel M. Engman for their extremely generous and insightful feedback on earlier versions of this article. I am grateful to Elaine Tarone, Brian Tomlin- son, Hitomi Masuhara, MUSE International members, and MATSDA 2019 conference attendees for their input on various aspects of this research. Additionally, I thank Amy Roth-McDuffie and Cory Mathieu for intro- ducing me to curriculum ergonomics and mathematics education ‘materials-use’ literature. Also, I thank Brian French, Nicole Ferry, and Tyson Koepke for their assistance and support. Finally, thank you to Tara Zahler, Doreen Ewert, and Bill Johnston for helping me grow as a pedagogue.

注:本文选自The Modern Language Journal, 105 (2021) 39–64。由于篇幅所限,注释和参考文献已省略。